How tiny hinges bend the infection-spreading spikes of a coronavirus

Disabling those hinges could be a good strategy for designing vaccines and treatments against a broad range of coronavirus infections, including COVID-19.

By Glennda Chui

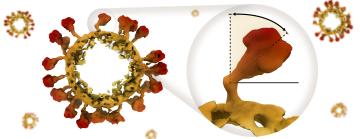

A coronavirus uses protein “spikes” to grab and infect cells. Despite their name, those spikes aren’t stiff and pointy. They’re shaped like chicken drumsticks with the meaty part facing out, and the meaty part can tilt every which way on its slender stalk. That ability to tilt, it turns out, affects how successfully the spike can infect a cell.

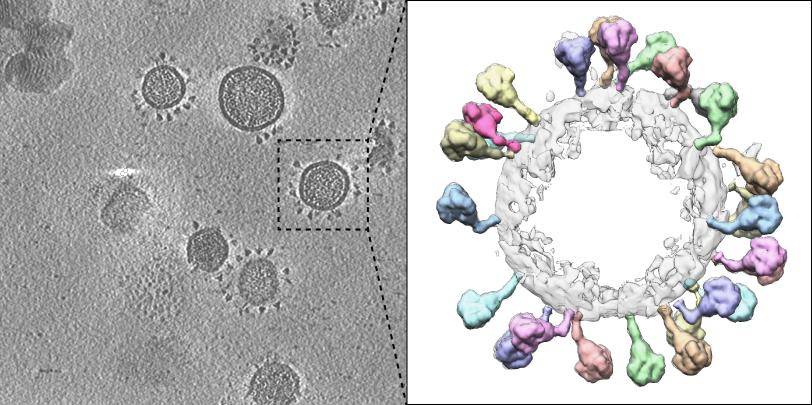

Now researchers from the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University, along with collaborators at three more universities, have obtained high-resolution images of intact coronavirus spikes on the surfaces of virus particles; identified a tiny hinge surrounded by sugar molecules that allows the spike’s glob-like “crown” to bend on its stalk; and measured how far it can tilt in any direction.

While the study was carried out on a much less dangerous cousin of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, it has implications for COVID-19, too, since both viruses bind to the same receptor on a cell’s surface to initiate infection, said Jing Jin, a biologist at Vitalant Research Institute and adjunct assistant professor at the University of California, San Francisco who performed virology experiments for the study.

The results, she said, suggest that disabling the spike’s hinges could be a good way to prevent or treat a wide range of coronavirus infections.

The team also discovered that each coronavirus particle is unique, both in its underlying shape and its display of spikes. Some are spherical, some are not; some bristle with spikes while others are nearly bald.

“The spikes are floppy and move around, and we used a combination of tools to explore all their possible angles and orientations,” said Greg Pintilie, a Stanford scientist who developed detailed 3D models of the virus and its spikes. Seen up close, he said, each spike is different from all the rest, mainly in its direction and degree of tilting.

The research team reported its findings in Nature Communications.

(Greg Pintilie / Stanford University)

“Since the pandemic started, most studies have looked at the structures of coronavirus spike proteins that were not attached to the virus itself,” said Wah Chiu, a professor at SLAC and Stanford and co-director of the Stanford-SLAC Cryo-EM facilities where the imaging was done. “These are the first images made of the spikes of this strain of coronavirus while they’re still attached to the virus particles.”

SARS-CoV-2’s more benign cousin

The study has roots in the early days of the pandemic, when research at SLAC shut down except for work aimed at understanding, preventing and treating COVID-19 infections.

Because experiments with the actual SARS-CoV-2 virus can only take place in high-level (BSL3) biosafety labs, many scientists chose to work with more benign members of the coronavirus family. Chiu and his colleagues selected human coronavirus NL63 as their subject. It causes up to 10% of human respiratory infections, mainly in children and immunocompromised people, with symptoms ranging from mild coughs and sniffles to bronchitis and croup.

In 2020, Chiu said, the team used cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and computational analysis to image the crowns of NL63 spikes with near-atomic resolution.

But because a spike’s stalk is much thinner than its crown, they were not able to get clear, high-resolution images of both at once.

Zooming in on spikes

This study combined information gleaned from a series of experiments to get a much more complete picture.

