10 ways SLAC’s X-ray laser has transformed science

In the decade since LCLS produced its first light, it has pushed boundaries in countless areas of discovery.

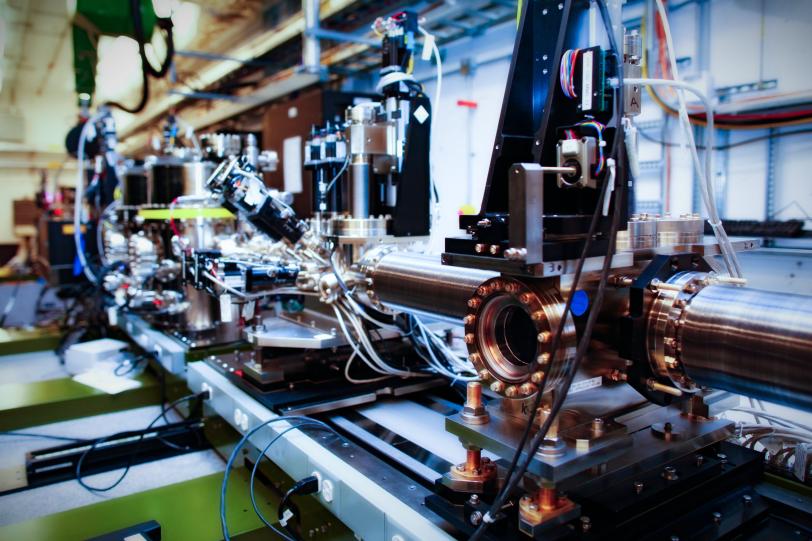

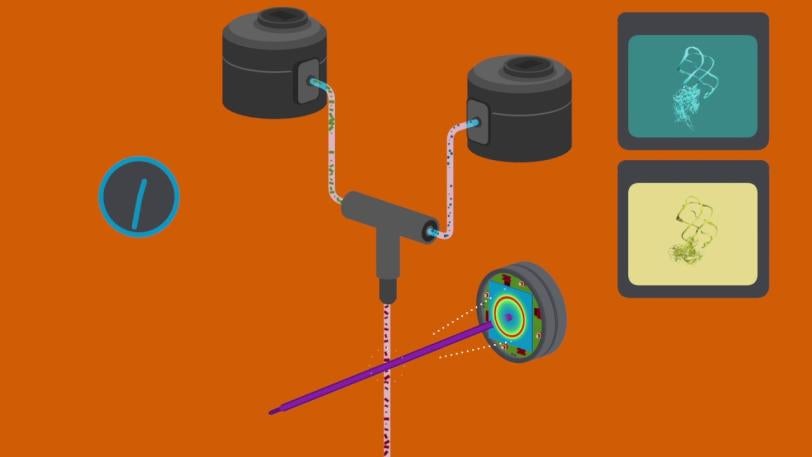

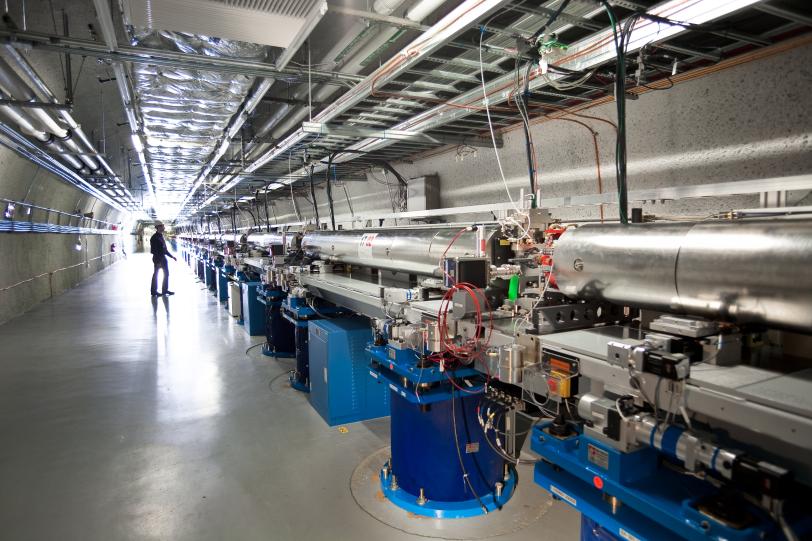

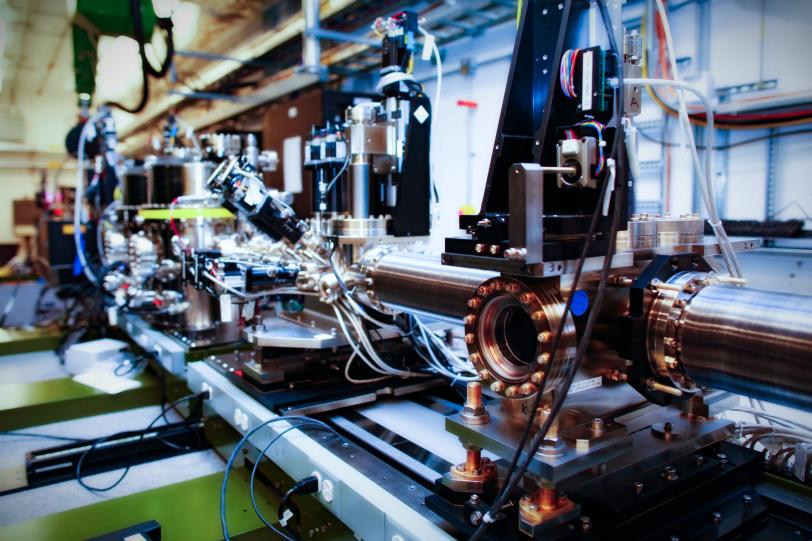

When scientists at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory took on the task of building the world’s very first X-ray laser capable of imaging matter at the atomic scale, they knew they were in for an uphill battle. The Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) was designed to generate X-ray pulses a billion times brighter than anything that had come before. It would be the first machine to produce high energy (or “hard”) X-ray laser pulses that would last for just femtoseconds, millionths of a billionth of a second.

If successful, LCLS would enable new science at ultrasmall, ultrafast scales. It would be a new tool, a “microscope” that could spy on the intricate movements of atoms and molecules, capturing their motion in freeze-frame “movies.” It would deepen our fundamental understanding of the building blocks of life and position scientists to make advancements in areas ranging from clean energy to next-generation computing and improved medicines.

In order to work, LCLS would need a tremendous leap in cutting-edge technologies, requiring scientists, engineers and technicians from around the world to pool their expertise and clear uncountable hurdles. Many thought it was a leap too far, requiring a precision that was simply not practical.

But the U.S. Department of Energy decided the scientific reward was great enough to take the risk, and invested almost half a billion dollars for the LCLS project. A team was formed that pulled together researchers from SLAC, Argonne, Lawrence Livermore, Los Alamos and Brookhaven national laboratories, along with the University of California, Los Angeles and many other institutions from around the world.

In April 2009, after more than a decade of painstaking effort, the lab made history when a tiny bunch of electrons completed a nearly speed-of-light journey through the kilometer-long accelerator to produce the very first burst of X-rays from an exquisitely aligned series of magnets: the first light from LCLS.

Since that moment, SLAC has been the birthplace of a host of scientific firsts. Here are 10 areas where LCLS has shined new light in the 10 years since it turned on.

