Snapping pictures of tiny, flash-frozen things with cryogenic electron microscopy is revolutionizing biology and technology.

By Glennda Chui

What is cryo-EM?

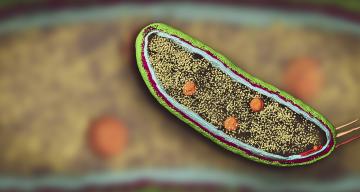

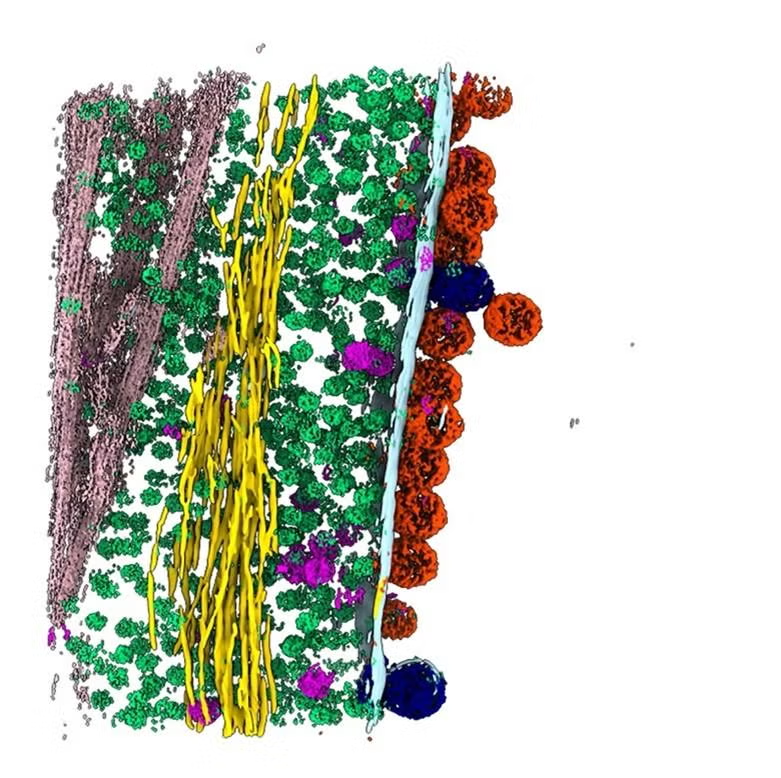

Imagine yourself shrunk to a tiny size and plopped inside a human cell. You’re stunned to discover it’s nothing like what you imagined from the neatly labeled drawings and microscopic images you’ve seen in the past. As you look around in astonishment, the interior seems vast but incredibly crowded, and everything’s in motion all the time. Proteins and other biomolecules jostle and bump into each other in the gel-like cytoplasm that fills the interior, while molecular machines hustle to perform all the tasks the cell needs. Specialized structures generate energy, carry out everything from chemical reactions to cell division, stand sentry at the cell’s gates, assemble new molecules and recycle old ones, and lug cargo down microscopic highways.

A “spike” from a coronavirus

A rotating 3D image shows the detailed cryo-EM structure of a “spike” from a coronavirus that causes cold symptoms – a milder relative of the virus that causes COVID-19. Just like in covid, these spikes start infections by binding to cells. (K. Zhang et al., Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics Discovery, 2020)

