Why skyrmions could have a lot in common with glass and high-temperature superconductors

Spawned by the spins of electrons in magnetic materials, these tiny whirlpools behave like independent particles and could be the future of computing. Experiments with SLAC’s X-ray laser are revealing their secrets.

By Glennda Chui

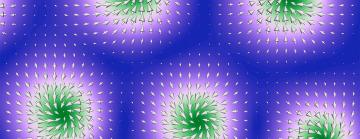

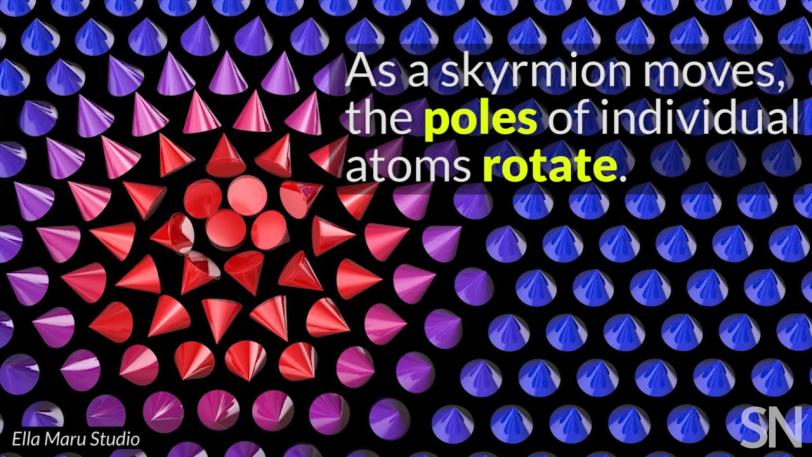

Scientists have known for a long time that magnetism is created by the spins of electrons lining up in certain ways. But about a decade ago, they discovered another astonishing layer of complexity in magnetic materials: Under the right conditions, these spins can form little vortexes or whirlpools that act like particles and move around independently of the atoms that spawned them.

The tiny whirlpools are called skyrmions, named after Tony Skyrme, the British physicist who predicted their existence in 1962. Their small size and sturdy nature – like knots that are hard to undo – have given rise to a rapidly expanding field devoted to understanding them better and exploiting their strange qualities.

“These objects represent some of the most sophisticated forms of magnetic order that we know about,” said Josh Turner, a staff scientist at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and principal investigator with the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES) at SLAC.

“When skyrmions form,” he said, “it happens all at once, throughout the material. What’s even more interesting is that the skyrmions move around as if they are individual, independent particles. It’s like a dance where all the spins are communicating with each other and moving in unison to control the motion of the skyrmions, and meanwhile the atoms in the lattice below them just sit there.”

What's a skyrmion?

Because they are so stable and so tiny – about 1,000 times the size of an atom – and are easily moved by applying small electric currents, he said, “there are lots of ideas about how to harness them for new types of computing and memory storage technologies that are smaller and use less energy.”

Most interesting to Turner, though, is the fundamental physics behind how skyrmions form and behave. He and colleagues from DOE’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the University of California, San Diego have been developing methods for capturing the activities of skyrmions in their natural, undisturbed state with unprecedented detail using SLAC’s X-ray free-electron laser, the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS). It allows them to measure details at the nanoscale – as small as millionths of an inch – and observe changes taking place in billionths of a second.