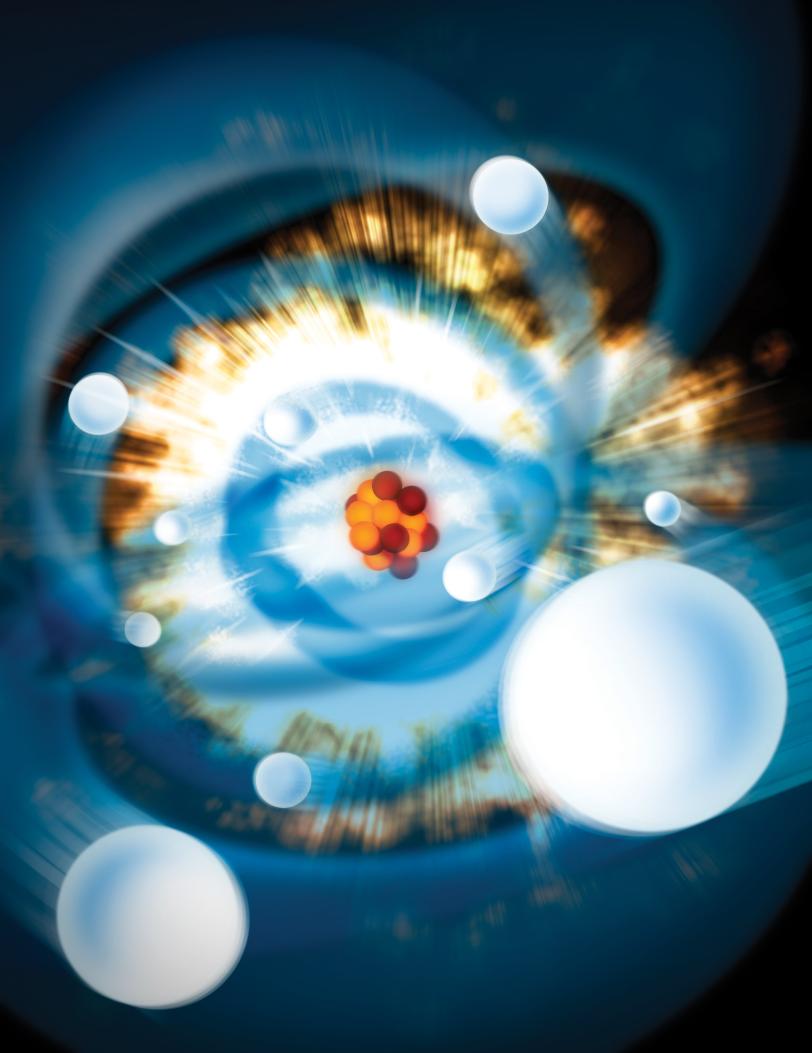

1. Unpeeling atoms and molecules from the inside out

LCLS can produce X-ray pulses about 100 times more intense than all the sunlight hitting the Earth’s surface focused onto a thumbnail. These extreme pulses provide a revolutionary path forward for imaging man-made nanomachines and individual biological objects, such as proteins and other macromolecular complexes, at high resolution.

But that powerful beam also does a lot of damage, so a wholly new type of measurement had to be developed to take advantage of this new source of light. This method, called diffract-before-destroy, is one of the keys to LCLS’s success, allowing researchers to collect precise information from delicate samples in the instant before they’re blown apart.

Some of the first studies at LCLS took advantage of this unprecedented intensity. They showed that the brilliant laser light can strip electrons away from atoms from the inside out, creating “hollow atoms.” Many new aspects of the ionization of atoms were revealed for the first time, including the importance of transient phenomena, which informed the development of a more advanced theory of atomic physics.

Understanding this fundamental interaction of matter and light is essential for recreating the wild conditions needed to produce new states of matter, and for warding off damage in samples researchers are trying to image.

Ring-shaped molecules are a bedrock of biochemistry, such as the processes that lead to the formation of vitamin D, and lie at the heart of many pharmaceutical compounds and the synthesis of new types of materials. With LCLS, researchers were able to track, for the first time, the ultrafast movements of these molecules as they burst open and unfurled.

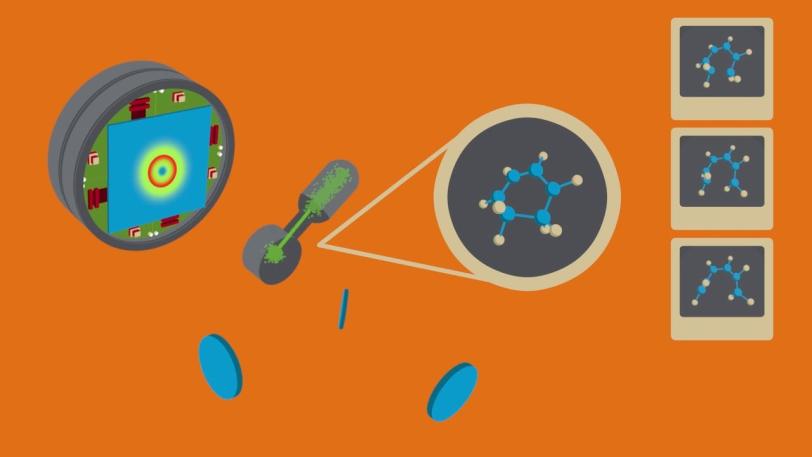

2. Recording molecular movies of chemistry in action

Ring-shaped molecules are a bedrock of biochemistry, such as the processes that lead to the formation of vitamin D, and lie at the heart of many pharmaceutical compounds and the synthesis of new types of materials. With LCLS, researchers were able to track, for the first time, the ultrafast movements of these molecules as they burst open and unfurled.