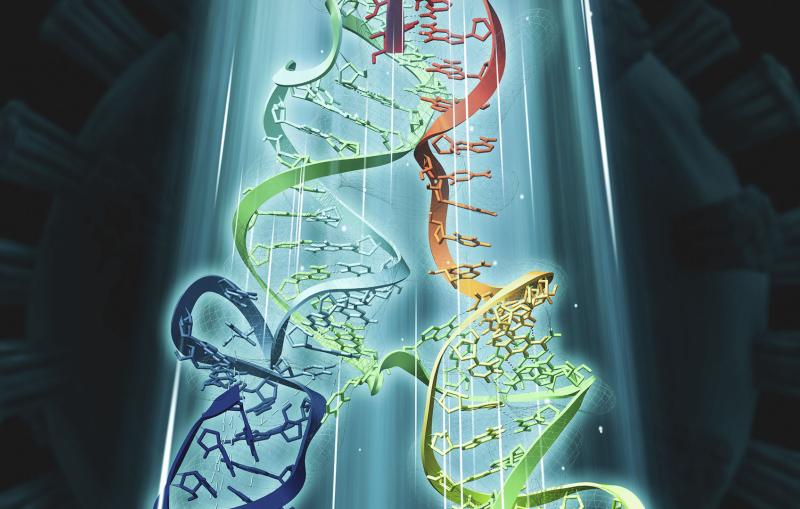

Since shrinking yourself isn’t possible, you need a tool to view this amazing landscape, and that’s where cryo-EM, or cryogenic electron microscopy, comes in. It allows scientists to make detailed 3D images of DNA, RNA, proteins, viruses, cells and the tiny molecular machines within the cell, revealing how they change shape and interact in complex ways while carrying out life’s functions. By stringing thousands of these snapshots together into stop-action movies and virtual reality flythroughs, we can watch biology in action.

Understanding the cell and its bustling inhabitants has been a major scientific quest for hundreds of years. Today, thanks to this revolutionary technology, we can get a much closer and more realistic view, in 3D and in atomic detail.

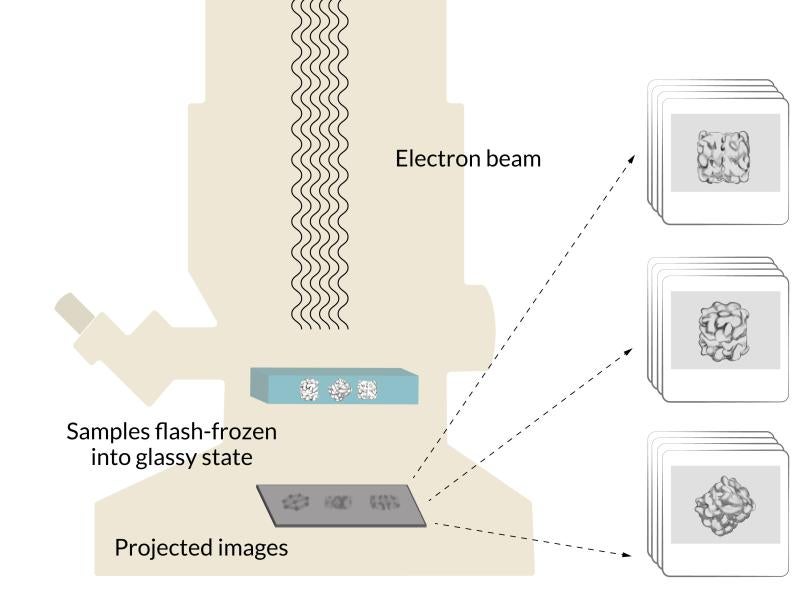

Invented 40 years ago as an offshoot of electron microscopy, cryo-EM flash-freezes samples into a glassy state and probes them with beams of electrons. It’s improved so much and so fast in the past 10 years that it can now make clear images of individual atoms. Those rapid advances earned three of its key developers a 2017 Nobel Prize.

What is Cryogenic Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM)

How does it work?

Quantum mechanics tells us that fundamental bits of matter like the electron are both particles and waves. Cryo-EM takes advantage of the fact that the electron has a very tiny wavelength – much shorter than wavelengths of light – so it can make clear images of equally tiny things.

Cooling a sample

A researcher prepares a plunge freezer for a cryo-EM experiment. Plunging samples into liquid ethane instantly stops the movements of cellular components so the electron beam can get clear images. Plunge freezing also keeps samples hydrated and minimizes damage from the electron beam.

