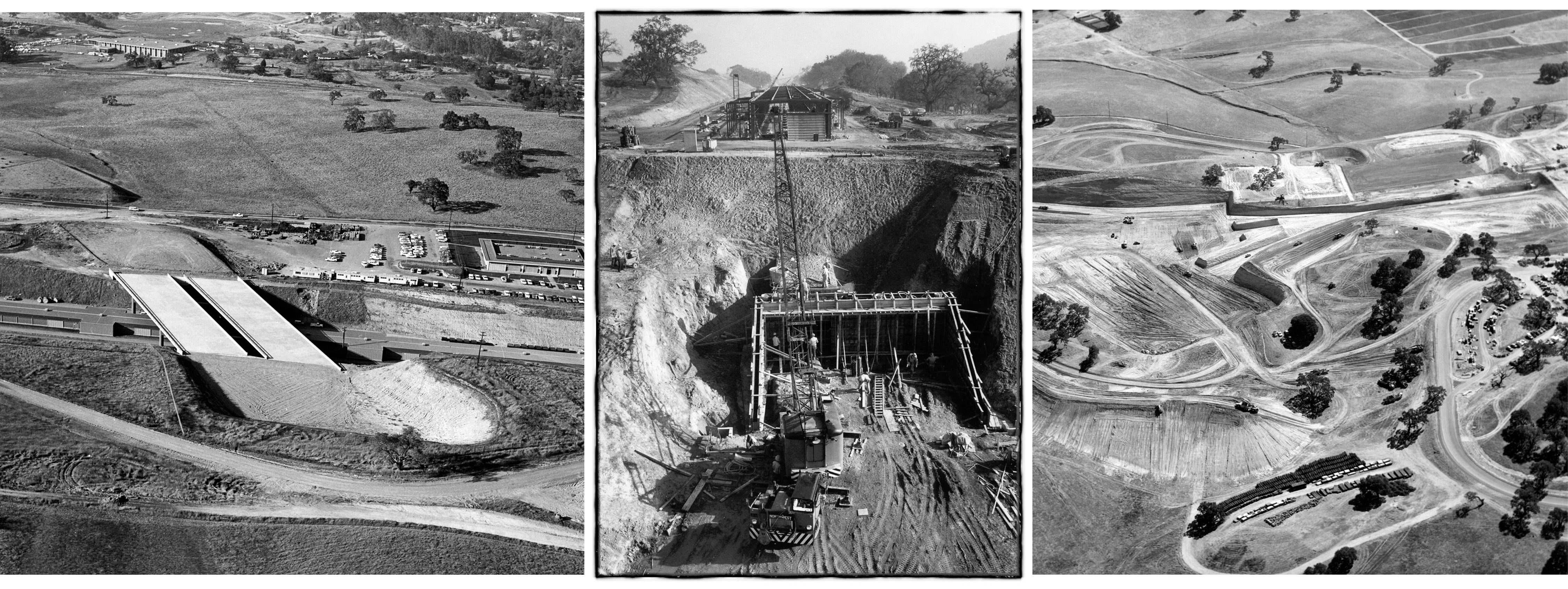

In 1962, in the rolling hills west of Stanford University, construction began on the longest and straightest structure in the world. The linear particle accelerator – first dubbed Project M and affectionately known as "the Monster" to the scientists who conjured it – would accelerate electrons to nearly the speed of light for groundbreaking experiments in creating, identifying and studying subatomic particles.

SLAC would go on to become a multi-program lab and a world leader in X-ray and ultrafast science, diversifying its scientific mission to include cosmology and astrophysics, materials and environmental sciences, biology, sustainable chemistry and energy research, scientific computing and more.

SLAC Archives, History & Records Office

For detailed historical information, history bits SLACspeak (including our many acronyms),interviews and more, please visit the SLAC Archives, History & Records Office (AHRO) website.

History posts

SLAC celebrated its 60th anniversary. See our history posts on instagram.

For more, visit the SLAC turns 60 site.