XPP | New ‘Molecular Movie’ Reveals Ultrafast Chemistry in Motion

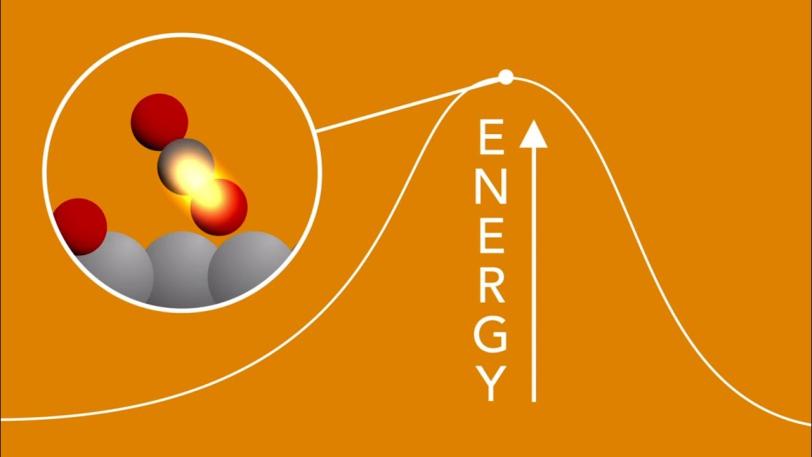

The fact that the X-rays from LCLS arrive in a burst just a few femtoseconds long lets us generate a stop-motion “molecular movie” that reveals how the shape of the molecule changes throughout the reaction. Compared to other approaches, the extreme brightness and short pulse duration of LCLS provided measurements that were almost completely free of background noise, allowing clear interpretation of the molecular structures and the role of electrons in driving the reactions.

This ability to directly image the motion of atoms as they undergo a chemical reaction represents a step change in our capacity to link the structure of molecules with how they function and react, and it allows us to develop improved approaches to understanding and controlling complex material synthesis.

3. Watching molecules “breathe”

In a milestone for studying a class of chemical reactions relevant to novel solar cells and memory storage devices, scientists used LCLS to watch “molecular breathing” – waves of subtle in-and-out atomic motions – in real time and unprecedented detail.

These ripples of motion revealed how energy is exchanged between light and electrons. Researchers tracked how the energy led to tension and eventually motion of atoms in an iron-based molecule that’s a model for transforming light to electric energy, showing future potential for creating a switchable molecular memory device.

To see it “breathe,” the molecule was hit by a burst of laser light, immediately followed up with an X-ray pulse from LCLS to examine the changes that took place. The laser light excited an electron in the central iron atom of a molecule, which was then transferred to an outer wing of the molecule. When the electron returned to the iron atom 100 femtoseconds later, it flipped the magnetism of the iron. This caused the molecule to expand, setting off a breath-like oscillation through the entire structure.

4. Catching the birth of chemical bonds

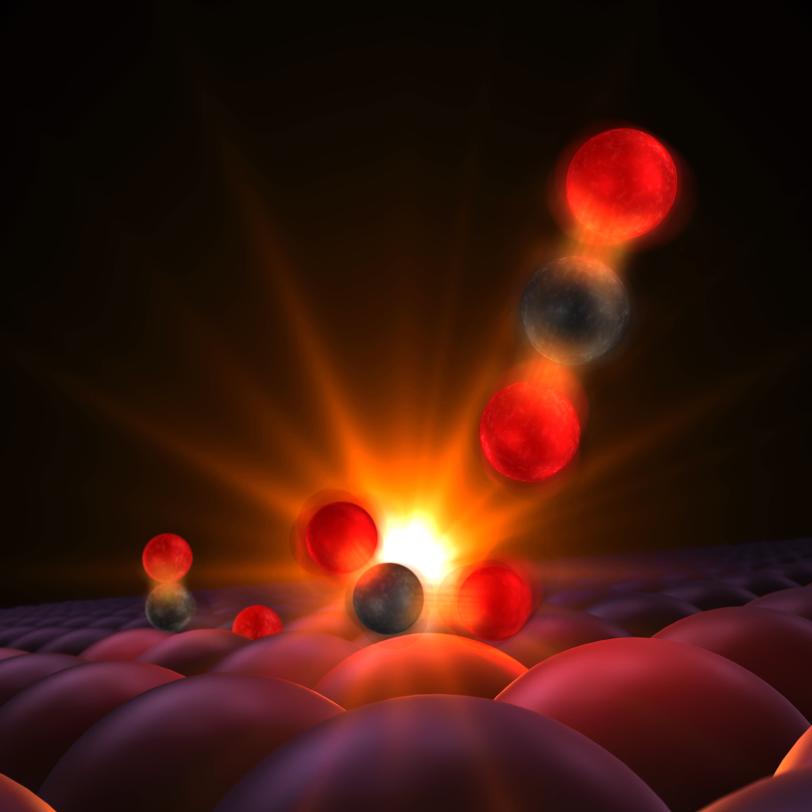

The acceleration of chemical reactions, a process called “catalysis,” underpins a vast number of industrial processes, such as the production of fertilizer, but we lack a fundamental understanding of the chemical bond formation that underpins this and many other areas. LCLS’s laser pulses are so short that they can capture snapshots of reactions as they unfold, illuminating previously hidden steps at the atomic scale.