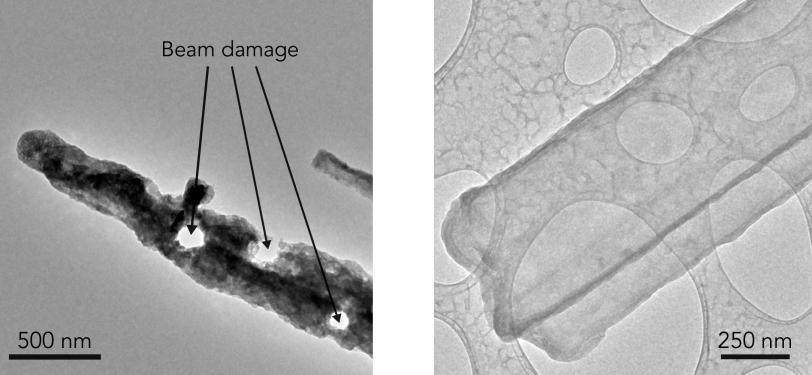

But a tiny wavelength is not enough. An intense electron beam can damage or destroy a delicate sample. Freezing samples helps protect them, but it has to be a particular type of freezing that doesn’t form ice crystals, which would disrupt the natural state of the sample, and that’s fast enough to capture that natural state, like a camera with a very fast shutter speed.

Cryo-EM gets around both of those problems by freezing samples into a glass-like state.

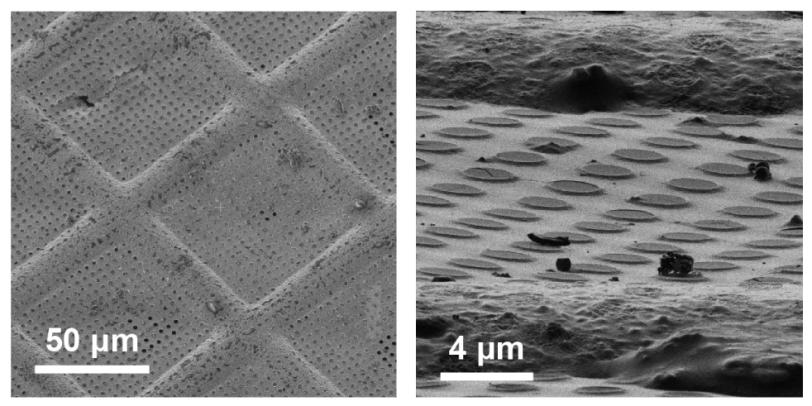

Researchers extract the specimens they want to study – in this case, let’s say they’re looking at a particular type of protein molecule – and suspend them in water, where they float freely. Next, they deposit a drop of water containing thousands of copies of the protein across a grid of tiny holes in a carbon net.

A robotic arm plunges the grid into liquid ethane that’s been cooled in a bath of liquid nitrogen, and the water and its cargo of proteins instantly freeze into a glassy state.

