In brief: Radiation damage lowers melting point of potential fusion reactor material

SLAC’s ‘electron camera’ films rapidly melting tungsten and reveals atomic-level material behavior that could impact the design of future reactors.

By Manuel Gnida

Radiation damage lowers the melting point of the metal tungsten, an effect that could contribute to material failure in nuclear fusion reactors and other applications where materials are exposed to particle radiation from extremely hot fusion plasma. That’s the result of a study, published today in Science Advances, that was led by researchers at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

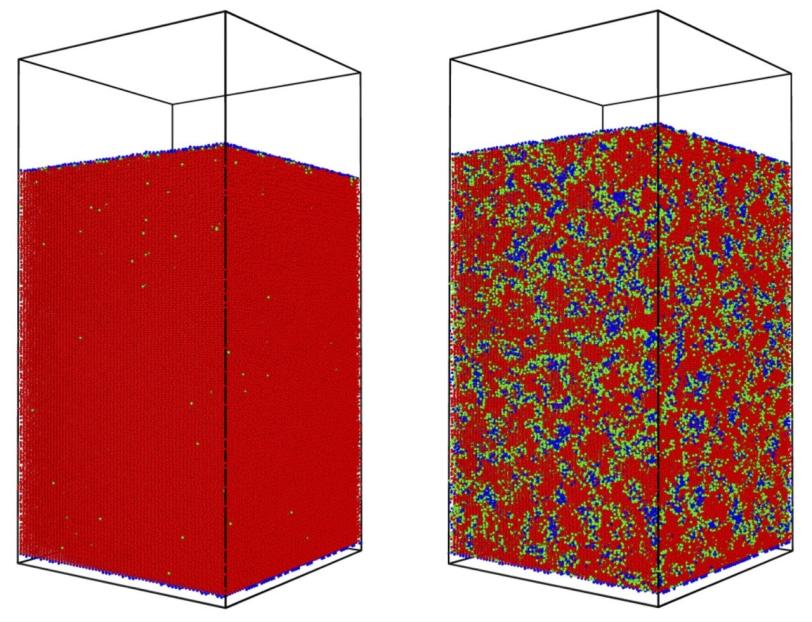

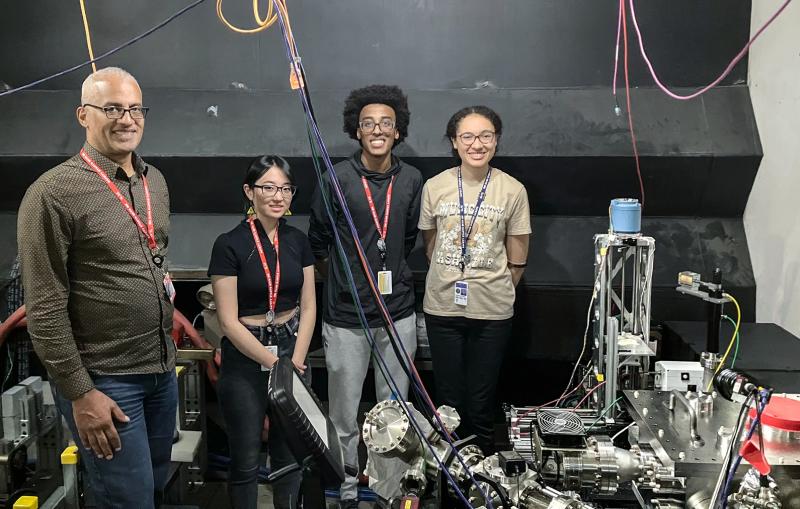

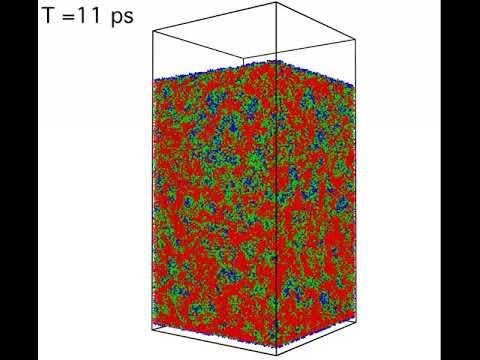

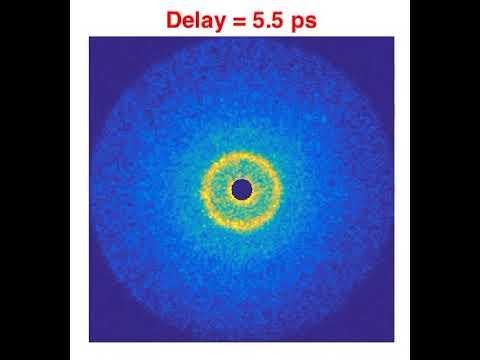

To mimic the damage materials can sustain under the harsh conditions of a fusion experiment, the team bombarded tungsten samples with energetic ions. Then, they heated the samples with a high-power laser and “filmed” how the samples’ atoms responded with SLAC’s ultrafast “electron camera,” an instrument for ultrafast electron diffraction (MeV-UED). They found that damaged tungsten liquefied at a lower temperature than pristine tungsten. Combining their experimental data with advanced simulations allowed the researchers to quantify, for the first time, how the ultrafast melting process is affected by radiation damage.

Computer Simulation: Ultrafast Melting of Tungsten

The results could aid the design of fusion reactor materials, for instance by providing ideas for dealing with damage sites, the scientists said. They also underline the importance of high-energy upgrades to SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray laser and of power enhancements to its laser facility, which would pave the way for even more detailed studies of materials under extreme conditions.

SLAC’s Mianzhen Mo and Samuel Murphy from Lancaster University in the UK were the study’s lead authors. SLAC’s Siegfried Glenzer was the principal investigator. Other contributing institutions were Imperial College London in the UK and DOE’s Los Alamos National Laboratory. SLAC’s MeV-UED instrument is part of LCLS, a DOE Office of Science user facility. This work was largely funded by the Office of Science.

UED Data: Ultrafast Melting of Tungsten

Related content:

Atomic movie of melting gold could help design materials for future fusion reactors

Citation

Mianzhen Mo et al., Science Advances, 24 May 2019 (10.1126/sciadv.aaw0392)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit energy.gov/science.