In one study, researchers watched in real time as a chemical bond formed between atoms on the surface of a catalyzing metal plate. They were able to follow, at the femtosecond timescale, subtle changes in the motions of carbon and oxygen atoms on a ruthenium surface when illuminated by laser light, and reveal the fleeting transition states that can lead to the formation of carbon dioxide.

SXR | Scientists Get First Glimpse of a Chemical Bond Being Born

Understanding chemical reactivity is also important for the development of solar energy conversion, where there is a need to develop new techniques for mapping subtle changes in the underlying photochemical processes. Femtosecond LCLS pulses and their ability to probe specific atoms in a complex molecule were used to resolve a long-standing uncertainty in a benchmark photochemical reaction. These techniques can be broadly applied in many areas of chemical sciences, and are a driving reason for the high repetition rate of LCLS-II.

5. Cracking the mysteries of photosynthesis

Despite its crucial role in creating and sustaining life on Earth, photosynthesis is still not fully understood. One of its best kept secrets is how photosystem II, a key protein complex in nature, harvests energy from sunlight and uses it to split water and produce the oxygen we breathe. A better understanding of how this process works could provide a blueprint for developing clean sources of renewable energy.

Until recently, it had only been possible to measure fragments of this process at extremely low temperatures. At LCLS, scientists can study and image steps of the process at its natural temperature, mapping both its structure and chemistry before the sample is destroyed. The ultrafast pulses of X-rays are used to produce two sets of data: X-ray crystallography data, a map of the molecular structure with atomic resolution, and spectroscopy data, a map of how electrons flow in the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II. This approach allowed the researchers to narrow down the proposed mechanisms put forward by the research community over the years.

Details of Photosynthesis Captured by SLAC’s X-ray Laser

Most recently, they were able to track the position of the oxygen atoms and the heavier metal atoms in the molecule, capturing all four metastable states of the process as well as some fleeting steps in between, providing unprecedented insight into the mysteries of photosystem II.