The founding of SLAC

Stanford University leased land to the federal government for construction of the new Stanford Linear Accelerator Center and provided the brainpower for the project. This set the stage for a productive and unique scientific partnership that continues today, made possible by the sustained support and oversight of the U.S. Department of Energy.

SLAC’s Nobel Prizes

Four Nobel prizes have been awarded to six scientists for research at SLAC that discovered two fundamental particles, proved protons are made of quarks and showed how DNA directs protein manufacturing in cells.

The hunting of the quarks

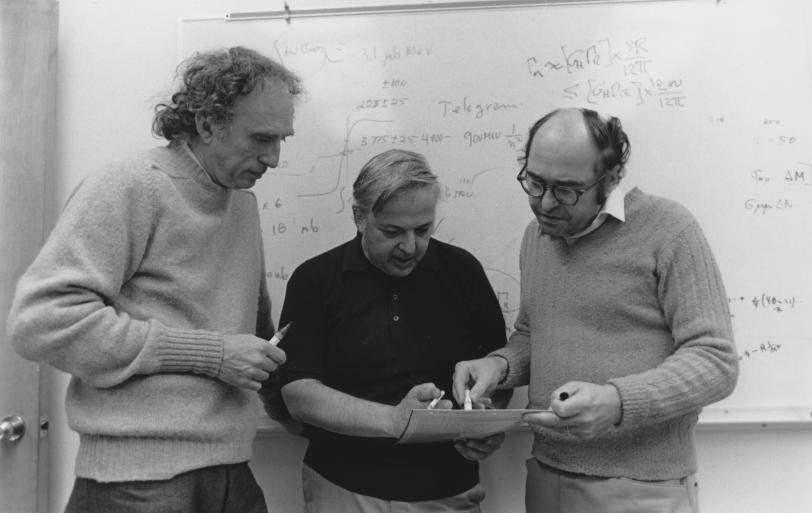

Scientists have known since the 1930s that an atom’s nucleus contains protons and neutrons. But were these made of even smaller particles? Some theorists thought so; but by the late 1960s no trace of these theoretical building blocks, whimsically named quarks, had been found.

In 1967, a team of SLAC and MIT scientists began using electron beams with record high energies from the 2-mile-long SLAC linear accelerator to probe the nuclei of hydrogen and deuterium atoms. At first they saw nothing unusual. But when they switched to a technique called “inelastic scattering,” they were surprised to see electrons scattering off “hard grains” in the centers of protons and neutrons. Those hard grains were the up and down quarks that theorists had predicted years before.

In 1990 the Nobel Prize in physics was awarded to the leaders of the experiments – Richard E. Taylor of SLAC and Stanford and Jerome I. Friedman and Henry W. Kendall of MIT.

The electron’s heavy cousin

When SLAC’s 2-mile-long linear accelerator turned on in 1962, scientists had identified two families of fundamental particles that each contained two leptons, including the familiar electron that orbits the nucleus of atoms.

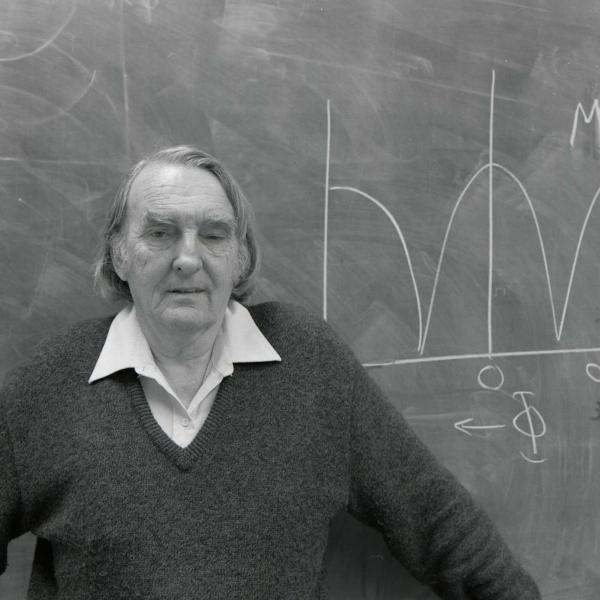

There was no reason to think a third family of particles existed. But SLAC’s Martin Perl wondered: Why not?

