A Goldilocks promoter for a silver catalyst

Nickel dopants could improve sustainable production of ethylene oxide, a chemical widely used in industrial manufacturing.

By Chris Patrick

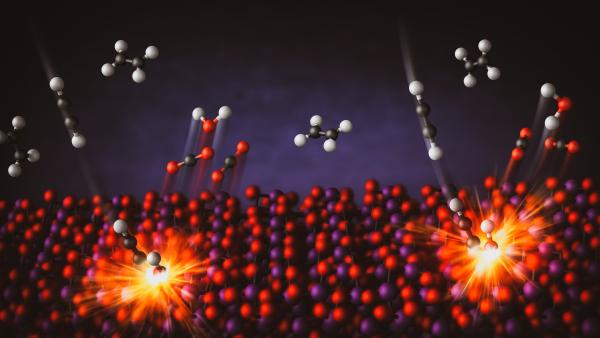

Plastics, textiles, detergents, adhesives and antifreeze all have something in common: They were made using ethylene oxide. This colorless gas, a chemical building block in the industrial production of many materials, is itself produced by reacting oxygen with ethylene. However, maximizing the amount of ethylene oxide produced poses unique challenges.

Adding chlorine increases the efficiency of ethylene oxide production by 25 percent. But chlorine, which is corrosive to metal equipment, has its own drawbacks. Writing in Science, researchers at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), Tufts University, Brookhaven National Laboratory and Tulane University identified nickel as a promoter that can enhance the selectivity of the silver catalyst by about 25 percent, roughly the same amount as chlorine, but with fewer downsides. The team studied the interaction of nickel with the silver catalyst using X-rays from the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

“From an environmental standpoint, if you remove chlorine, that’s one less toxic and corrosive material out of the process stream,” said Adam Hoffman, a staff scientist at SLAC who contributed to this work. “And if you can improve a catalyst’s activity to a target chemical, it improves the sustainability of the process as a whole.”

Charles Sykes, a chemist at Tufts University who led the effort, said it also makes financial sense. “Every one percent increase in the efficiency of the process saves around $200 million annually,” he said.

SLAC Staff ScientistIf you remove chlorine, that’s one less toxic and corrosive material out of the process stream.

Selective combustion streamlines ethylene production

Supported by SLAC’s catalysis group, researchers have discovered a promising method to remove contaminants during the making of polymers.

A more selective catalyst doesn’t only maximize the amount of product, it is also more efficient overall. Post reaction, ethylene oxide must be separated from the side products and residual reactants, a process that requires additional energy inputs. If the reaction is more selective to ethylene oxide to begin with, it is easier to purify.

Other non-chlorine promoters for this reaction exist, including molybdenum, rhenium and cesium. However, these promoters only enhance the selectivity of the silver catalyst when used in tandem with chlorine. In addition to not requiring chlorine, nickel, an abundant earth metal, is cheaper and less toxic than these alternatives.

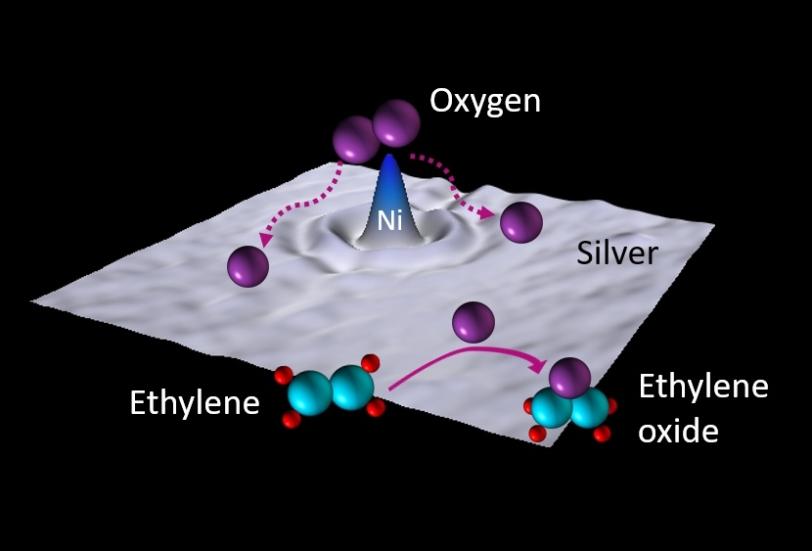

The UCSB team, working with Hoffman, led spectroscopy measurements at the SSRL that used X-rays to probe the nickel-silver interaction. These measurements showed the nickel and silver, two elements that typically don’t mix well, were incorporated together instead of being segregated in the catalyst.

“The SLAC capabilities provided a unique approach for directly measuring nickel interactions with silver, which was a real challenge given the only 200 parts per million of nickel that is in each sample,” said Phil Christopher, a professor who led the team at UCSB.

“Our spectra showed the nickel is interacting with the silver, giving credence to the idea that they’re comingled and supporting the theory calculations,” Hoffman said.

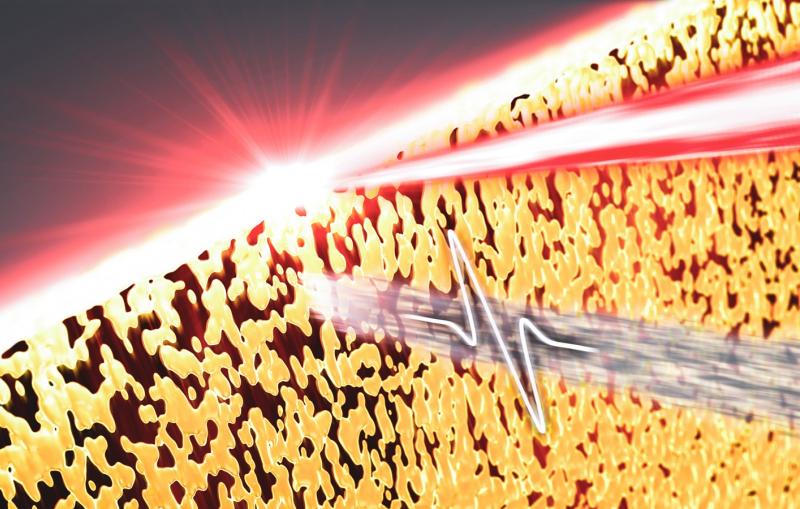

During the production of ethylene oxide, oxygen molecules stick to the silver surface, which breaks them into individual oxygen atoms that can readily react with ethylene. When nickel is added, it decorates the surface of the silver catalyst. There, it stabilizes the oxygen on the silver surface without binding to it too strongly, providing a steady flow of activated oxygen atoms ready to react with ethylene and produce ethylene oxide.

“Nickel’s ability to stabilize the oxygen without holding onto it too strongly and preventing it from reacting makes it a Goldilocks promoter for this reaction,” Hoffman said. This just-right promoter may lead the way toward more environmentally friendly industrial production of ethylene oxide.

Sykes said that it has been his favorite research project to date, “starting six years ago with Matthew Montemore at Tulane who predicted nicked might work, to all the fundamental research that led to the discovery of a new catalyst formulation for this important reaction. It’s been a true team effort.”

Portions of the research were carried out at the National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS-II) at the DOE’s Brookhaven National Laboratory. The research was funded in part by the DOE Office of Science and the National Science Foundation. SSRL and NSLS-II are DOE Office of Science user facilities.

Citation: Anika Jalil et al., Science, 20 February 2025 (10.1126/science.adt1213)

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.