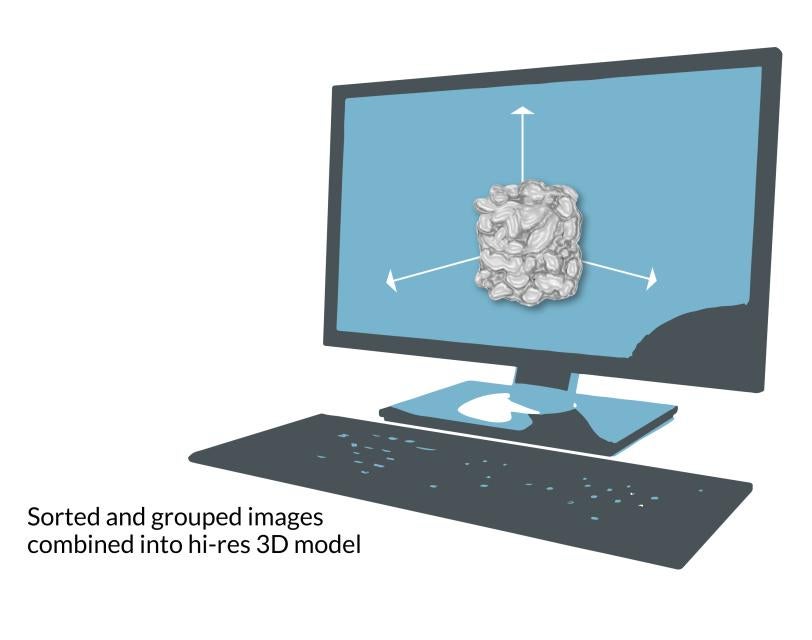

The grid is put into a transmission electron microscope, where an electron beam travels through the sample and casts the 2D shadows of the protein molecules onto a detector. Since the proteins were floating in random orientations at the instant they were vitrified, each shadow is unique. Computer software groups similar 2D shadows together and combines them to produce a more detailed array of 2D images, which are combined again into a 3D reconstruction of the molecule. Researchers can move and rotate this reconstruction in a computer to look at it from all sides.

Making 3D models

Cryo-EM is a version of electron microscopy that freezes many copies of a delicate sample into a glassy state and hits them with an electron beam. Electrons pass through the copies to create images into a high-res 3D model of the sample.

What’s special about our cryo-EM facilities?

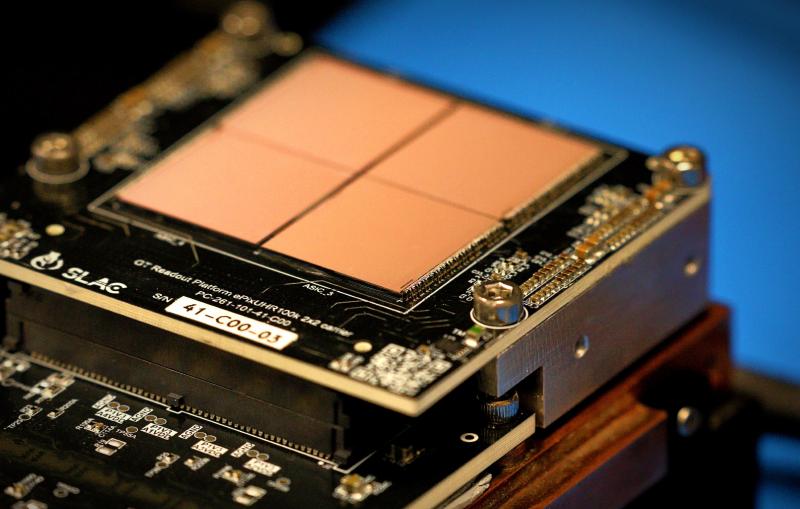

SLAC and Stanford host one of the world’s leading facilities for doing cryo-EM research, developing ways to make it cheaper, more powerful and easier to use, and making it available to researchers across the country. Our partnership with the university and the array of cryo-EM instruments on both campuses create opportunities for us to collaborate in new and creative ways.