He immediately started searching for a third family at the new accelerator. When the powerful SPEAR collider became available in 1973, he began looking there, too, in the debris from electron-positron collisions.

In 1975, after years of persistent trying in the face of widespread skepticism, Perl discovered the first member of the third particle family – the tau lepton, which is 3,500 times more massive than its cousin, the electron. In 1995 he shared the Nobel Prize in physics.

The discovery inspired other scientists to go looking for two quarks and a neutrino to round out the third particle family. By 2000 they discovered all three.

The fourth quark is a charm

On November 11, 1974, two rival scientific teams announced that they had independently discovered the same particle at two of the world’s most powerful accelerators.

SLAC’s Burton Richter and his colleagues found it by colliding electrons and their antimatter opposites, positrons, in the lab’s SPEAR ring. They named the new particle “psi.” Samuel C.C. Ting’s MIT team found it by smashing protons into a beryllium target at Brookhaven National Laboratory. They named the new particle “J.” Scientists eventually agreed to call it J/psi.

Why was J/psi such a big deal? Because it’s made up of a charm quark and its antimatter opposite, anti-charm – and its discovery was the first demonstration that the charm quark actually existed. Charm was the fourth of the six known quarks to be discovered.

For their photo-finish discoveries, Richter and Ting shared the 1976 Nobel Prize in physics.

Translating life’s code into action

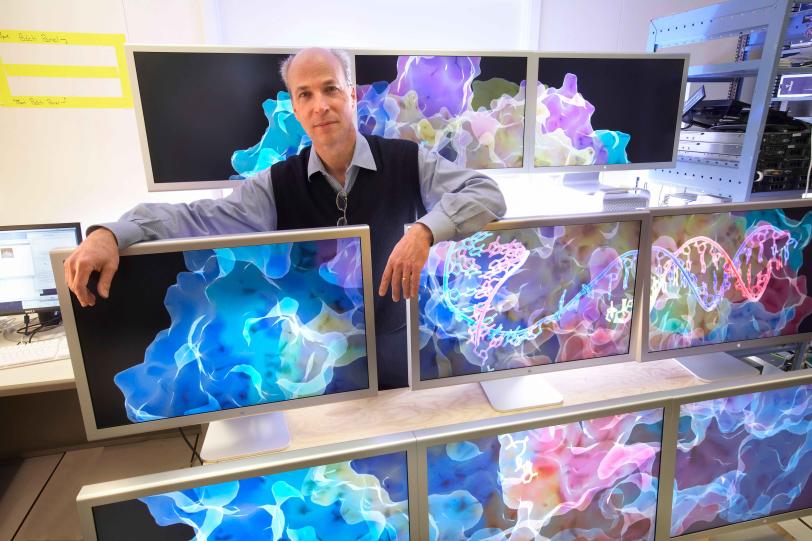

The instructions contained in our DNA would be useless without a way to carry them out. The first step in doing that is transcription. It copies the genetic instructions in DNA onto messenger RNA, which ferries them to the cellular factories where proteins are made.

Many illnesses are linked to hitches in transcription, and an interruption in this process can be fatal.

Roger Kornberg began studying the cell’s transcription apparatus in the 1970s. By 2001 his team at Stanford University School of Medicine had crystallized all the complicated molecules involved and probed their structures with X-rays at SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource and similar facilities.

They created the first complete picture of transcription in action for cells that have nuclei, like those found in mammals and yeast. It’s so detailed that you can distinguish individual atoms, making it possible to understand how transcription works and how it is regulated. For this work, Kornberg received the 2006 Nobel Prize in chemistry.

Exploring our past

Explore how SLAC’s scientific mission evolved to include cosmology, materials and environmental sciences, biology, sustainable chemistry and energy research, scientific computing and more through photos, articles and interviews. Learn more about our science and facilities of today and tomorrow.

