SLAC researchers wield new tools to study water’s enigmatic surface

Water is all around us, yet its surface layer – home to chemical reactions that shape life on Earth – is surprisingly hard to study. Experiments at SLAC’s X-ray laser are bringing it into focus.

By Glennda Chui

Two-thirds of Earth’s surface is covered in water, most of it in oceans so deep and vast that only one-fifth of their total volume has been explored. Surprisingly, though, the most accessible part of this watery realm – the water’s surface, exposed on wave tops, raindrops and ponds full of skittering water striders – is one of the hardest to get to know.

Just a few layers of atoms thick, the surface plays an outsized role in the chemistry that makes our world what it is – from the formation of clouds and the recycling of water through rainfall to the ocean’s absorption of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

“The interface between air and water is where all the action is, but it’s notoriously hard to study,” said Jake Koralek, staff scientist at the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. “When we try to measure its properties, our measurements are dominated by the billions of atoms that make up the bulk of the water. This is true for even the smallest water droplets.”

Linac Coherent Light Source

LCLS takes X-ray snapshots of atoms and molecules at work, revealing fundamental processes in materials, technology and living things.

Now, a research team led by scientists from SLAC has developed a way to overcome that obstacle and collect strong, clear X-ray data from just the surface, using advanced techniques available at SLAC’s X-ray laser, the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS).

“We were able to directly observe key details of how water molecules at the surface interact differently than those in the rest of the water, confirming longstanding speculation,” said Koralek, who led the research with LCLS instrument scientist David J. Hoffman. “This is crucial for understanding chemistry in water-based systems, including life on Earth.”

The research team, which included scientists at DOE’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, the University of California, Berkeley (Berkeley Lab), University of California, San Diego, and the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, published the latest in a series of papers describing this work in Nature Communications.

SLAC Staff ScientistThis first-of-its-kind experimental result, along with cutting-edge theoretical calculations, will have an immediate influence on our understanding of water and of liquids in general.

Water’s special surface

Water is unique among liquids in many ways. Its surface tension is one of the strongest of any liquid we know – so strong that some insects can literally walk on water, and a razor blade carefully placed on the surface can rest there without sinking.

In general, surface tension develops at the boundary where liquid meets air. The molecules of liquid are attracted to each other more than they are attracted to molecules in the air. They gravitate toward each other, forming a thin layer that acts like an elastic skin and resists breaking.

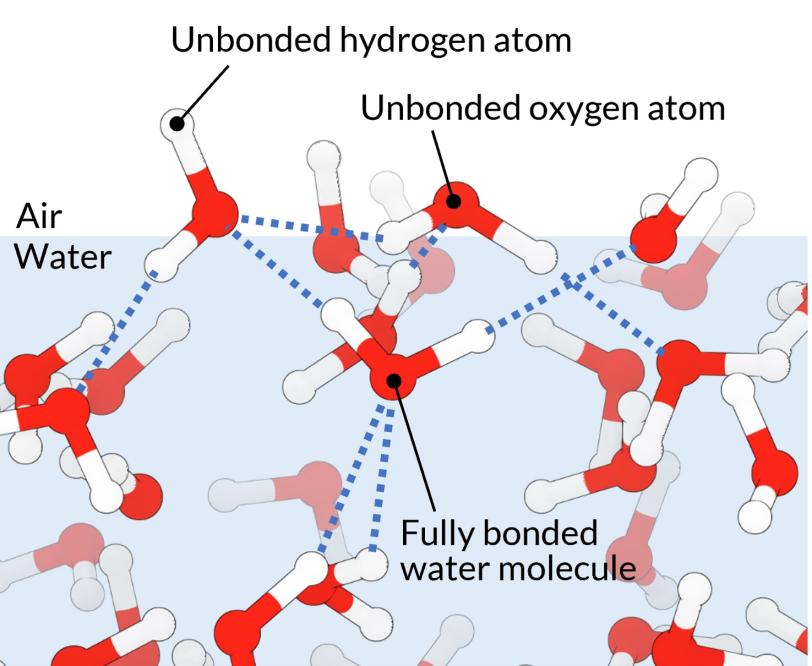

Water molecules, though, don’t just find each other attractive. Each molecule forms four weak, ephemeral bonds with its neighbors, with the hydrogen atoms of one connecting to oxygen atoms of others. In the bulk of the water, these bonds extend in every direction, creating a loose network of molecules that’s constantly breaking and re-forming.