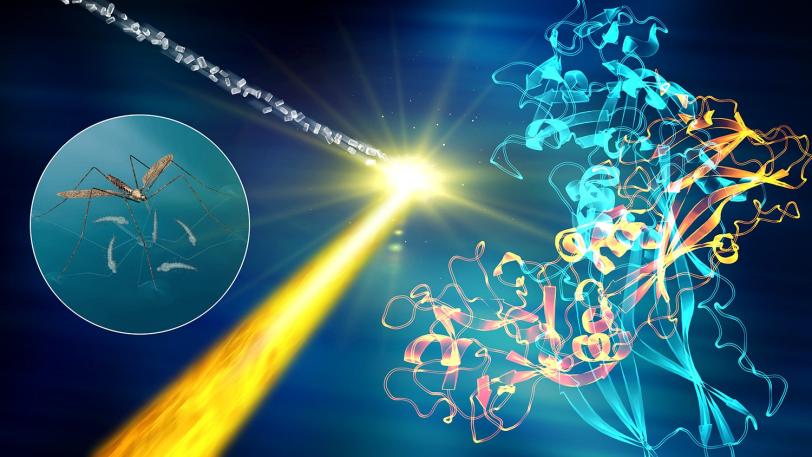

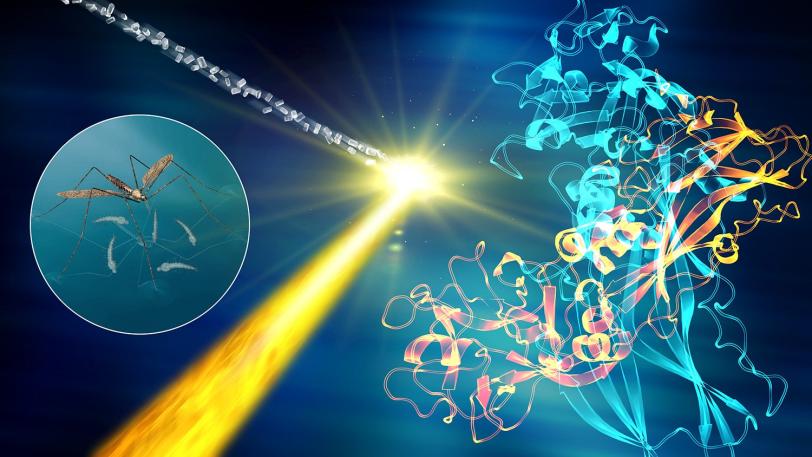

6. Mapping drug targets in motion

To accelerate the design of more effective drugs with fewer side effects, researchers need to map how drugs dock with their protein targets in the cell with atomic resolution. The best way to do this is to crystallize the drug as it binds to a protein, but it’s sometimes difficult to grow crystals that are large enough for structural studies using conventional X-ray crystallography.

LCLS offers researchers a way to get data from much tinier crystals in ambient conditions, allowing faster, more accurate imaging of hard-to-study drug targets. LCLS has pioneered powerful new experimental methods – diffract-before-destroy and serial femtosecond crystallography – that have opened new areas of structural biology by enabling high-resolution, damage-free 3D structures of membrane proteins, metalloenzymes and small bio-crystals in near-native environments.

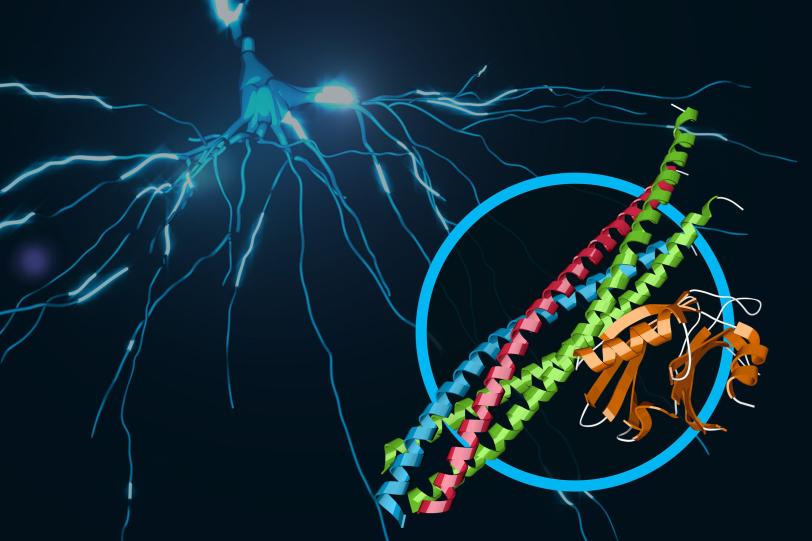

In an ongoing series of experiments, researchers are mapping the structure of G-protein coupled receptors that play a key role in controlling signaling in our cells, and which are targeted by a very large number of pharmaceutical drugs on the market.

Recent experiments in this series have revealed how a hypertension drug binds with a target (angiotensin-II) that helps regulate blood pressure, and provided key structural details for a cell signaling pathway in the human body (rhodopsin-arrestin) that regulates sensory and hormonal responses. Other experiments studied the atom-by-atom details of brain signaling to help underpin our understanding of neurological diseases and determined the structure of a larvicide to aid the battle against mosquito-borne illnesses such as Zika and dengue fever.