Image gallery

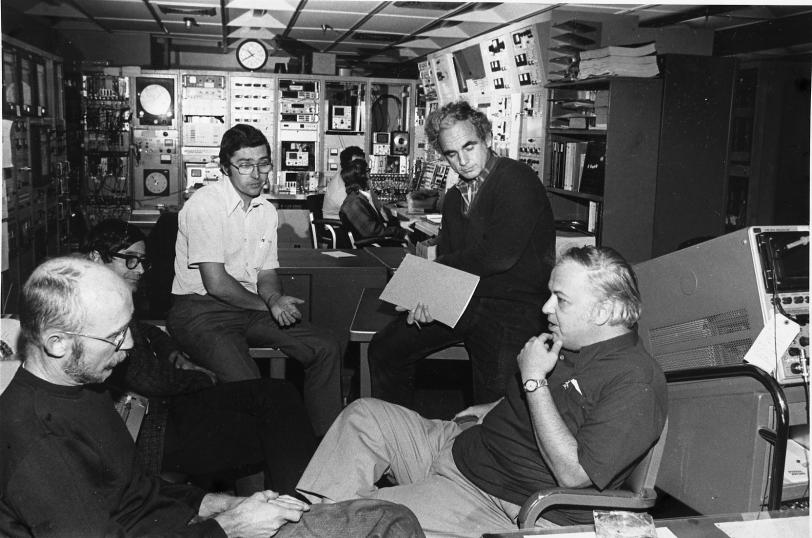

SLAC dedication day, 1967

SLAC's Minority & Women's committee, 1975

Theory Group's "Think Tank", 2003

Sarah Church, Stefan Funk, and Roger Blandford

Press conference - Martin Perl awarded Nobel Prize

Adeyemi Adesanya and Alf Wachsmann

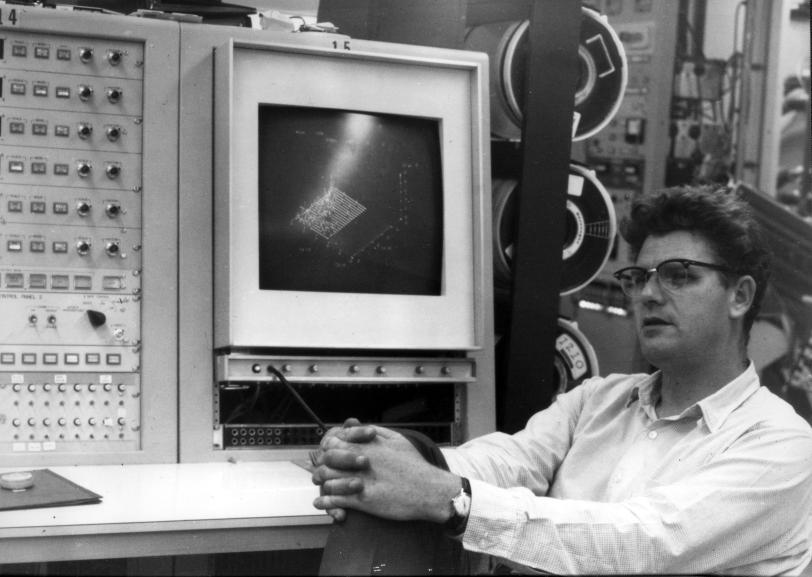

The age of colliders

In SLAC’s initial experiments, accelerated electrons were fired into stationary targets. Colliders allowed scientists to smash electrons and positrons into each other head-on at the much higher energies needed to reshape our understanding of matter.