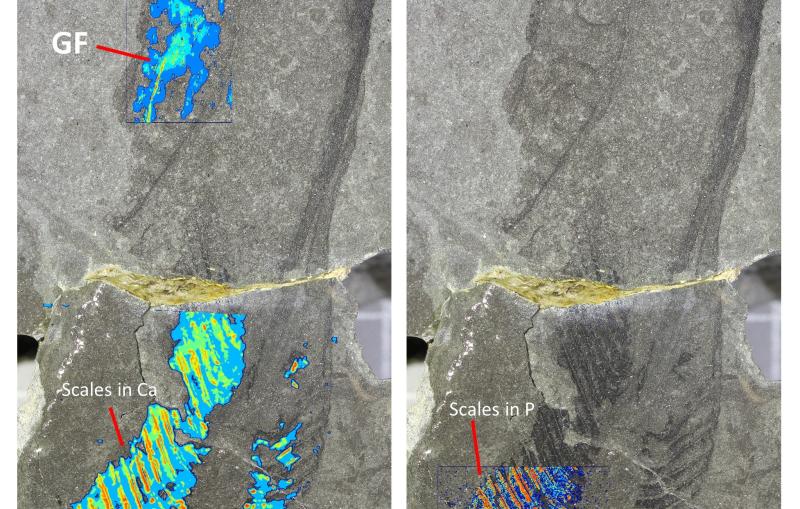

First, Stanford graduate student David Chmielewski used cryogenic electron tomography (cryo-ET) to combine cryo-EM images of viruses that were taken from different angles into high-resolution 3-D images of more than a hundred NL63 particles.

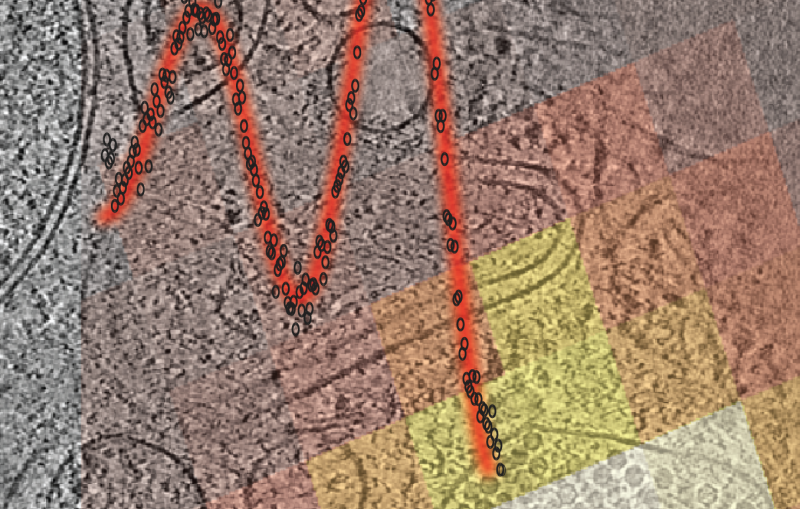

SLAC senior scientist Michael Schmid plugged those images into a 3D visualization tool and discovered that each of a particle’s spikes was bent in a unique way. Another SLAC scientist, Muyuan Chen, used advanced image reconstruction to create maps showing the average density of the spikes’ crowns and stalks.

Zooming in on one of those spikes, biological chemist Lance Wells at the University of Georgia used a technique called mass spectrometry to pinpoint the site-specific chemical compositions of the 39 sugar chains attached to each of the spike’s three identical proteins.

Finally, Abhishek Singharoy, a computational biophysicist at Arizona State University, and his student, Eric Wilson, integrated all those measurements into atomic models of the spikes’ crowns and stalks at different bending angles, and carried out further simulations to see how far and how freely a spike can bend.

(Greg Pintilie / Stanford University)

“It turns out that no matter what, the spikes have a preferred bending angle of about 50 degrees,” Chiu said, “and they can tilt up to 80 degrees in any direction in the simulation, which matches well with our cryo-ET experimental observations.”

The bending occurred at a place on the stalk, just below the crown, where a particular cluster of sugar molecules clung to the protein, forming a hinge. Computer simulations suggested that changes in the structure of this hinge would affect its ability to bend, and lab experiments went one step further: They showed that mutations in the protein part of the hinge made the spike much less infectious. This suggests that targeting the hinge could provide an avenue to fight the virus.

“People working on the more dangerous coronaviruses, including MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, have identified a region equivalent to this one and discovered antibodies targeting this region,” Jin said. “That tells us it’s a critical region that is highly conserved, meaning that it has stayed much the same over the course of evolution. So maybe by targeting this region in all coronaviruses, we can come up with a universal therapy or vaccine.”

This work was supported by the National Virtual Biotechnology Laboratory, a group of Department of Energy national laboratories that was focused on responding to the COVID-19 pandemic with funding provided by the Coronavirus CARES Act; the National Science Foundation; and the National Institutes of Health.

Citation: David Chmielewski et al., Nature Communications, 7 November 2023 (10.1038/s41467-023-42836-9)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.