X-ray free-electron lasers are like X-ray microscopes, allowing scientists to spot the intricate movements of atoms and molecules and capture their motion in snapshots that can be strung together into “molecular movies.”

What is an X-ray free-electron laser?

XFELs produce powerful X-ray pulses that reveal the intricate movements of atoms and molecules. Scientists capture these motions in snapshots that can be strung together into “molecular movies” of materials, chemistry and biology in action.

These facilities produce pulses as short as millionths of a billionth of a second and about 100 times more intense than all the sunlight hitting the Earth’s surface focused onto a thumbnail. That’s more than enough to destroy most samples. Fortunately, the pulses are also like nimble cat burglars that snatch all the information scientists need from the delicate samples in the instant before they’re blown apart. XFELs also allow scientists to watch atomic and molecular processes play out in conditions very similar to the environments where they naturally take place.

At XFELs, scientists have uncovered the 3D molecular structure of proteins involved in transmitting disease, developed next-generation drug therapies, taken the first live snapshots of fleeting steps in photosynthesis that generate the oxygen we breathe and studied the microscopic components of air pollution. They can measure stress, strain and failure in advanced aerospace materials and study how matter behaves under the extreme pressures that drive the formation of planets.

XFEL explainer

How do they work?

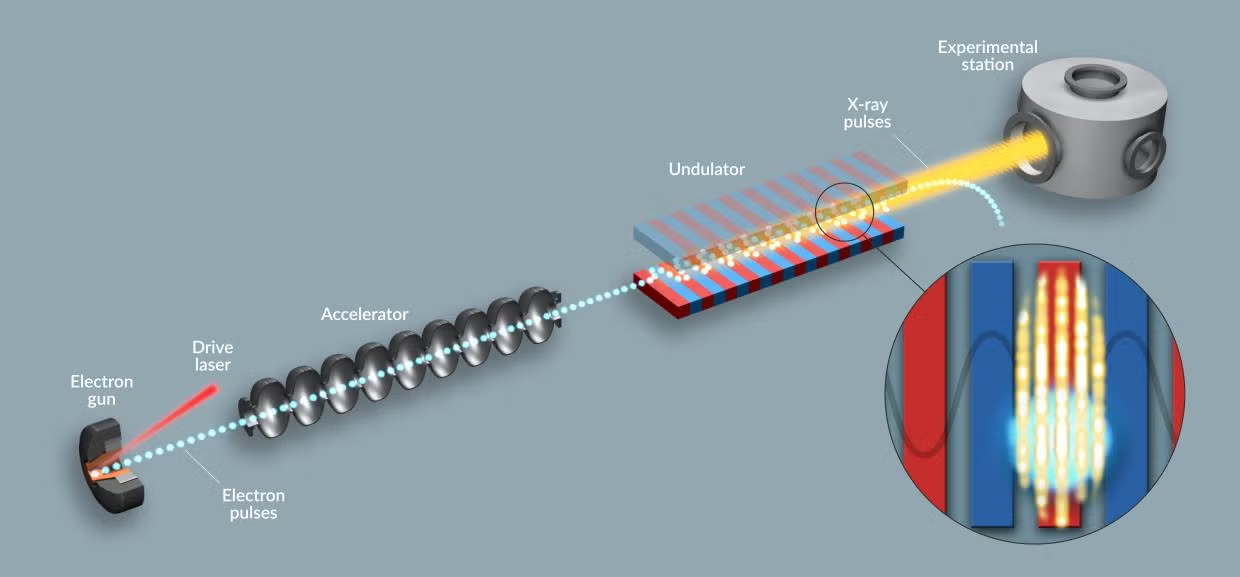

At SLAC’s XFEL the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), a drive laser generates a pulse of ultraviolet light, which travels to an injector "gun" and strikes the surface of a copper plate. The plate releases a burst of electrons, which are accelerated by a series of devices to boost their energy. These pulses then enter the undulator hall, where thousands of intricately arranged magnets wiggle the electron bunches back and forth, forcing them to generate X-rays. As each electron bunch travels with its associated X-rays, they start to interact with each other, causing the waves of X-ray light to synchronize, like a choir singing, and create “coherent” or laser light. The electrons are safely discarded, and the X-ray laser pulses continue in a straight line to LCLS experiments, arriving at a rate of up to 120 pulses per second.

What’s special about LCLS?

LCLS was the world’s first light source of its kind, a free-electron laser producing “hard,” or very high-energy, X-rays. It is a full-service user facility, available free of charge to researchers from around the world. More than 3,000 researchers have conducted experiments at LCLS since it turned on in April 2009. Today, four more hard X-ray FELs are in operation around the world, with more coming online in the next few years.

LCLS has nine experimental instruments and approximately 100 full-time scientists who specialize in techniques for imaging samples, determining their atomic structures and analyzing their chemistry. SLAC is also home to other facilities where scientists can run complementary experiments with X-rays or electron beams.

LCLS’s two undulators produce hard and soft X-rays, and it is the only facility where scientists can shine both types of X-rays on a sample at once. Hard X-rays, which are more energetic, are used to image materials and biological systems at the atomic level. Soft X-rays capture how energy flows between atoms and molecules, allowing researchers to track chemistry in action and gain insights into new energy technologies.

An upgrade to LCLS is now underway. When it’s complete, LCLS will have two linear accelerators – the existing copper linac and a new superconducting one – to feed electrons into the undulators and produce X-ray laser pulses. The beam will fire 8,000 times faster than the original, producing up to a million pulses per second and enabling an entirely new generation of experiments in materials, physical, chemical and biological sciences.

LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

How we use XFELs

Next-generation computers and the power grid

LCLS studies are helping to home in on the most promising materials and methods for transforming the electric power grid and driving next-generation computer components beyond classical limits.

Better, cleaner fuels and chemicals

LCLS X-ray pulses are so fast that they allow us to observe and analyze previously unseen steps in chemical reactions, helping scientists design more efficient reactions to produce fuels, fertilizers and industrial chemicals.

More effective medication with fewer side effects

With its ability to study very tiny crystals under natural conditions, LCLS makes it possible to determine the 3D atomic structure of important receptor proteins that had been out of reach. A better understanding of how certain drugs dock to these proteins could lead to more effective drugs with fewer side effects.

Renewable energy that mimics nature

LCLS allows us to study how plants use energy from sunlight to release oxygen into the air we breathe during a process called photosynthesis. Scientists are also using the tool to study how light affects other living things.

Fusion reactions and seeing inside planets

High-power laser systems at SLAC heat matter to millions of degrees and crush it with billions of tons of pressure per square inch. Scientists use LCLS to measure what happens to matter under these extreme conditions with high precision at very small scales and over very short periods of time.

XFEL science at LCLS

RIXS Experimental Hutch

FACET-II test facility

Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) Undulator Hall

The Time-Resolved Atomic, Molecular and Optical Science (TMO) Hutch

MFX hutch

Cryoplant building

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.