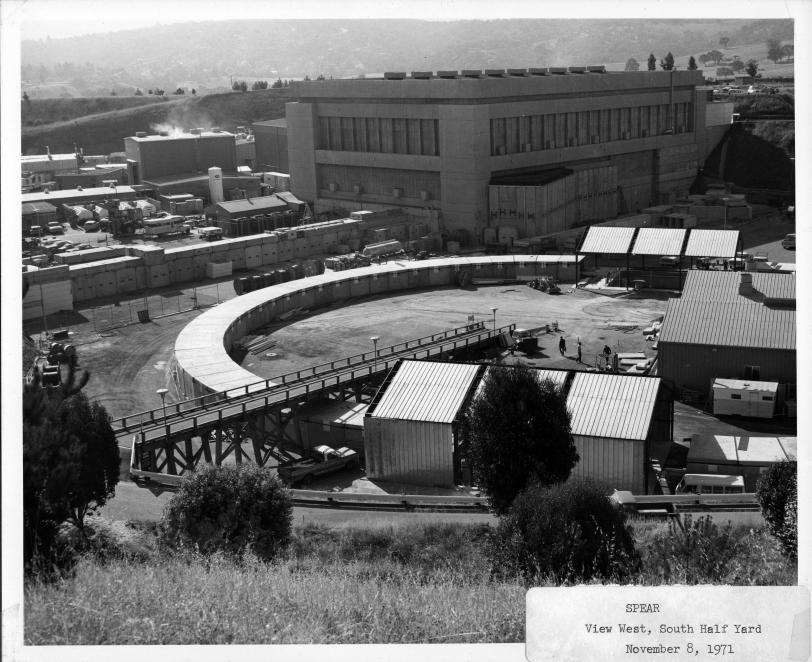

The Stanford Positron Electron Asymmetric Ring (SPEAR), completed in 1972, was the lab’s first collider - a ring 80 meters in diameter where accelerated electrons and positrons could be brought into collision at unprecedented energies. This allowed scientists to discover three fundamental particles that were the basis of Nobel prizes.

The Positron-Electron Project (PEP), a collider ring with a diameter almost 10 times larger than SPEAR, ran from 1980-90. The Stanford Linear Collider (SLC), completed in 1987, allowed scientists to focus electron and positron beams from the original linear accelerator into micron-sized spots for collisions. The SLC hosted a decade of seminal experiments.

PEP-II, the follow-on to PEP, included a set of two storage rings and operated from 1998-2008.

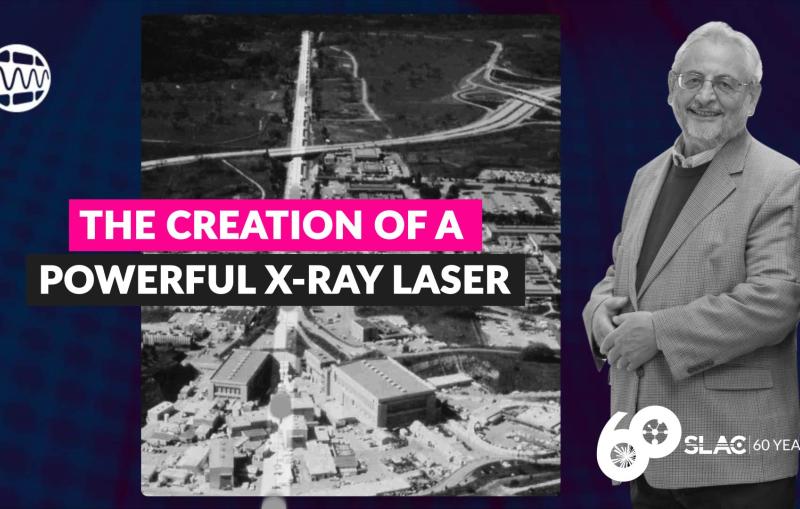

Synchrotron research and an X-ray laser

The Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Project, which opened to visiting researchers in 1974, used electromagnetic radiation generated by particles circling in SPEAR to explore samples at a molecular scale. Its modernized descendant, the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), now supports 30 experimental stations and about 2,000 visiting researchers a year. SPEAR, now known as SPEAR3 following a series of upgrades, became dedicated to SSRL operations in 1992.

Roger D. Kornberg, professor of structural biology at Stanford, received the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 2006 for work detailing how the genetic code in DNA is read and converted into a message that directs protein synthesis. Key aspects of that research were carried out at SSRL.