XPP | Unlocking the Secrets of Brain Signals

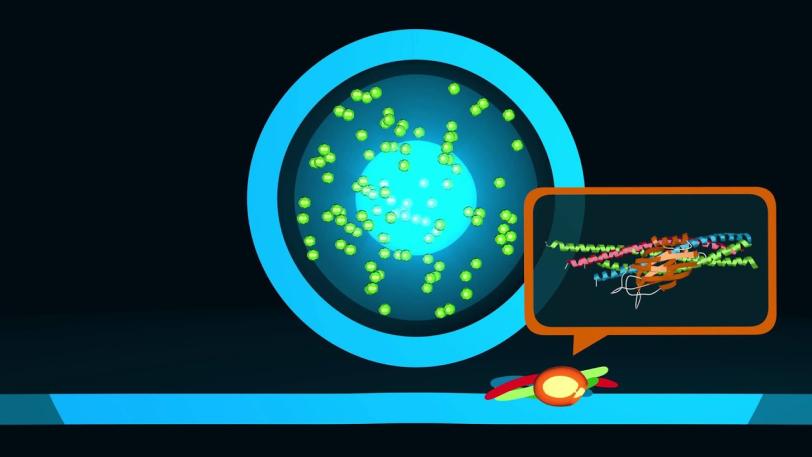

7. Uncovering the mechanics of biological machines

Every human is powered by a vast array of proteins and other biological machines that guide everything from how we see to how the body responds to viruses. For decades, biological function has been inferred from static maps of the 3D structure of crystallized molecules. But functioning biological systems are not static. To gain a deeper understanding, it’s important to study how the structures change over time, often as a result of external stimuli such as a change in environment.

With LCLS, researchers can now capture atomic-resolution snapshots of biological structures as they evolve over time. In one landmark experiment led by the National Institutes of Health, the dynamics of riboswitches, which are elements of messenger RNA central to genetic regulation, were mapped during a reaction initiated by the arrival of an external molecule. This resulted in a large change in the molecule’s shape, revealing at least four transient states and illustrating how the structure of the molecule is linked to the way signals are transmitted. More generally, these results opened up a new form of measurement for studying biochemically important interactions between bio-macromolecules and ligands.

CXI | X-ray Laser Gets First Real-time Snapshots of a Chemical Flipping a Biological Switch

In other work, LCLS was used to make the first molecular movie of the moment light hits retinal, a sensor that’s central to a number of important light-driven processes in animals, microbes and algae, including vision and photosynthesis. This and other results give scientists an early glimpse into how X-ray molecular movies are likely to transform our understanding of the natural world.

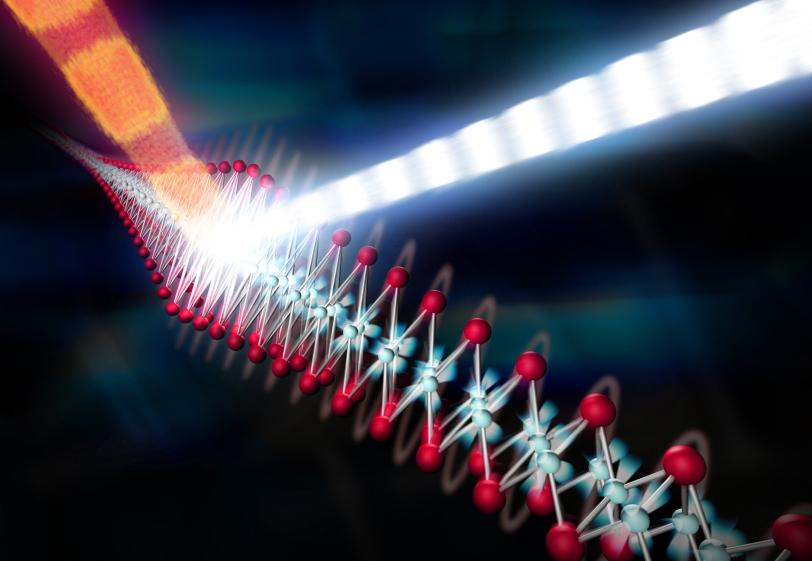

8. Chasing room-temperature superconductivity

Superconductors, materials that conduct electricity with 100 percent efficiency, operate only at extremely cold temperatures. Even so-called high-temperature superconductors have to be chilled to at least minus 73 degrees Celsius with liquid nitrogen, and this greatly limits their usefulness. Scientists have tried for decades to create superconducting materials that work at close to room temperature, which could enable lossless electrical transmission and fast maglev trains.

Particularly puzzling is the behavior of superconductors containing iron, where it has proven very difficult to calculate or measure the strength of the interactions between the electrons and ions, and thus determine the interactions that can lead to the emergence of superconductivity. In a tour de force experiment, researchers combined LCLS and laboratory data to measure this interaction directly, without having to rely on any theoretical models. The material was struck by a light pulse to set it “ringing” at a characteristic frequency, which was then measured with atomic precision by the X-ray pulses. The results showed a much stronger coupling between the electrons and ions than conventional theories would predict, providing important insight into the role of the interplay between electrons and ions in these materials.

Along with a wide array of related experiments, these studies are greatly increasing our understanding of the complex world of quantum information science and opening new avenues for harnessing the esoteric effects of quantum mechanics in our everyday lives.