At the very surface, water molecules can only form bonds with the neighbors below them, not with the air above. They are left pointing some of their hydrogen atoms out into the air. This much had been confirmed by earlier measurements.

But, were bond-deprived oxygen atoms at the surface doing the same thing? This seemed to make sense, but until now, no one had directly observed it.

“The surface of water has been studied with a wide range of experimental techniques,” Hoffman said. “But, there are still substantial open questions about the surface’s electronic and molecular structures and how they connect to important macroscopic phenomena, such as how ozone cycles in the atmosphere, how charge is transferred in batteries and the mechanics of how soaps work.”

Shimmering sheets and power boosts

These latest experiments were performed with LCLS’s chemRIXS instrument, which is optimized for cutting-edge experiments in chemistry. Three recent advances were key to making them possible.

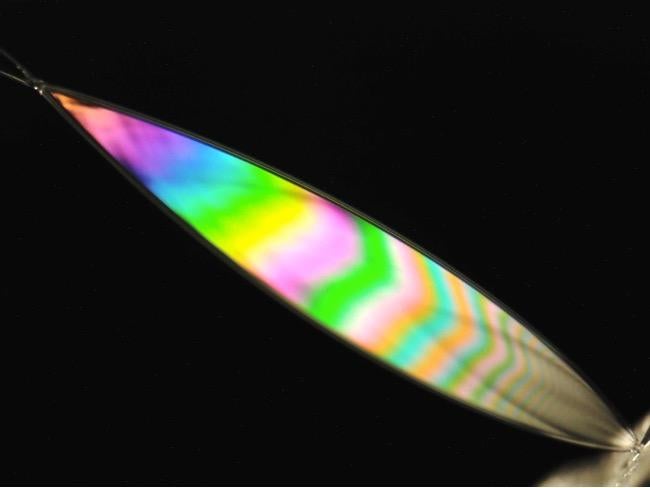

One is a method, developed in 2018 by Koralek and LCLS scientist Daniel DePonte, that carries samples into the path of the LCLS laser in free-flowing sheets of water rather than in cylindrical jets. The sheets are less than 1 micrometer – about 40 millionths of an inch – thick, so thin that they shimmer like soap bubbles. This extreme thinness allows researchers to investigate things they could never see before. The researchers said at the time that they would like to use the thin sheets to look at the nature of water itself, and that’s what they have done here.

Second, recent upgrades to LCLS allowed researchers to hit their water sheets with an X-ray laser beam that delivered ultrashort pulses – less than a millionth of a billionth of a second in duration – each with more than a terawatt (one trillion watts) of power at its peak, arriving at 120 times per second.

Only a beam of the extreme intensity found at an X-ray laser like LCLS could trigger the third crucial component of the experiment: a nonlinear process called second harmonic generation, where two photons of incoming light combine to create one photon of outgoing light with twice the energy. This happens only in the surface layer of water, so it can be used to clearly distinguish what’s happening in the surface layer from what’s happening in the bulk.

In addition, the laser beam was tuned to a wavelength of light in the soft, or lower energy, part of the X-ray spectrum, which is sensitive to the oxygen in water. Then the beam can be used to trace oxygen’s involvement in the hydrogen bonding network that makes water such a unique substance. In this case, it confirmed that oxygen atoms at the surface were also sticking out into the air, unable to accept their desired quota of hydrogen bonds.

“This first-of-its-kind experimental result, along with cutting-edge theoretical calculations, will have an immediate influence on our understanding of water and of liquids in general,” Koralek said. “It paves the way for a broad range of studies on critical aqueous systems that will be of broad interest to the scientific community.”

The team has also been exploring the interface of water with other liquids, adapting their original setup to create incredibly thin, stacked layers of liquid sheets that continually flow into the path of a tabletop laser beam. In 2022, they described experiments where tiny jets of oil and water splashed into each other, forming a thin sheet that allowed the team to study the interface between the two liquids.

And last August, they published a paper comparing the behavior of salts at the water/air and water/oil boundaries, based on experiments led by Shane W. Devlin, a postdoctoral researcher at Berkeley Lab.

Major funding for this research came from SLAC’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development Program (LDRD). It included work at two DOE Office of Science user facilities – SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) and the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC) in Berkeley. The research also made use of the Expanse supercomputer at the San Diego Supercomputing Center, which is supported by the National Science Foundation.

Citation: D. J. Hoffman et al., Nature Communications, 26 Nov. 2025 (10.1038/s41467-025-65514-4)

For questions or comments, contact SLAC Strategic Communications & External Affairs at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.