Yijing Huang wins 2022 LCLS Young Investigator Award for work on controlling unique structures of semiconductors

The award celebrates Huang’s achievements studying atom-scale physics with fast X-ray pulses.

By Isabel Swafford

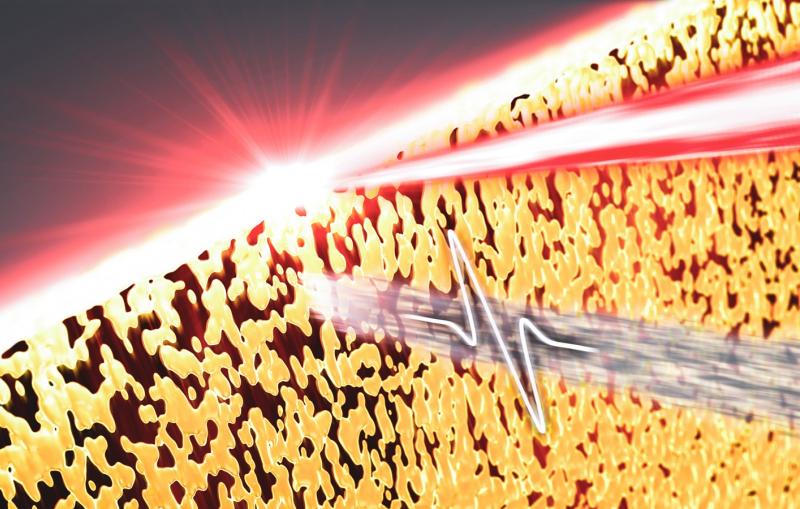

For decades, materials scientists have focused on materials that are relatively balanced and unchanging – but not Yijing Huang, a postdoctoral scholar at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. With the aid of SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), Huang works to understand the atomic-scale structure of systems that are out of balance and changing, such as the unique structures that arise in semiconductors when struck by very brief laser pulses.

In recognition of those efforts, the LCLS User Executive Committee has honored Huang with its 2022 LCLS Young Investigator Award. The award recognizes outstanding contributions by early-career scientists who perform research using SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray free-electron laser. LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

“I am very excited to receive this award,” Huang said. “Actually, I was so excited just to be a finalist. The other two finalists are very experienced researchers.”

Huang was selected as a finalist among two other scientists: Archana Raja and Philipp Simon, both from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

David Reis, Huang's supervisor and the director of SLAC and Stanford University’s PULSE Institute, nominated her for research on newly observed, non-equilibrium structures in the semiconductor tin selenide. Huang presented the work at the 2022 LCLS/SSRL Annual Users’ Meeting in September.

“The results she presented are exemplary of how X-ray free-electron lasers such as LCLS are essential tools to help discover novel states of matter and understand their atomic-scale dynamics,” said Reis.

Only forwards, never backwards

Non-equilibrium states occur all around us all the time. Photosynthesis is one example, as is burning a match. Any process that has a start and a finish – and that cannot be reversed – can be thought of as being in a state of non-equilibrium. But in the field of physics, non-equilibrium states are much hazier and not yet well understood.

“Physicists have been thinking about physics in equilibrium for centuries,” said Huang. “But they only started to think about weird stuff like non-equilibrium states more recently. There are a lot of new things to explore both in terms of the physics and its applications.”

Huang studies how semiconductor materials such as tin selenide can be manipulated and controlled in these special non-equilibrium states. By using the LCLS X-ray free-electron laser, she can create the conditions necessary for non-equilibrium states to occur and study their properties, such as how long they last. By better understanding these properties, researchers hope to discover ways to build faster electronic switches and boost computational power, among many other potential applications.

Merry beam time

As Huang prepares to move to a new position at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, she says she's grateful for her time at LCLS and the training it provided her. Receiving time to use the LCLS X-ray free-electron laser beam, she said, is almost as special as getting a gift during the holidays.

“There's a joke that we have among ourselves, that there's weekdays, there's weekends and holidays, and then there's beam time,” Huang said. “When it's assigned to you, even if it's Thanksgiving or Christmas, it really doesn't matter. You have to be there 24/7.”

Like a present, beam time is also precious, meaning researchers like Huang have to be efficient. Quickly adapting experimental methods and redoing essential calculations as new information comes in are essential for a successful research session.

“It's really good scientific training because it forces you to decide what's important. Beam time really requires you to think hard to understand the results as they come out,” Huang said.

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.