Meanwhile, sections of the linear accelerator that defined the lab and its mission in its formative years are still driving electron beams today as the high-energy backbone of two cutting-edge facilities: the world's first hard X-ray free-electron laser, the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), which began operating in 2009, and FACET-II, a test bed for next-generation accelerator technologies.

A changing mission

SLAC's scientific mission has diversified from an original focus on particle physics and accelerator science to include cosmology, materials and environmental sciences, biology, sustainable chemistry and energy research, scientific computing and more. The lab is also a world leader in X-ray and ultrafast science.

Scientists still come by the thousands to use lab facilities for an even broader spectrum of experiments, from archaeology to drug development, industrial applications and even the analysis of dinosaur fossils and art objects. Much of this diversity in world-class experiments is based on continuing modernizations at SSRL and the unique capabilities of LCLS.

Our global reach

Today our research truly has a global reach.

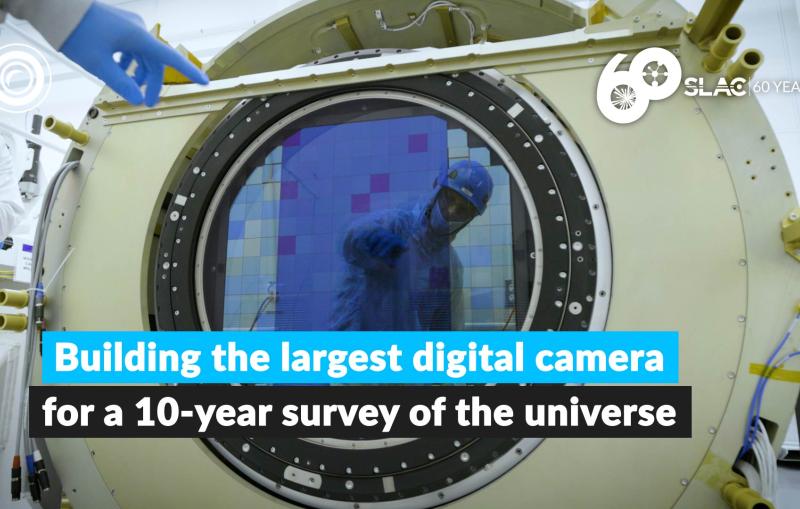

Our experimental footprint stretches from Latin America to Europe to the South Pole, from a Canadian nickel mine 6,800 feet below ground to a space telescope orbiting 300 miles overhead. We’re building the world’s biggest camera for ground-based astronomy; looking for patterns left by cosmic inflation in the first trillionth of a trillionth of a trillionth of a second after the Big Bang; and playing a leading role in searches for dark matter, dark energy and fundamental particles, whose discovery could poke holes in the Standard Model that describes all the known particles and forces.

By advancing the understanding of how nature and technology work at the largest, smallest and most fundamental levels and learning how to manipulate and control matter at the scale of atoms and electrons, we’re laying the foundation for both scientific impact and practical innovations.

