Scientists Watch Quantum Dots 'Breathe' in Response to Stress

Nanocrystal Study at SLAC's X-ray Laser Could Aid in the Design of New Materials

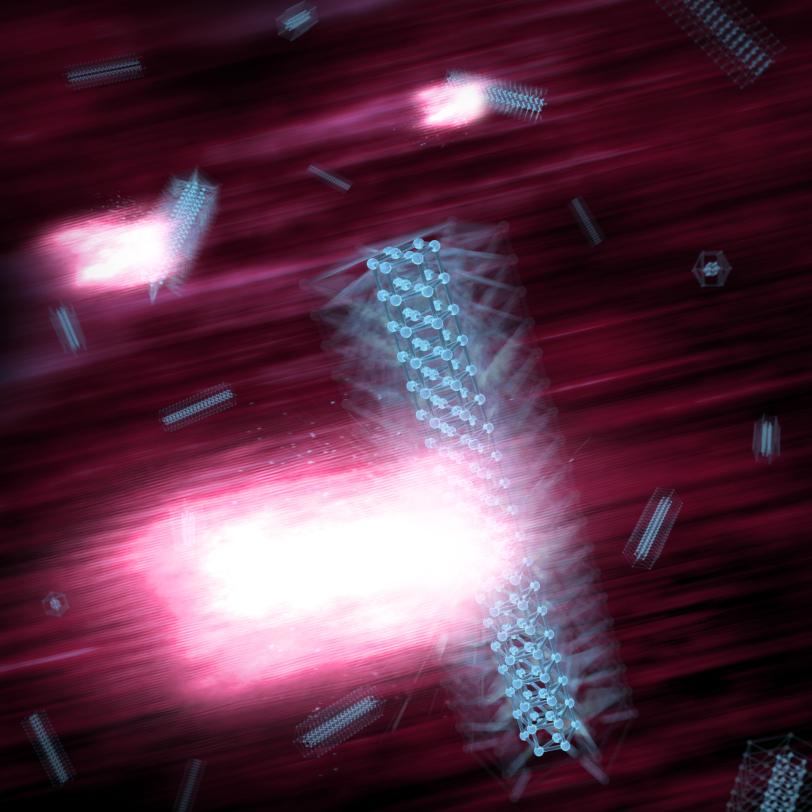

Researchers at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory watched nanoscale semiconductor crystals expand and shrink in response to powerful pulses of laser light. This ultrafast “breathing” provides new insight about how such tiny structures change shape as they start to melt – information that can help guide researchers in tailoring their use for a range of applications.

In the experiment using SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray laser, a DOE Office of Science User Facility, researchers first exposed the nanocrystals to a burst of laser light, followed closely by an ultrabright X-ray pulse that recorded the resulting structural changes in atomic-scale detail at the onset of melting.

“This is the first time we could measure the details of how these ultrasmall materials react when strained to their limits,” said Aaron Lindenberg, an assistant professor at SLAC and Stanford who led the experiment. The results were published March 12 in Nature Communications.

Getting to Know Quantum Dots

The crystals studied at SLAC are known as "quantum dots" because they display unique traits at the nanoscale that defy the classical physics governing their properties at larger scales. The crystals can be tuned by changing their size and shape to emit specific colors of light, for example.

So scientists have worked to incorporate them in solar panels to make them more efficient and in computer displays to improve resolution while consuming less battery power. These materials have also been studied for potential use in batteries and fuel cells and for targeted drug delivery.

Scientists have also discovered that these and other nanomaterials, which may contain just tens or hundreds of atoms, can be far more damage-resistant than larger bits of the same materials because they exhibit a more perfect crystal structure at the tiniest scales. This property could prove useful in battery components, for example, as smaller particles may be able to withstand more charging cycles than larger ones before degrading.

A Surprise in the ‘Breathing’ of Tiny Spheres and Nanowires

In the LCLS experiment, researchers studied spheres and nanowires made of cadmium sulfide and cadmium selenide that were just 3 to 5 nanometers, or billionths of a meter, across. The nanowires were up to 25 nanometers long. By comparison, amino acids – the building blocks of proteins – are about 1 nanometer in length, and individual atoms are measured in tenths of nanometers.

By examining the nanocrystals from many different angles with X-ray pulses, researchers reconstructed how they change shape when hit with an optical laser pulse. They were surprised to see the spheres and nanowires expand in width by about 1 percent and then quickly contract within femtoseconds, or quadrillionths of a second. They also found that the nanowires don’t expand in length, and showed that the way the crystals respond to strain was coupled to how their structure melts.

In an earlier, separate study, another team of researchers had used LCLS to explore the response of larger gold particles on longer timescales.

“In the future, we want to extend these experiments to more complex and technologically relevant nanostructures, and also to enable X-ray exploration of nanoscale devices while they are operating,” Lindenberg said. “Knowing how materials change under strain can be used together with simulations to design new materials with novel properties.”

Participating researchers were from SLAC, Stanford and two of their joint institutes, the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES) and Stanford PULSE Institute; University of California, Berkeley; University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany; and Argonne National Laboratory. The work was supported by the DOE Office of Science and the German Research Council.

Citation: E. Szilagyi et al., Nature Communications, 12 March 2015 (10.1038/ncomms7577)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.