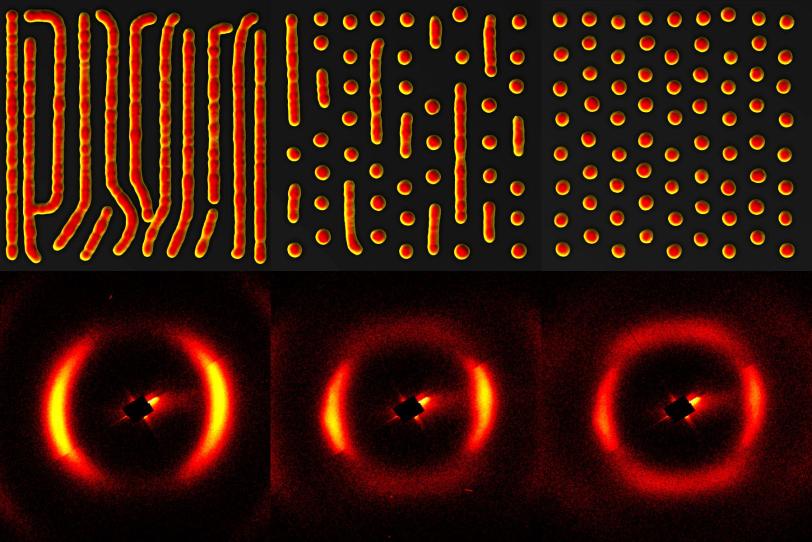

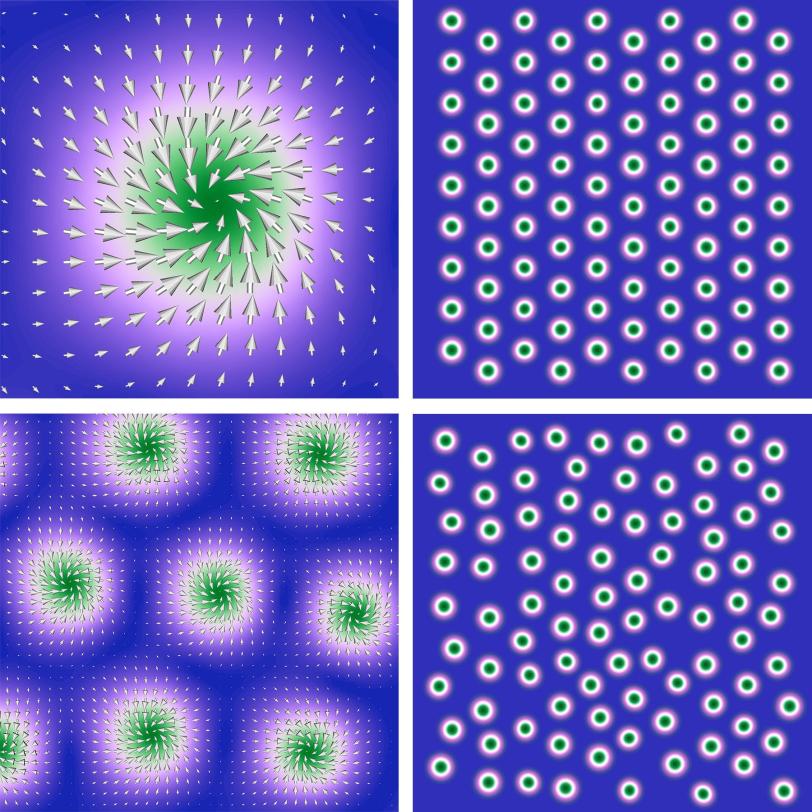

In a series of recent papers, they describe experiments that suggest skyrmions can form a glass-like phase where their movements are so slow that they look like they're stuck, like cars in a traffic jam. Further, they measured how skyrmions’ natural motion with respect to each other can oscillate and change in response to an applied magnetic field, and discovered that this inherent motion never seems to entirely stop. This ever-present fluctuation, Turner said, indicates that skyrmions may have a lot in common with high-temperature superconductors – quantum materials whose ability to conduct electricity with no loss at relatively high temperatures may be related to fluctuating stripes of electron spin and charge.

The research team was able to observe skyrmion fluctuations in a thin magnetic film made of many alternating layers of iron and gadolinium by taking snapshots with the LCLS X-ray laser beam just 350 trillionths of a second apart. They say their method can be used to study the physics of a wide range of materials, as well as their topology – a mathematical concept that describes how an object’s shape can deform without fundamentally changing its properties. In the case of skyrmions, topology is what gives them their robust nature, making them hard to annihilate.

“I think this technique will grow and become very powerful in condensed matter physics, because there aren’t that many direct ways of measuring these fluctuations over time,” said Sujoy Roy, a staff scientist at Berkeley Lab’s Advanced Light Source. “There are a huge number of studies that can be done on things like superconductors, complex oxides and magnetic interfaces.”

Sergio Montoya, a scientist at the Center for Memory and Recording Research at UC San Diego who designed and crafted the material used in this study, added, “This kind of information is important when you develop large-scale electronics and need to see how they behave throughout the material, not just in one little spot.”

Quick snapshots of atomic-scale changes

Montoya started studying the iron-gadolinium film around 2013. At the time, it was already known that skyrmion lattices could form when magnetic fields were applied to certain magnets, and there were strong research efforts to discover new materials capable of hosting skyrmions at room temperature. Montoya carefully crafted the layered materials, adjusting the growth conditions to tune the properties of the skyrmion lattice – “the design and tailoring of the material play a huge role in studies like these,” he said – and teamed up with Roy to examine them with X-rays from the Advanced Light Source.

Meanwhile, Turner and his team at LCLS were developing a new tool that’s like a camera for taking snapshots of atomic-scale fluctuations at extremely fast shutter speeds. Two X-ray laser pulses, each just millionths of a billionth of a second long, hit a sample millionths to billionths of a second apart. The X-rays fly into a detector and form “speckle patterns,” each as unique as a fingerprint, that reveal subtle changes in the material’s complex structure.

“We use soft X-ray pulses with very low intensity that don’t disturb the sample,” explained LCLS scientist Matt Seaberg. “This allows us to get two snapshots that reveal the intrinsic fluctuations in the material and how they change in the very short time span between them.”

It wasn’t long before the LCLS, Berkeley Lab and UC San Diego teams joined forces to aim this new tool at skyrmions.

As Turner put it, “Imagine getting a telescope and choosing where to point it first. Skyrmions seemed like a good choice – exotic magnetic structures with many unknowns about their behavior.”

More powerful tools ahead

Based on what they saw in these experiments, “We think that it’s basically the interaction between adjacent skyrmions that might be causing their intrinsic oscillations,” Seaberg said. “We’re still trying to understand that. It’s hard to see exactly what is oscillating from the type of measurements we made. We’ve had a lot of discussions about how we could figure out what’s happening and what the signals we measured actually mean.”

The specialized instrument they built for these experiments has since been taken apart to make way for other things. But it will be reassembled as part of a new experimental station that’s part of a major LCLS upgrade – an ideal place, the team said, for continuing this new class of experiments on fluctuations in materials like superconductors, as well as a fruitful and collaborative scientific journey that Montoya describes as a “joyful ride.”

Turner said, “It’s remarkable how much we are learning about these kinds of magnetic objects with the special capabilities we have at the LCLS. This project has been a lot of fun. Working with such a great team and with so many things to try, there is literally a treasure trove of information waiting to be uncovered.”

LCLS and ALS are DOE Office of Science user facilities, and major funding for this research came from the Office of Science, including an Early Career Research Program award to Josh Turner.

Citations:

Vincent Esposito et al., Applied Physics Letters, 4 May 2020 (10.1063/5.0004879)

Lingjia Shen et al., MRS Advances,14 April 2021 (10.1557/s43580-021-00051-y)

Matthew Seaberg et al., Physical Review Research, 15 September 2021 (10.1103/PhysRevResearch.3.033249)

Nicolas Burdet et al., Scientific Reports, 30 September 2021 (10.1038/s41598-021-98774-3)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.