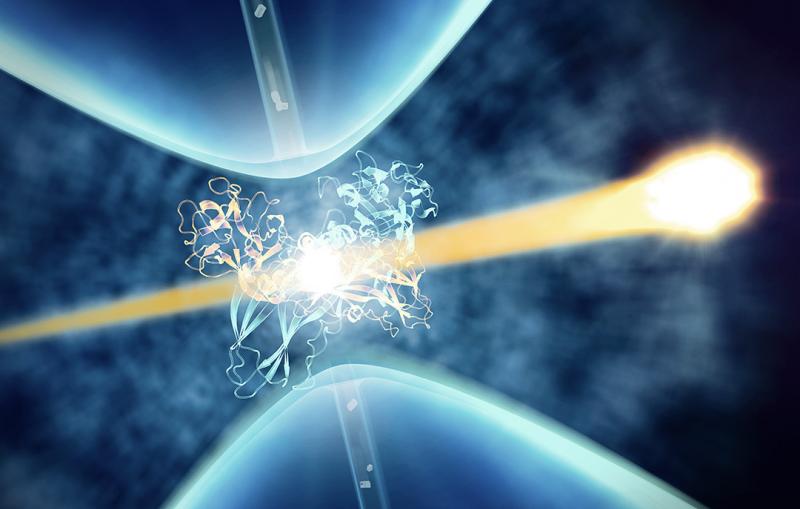

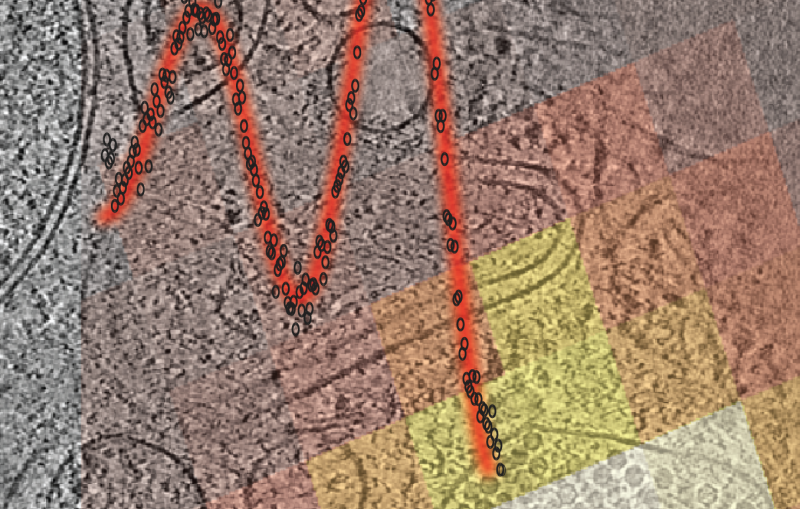

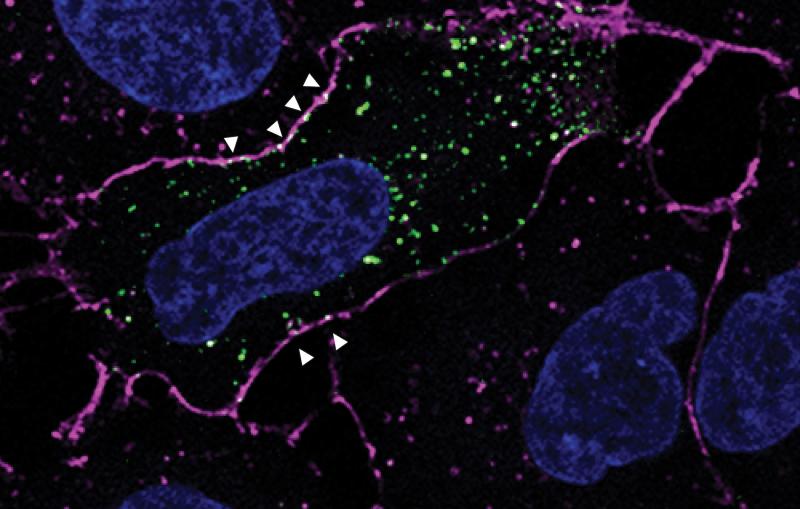

In one exciting new development, researchers at SLAC and Stanford are coordinating cryo-EM with other cutting-edge imaging techniques to pinpoint the locations of individual molecules within a bacterial cell for the first time.

This new approach has potential to answer fundamental questions about the molecular machinery of bacteria, viruses, parasites and processes like photosynthesis.

Cryo-EM science at SLAC and Stanford

Super-detailed images and movies made with cryo-EM have given SLAC and Stanford researchers important new information about chicken pox, coronavirus infections, mosquito-transmitted diseases like chikungunya, and how organisms out in nature assemble antibiotics, among many other things.

We’re exploring other ways to use cryo-EM to investigate things like solar panel materials, semiconductor films and catalysts used in electrochemistry.