Past directors

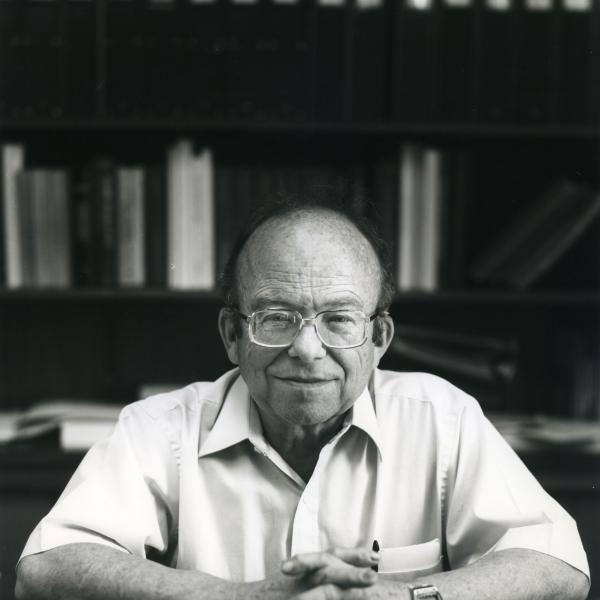

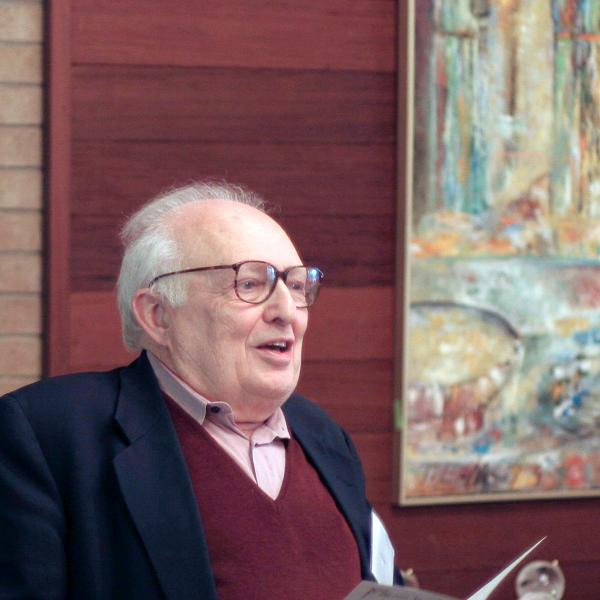

Wolfgang (Pief) K. H. Panofsky

Wolfgang K. H. “Pief” Panofsky, a renowned physicist and passionate arms control advocate, was SLAC’s first director. Panofsky pressed the case for basic accelerator research and the construction of new high energy physics facilities and promoted the use of SPEAR...

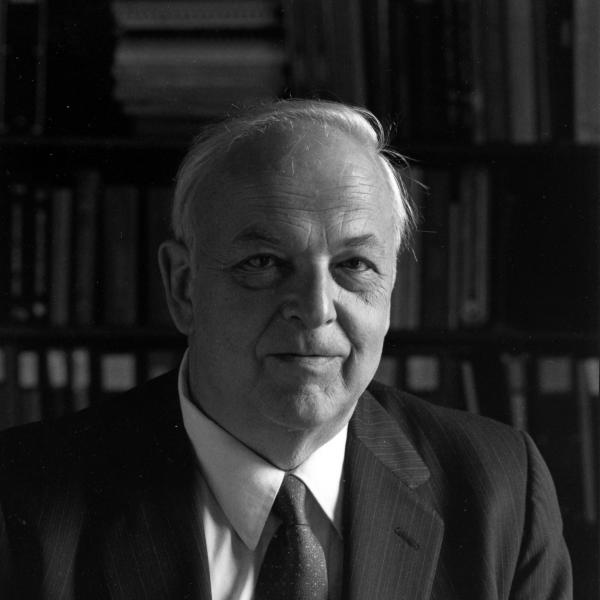

Burton Richter

The burst of scientific activity that began with the discovery of the J/psi particle in 1974 is known to particle physicists as the “November revolution” because it so radically changed their perspective. Burton Richter made that revolution possible by designing...

Jonathan Dorfan

An internationally recognized physicist, Jonathan Dorfan spent the first three decades of his career at the lab, where he led the design of the B-factory and helped bring together the 10-nation BaBar collaboration, among other accomplishments.

Persis S. Drell

In her early years at SLAC, Persis Drell worked on the construction of the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. She became SLAC’s deputy director in 2005 and was named director two years later. Drell is credited with helping broaden the focus...