9. Harnessing magnetism and electronic behavior

The ability to control the magnetism and electronic behavior of materials more precisely will enable scientists to design next-generation smartphones and computers that are faster, smaller and much more efficient. One approach involves the study of a class of materials known as multiferroics, in which electric fields can control magnetic behavior and vice versa. The ultimate speed at which the behavior can be controlled, however, remains largely unknown.

At LCLS, researchers used pulses of specially tuned light to change the magnetic properties of a multiferroic material, and then used the ultrafast X-ray pulses to show that the atomic-scale magnetic structure can be directly manipulated in less than a trillionth of a second. This gives researchers new insight on how to write data with light, creating a pathway to much faster data storage.

The substantial increase in power provided by LCLS-II will give us an unprecedented ability to probe the interaction of light with complex materials, opening up the development of a new generation of electronic devices with novel functional properties.

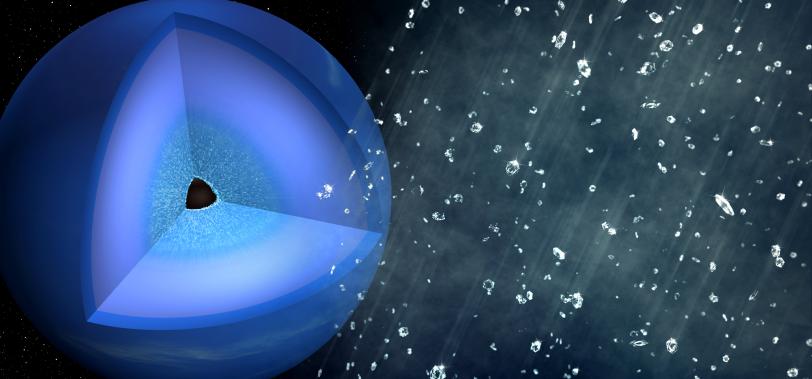

10. Probing materials in extreme environments

Using high-power lasers, scientists can create 36-million-degree matter – almost 10 million degrees hotter than the sun’s core – that mimics the harsh conditions found in many astrophysical objects, and also create pressures equivalent to 5,000 large African elephants stacked on 1 square inch of ground.

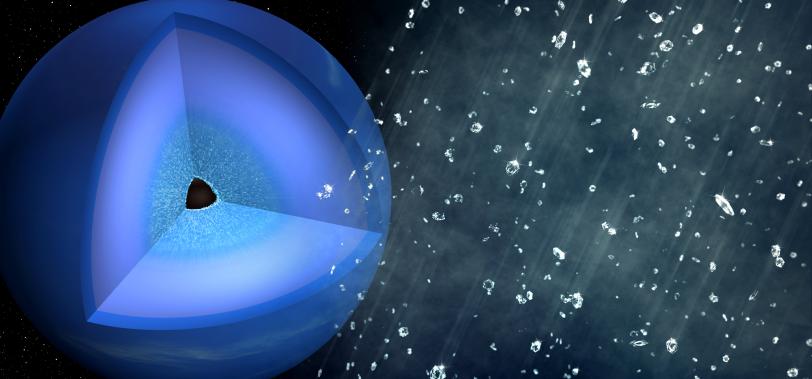

Scientists use LCLS’s femtosecond X-ray pulses to measure how matter responds to these extreme conditions. For example, they are able to re-create the exotic chemistry that occurs at the center of planets to help us understand the spectacular array of exoplanets now observed around other stars. Recent LCLS experiments investigated the atomic-scale dynamics of hydrocarbons under conditions comparable to those 10,000 kilometers below the surface of Neptune. Ultrafast X-ray measurements revealed a separation of carbon and hydrogen from the bonds of the polymer chain molecules, and the subsequent formation of nanodiamonds. These results demonstrate that both high temperatures and high pressures are needed to initiate the carbon-hydrogen separation, and imply that “diamond rain” requires approximately 10 times higher pressure than indicated by previous static experiments.

By mimicking in the lab some of the most violent environments in the universe, scientists are developing a deeper understanding of a wide range of astrophysical processes and learning how to create new kinds of materials.

Leveling up: The next 10 years

Although LCLS has made great strides in many areas of science, there’s still more to be done. When LCLS-II, a superconducting X-ray laser that will run alongside LCLS, comes online, it will bump X-ray science to new heights. The beam will be an average of 10,000 times brighter and fire 8,000 times faster than the original, producing up to a million pulses per second and enabling further advancements in materials, physical, chemical and biological sciences.

And just as with LCLS, many of the ways it will transform the world will remain unseen until after first light.

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.