(Y. Li et al., Science)

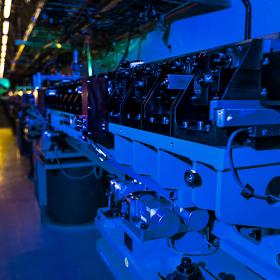

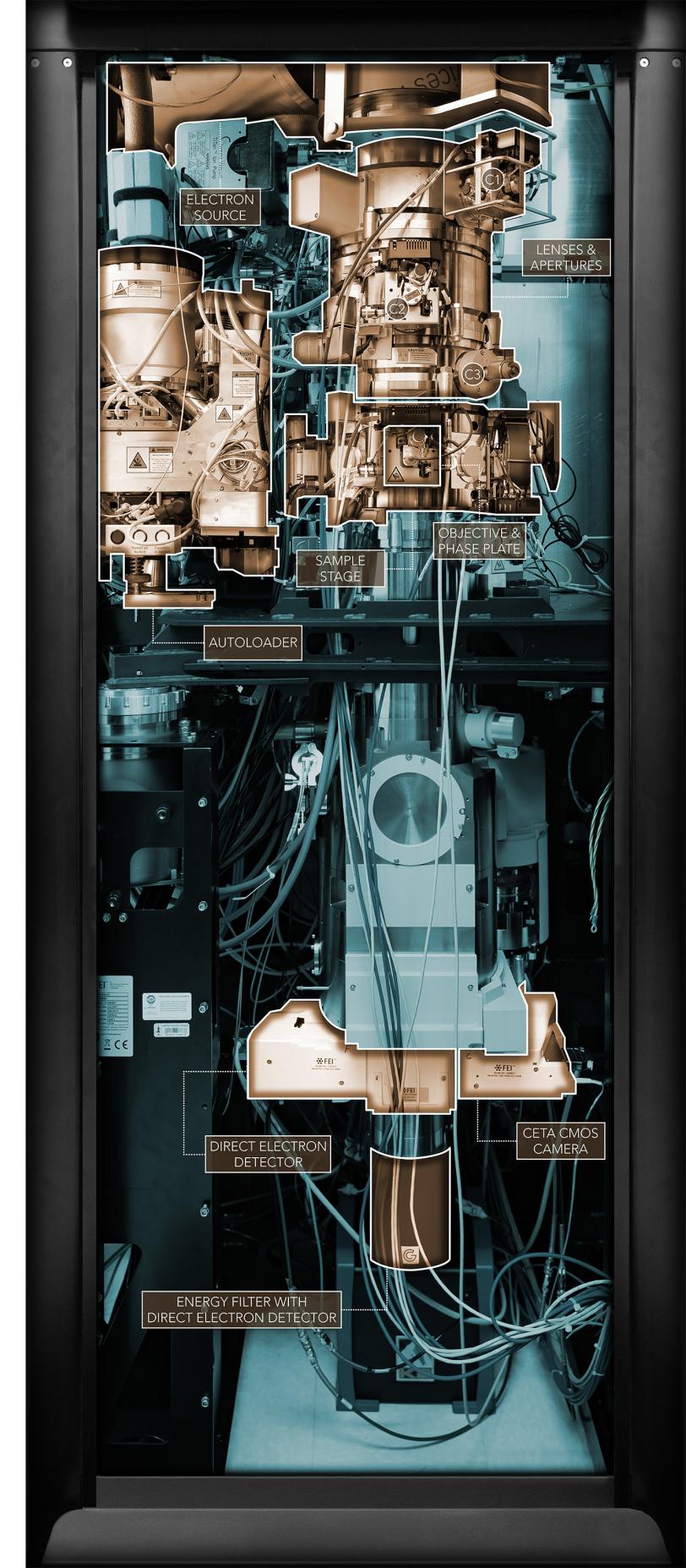

See inside

A photo of one of SLAC’s cryo-EM microscopes is highlighted to identify its major working parts.

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.