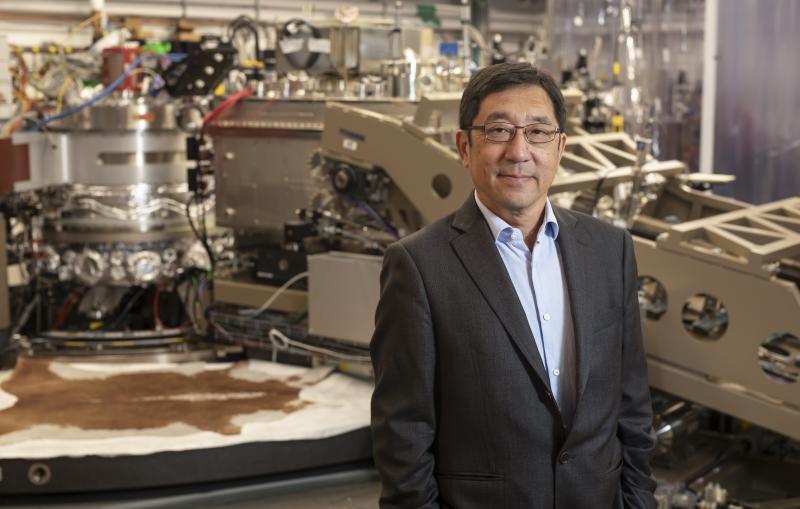

Chi-Chang Kao

Chi-Chang Kao, a noted X-ray scientist, came to SLAC in 2010 to serve as associate laboratory director for the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource. He became SLAC’s fifth director in November 2012. Previously, Kao served for five years as chairperson of...

Past deputy directors

Matthew Sands

Matthew Sands was instrumental in the construction and early operation of the laboratory. He helped design the SPEAR storage ring and wrote a monograph on electron storage rings. Sands was the first to demonstrate the importance of quantum effects in...

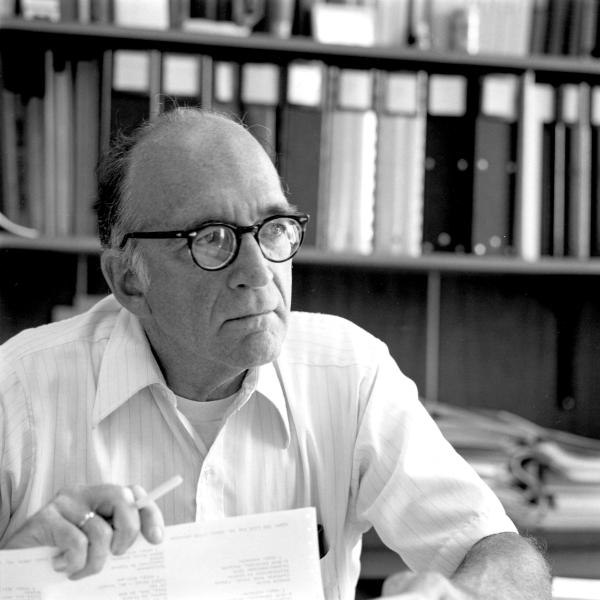

Gregory A. Loew

Gregory Loew spent his entire 50-year career at SLAC, starting in 1958 when it was still called “Project M.” He developed the design of the accelerator structure and many other microwave systems for SLAC’s 2-mile-long linear accelerator. As head of...

Sidney D. Drell

Sidney Drell was a senior fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institution and a professor of theoretical physics emeritus at SLAC, where he served as deputy director from 1969 until retiring in 1998. Drell initiated a program at the Hoover Institution to...

After joining the Stanford chemistry faculty in 1973, Keith Hodgson started a fundamental research program using X-rays from SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Light Source (SSRL) to study chemical and biological structure; later he served as SSRL director. As deputy lab...

Persis S. Drell (Past deputy director)

Physicist Persis Drell joined the Stanford faculty in 2002 as a professor and director of research at SLAC. She worked on the construction of the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope before being appointed deputy lab director in 2005, working with fellow...

Norbert Holtkamp was SLAC's deputy director and project director for the construction of LCLS-II. He is a SLAC professor of photon science and of particle physics and astrophysics. He works on strategic initiatives, including approximately $2 billion in construction now...

As SLAC’s chief operating officer from 2017 to 2022, Brian Sherin oversaw the lab’s Business & Technology Services, Facilities & Operations, Human Resources, Communications, and Environment, Safety & Health divisions.