Caught on Camera: First Movies of Droplets Getting Blown Up by X-ray Laser

Taken at SLAC, microscopic footage of exploding liquids will give researchers more control over experiments at X-ray lasers.

Researchers have made the first microscopic movies of liquids getting vaporized by the world’s brightest X-ray laser at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. The new data could lead to better and novel experiments at X-ray lasers, whose extremely bright, fast flashes of light take atomic-level snapshots of some of nature’s speediest processes.

“Understanding the dynamics of these explosions will allow us to avoid their unwanted effects on samples,” says Claudiu Stan of Stanford PULSE Institute, a joint institute of Stanford University and SLAC. “It could also help us find new ways of using explosions caused by X-rays to trigger changes in samples and study matter under extreme conditions. These studies could help us better understand a wide range of phenomena in X-ray science and other applications.”

First Look at Liquids Getting Vaporized By the World's Brightest X-ray Laser

Caught on Camera: X-ray Laser Makes a Splash

Liquids are a common way of bringing samples into the path of the X-ray beam for analysis at SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), a DOE Office of Science User Facility, and other X-ray lasers. At full power, ultrabright X-rays can blow up samples within a tiny fraction of a second. Fortunately, in most cases researchers can take the data they need before the damage sets in.

The new study, published today in Nature Physics, shows in microscopic detail how the explosive interaction unfolds and provides clues as to how it could affect X-ray laser experiments.

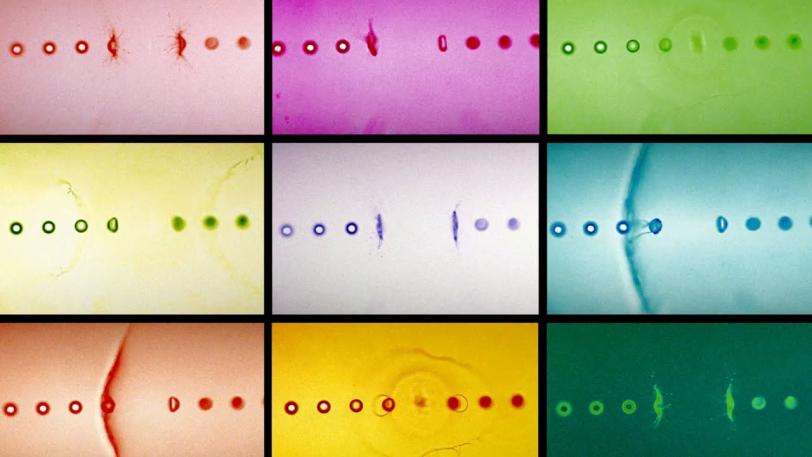

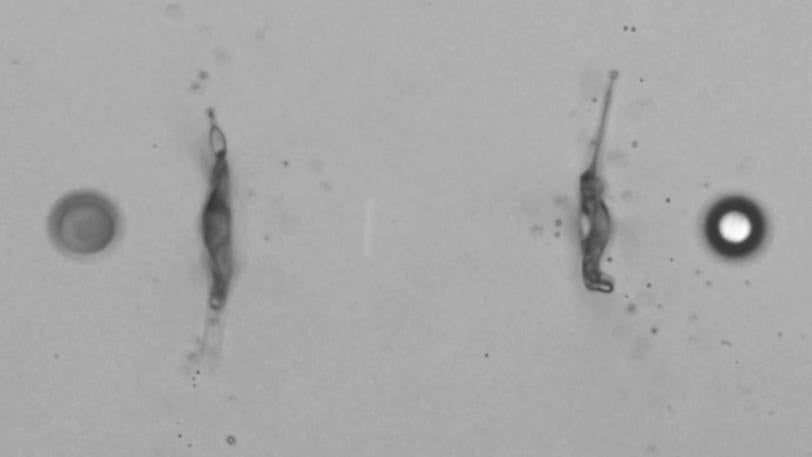

Stan and his team looked at two ways of injecting liquid into the path of the X-ray laser: as a series of individual drops or as a continuous jet. For each X-ray pulse hitting the liquid, the team took one image, timed from five billionths of a second to one ten-thousandth of a second after the pulse. They strung hundreds of these snapshots together into movies.

“Thanks to a special imaging system developed for this purpose, we were able to record these movies for the first time,” says co-author Sébastien Boutet from LCLS. “We used an ultrafast optical laser like a strobe light to illuminate the explosion, and made images with a high-resolution microscope that is suitable for use in the vacuum chamber where the X-rays hit the samples.”

The footage shows how an X-ray pulse rips a drop of liquid apart. This generates a cloud of smaller particles and vapor that expands toward neighboring drops and damages them. These damaged drops then start moving toward the next-nearest drops and merge with them.

LCLS | MEC | Drops Being Vaporized By SLAC's LCLS X-ray Laser

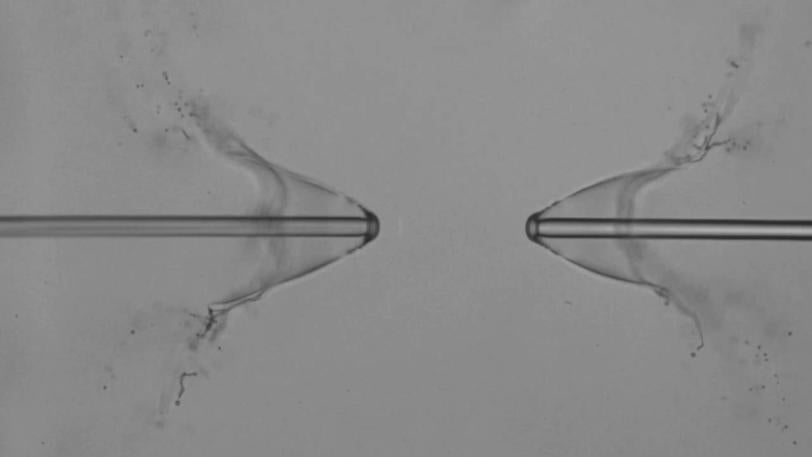

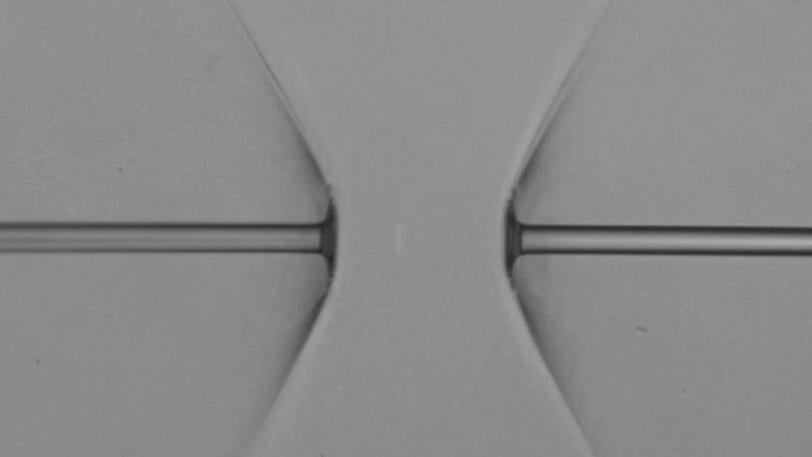

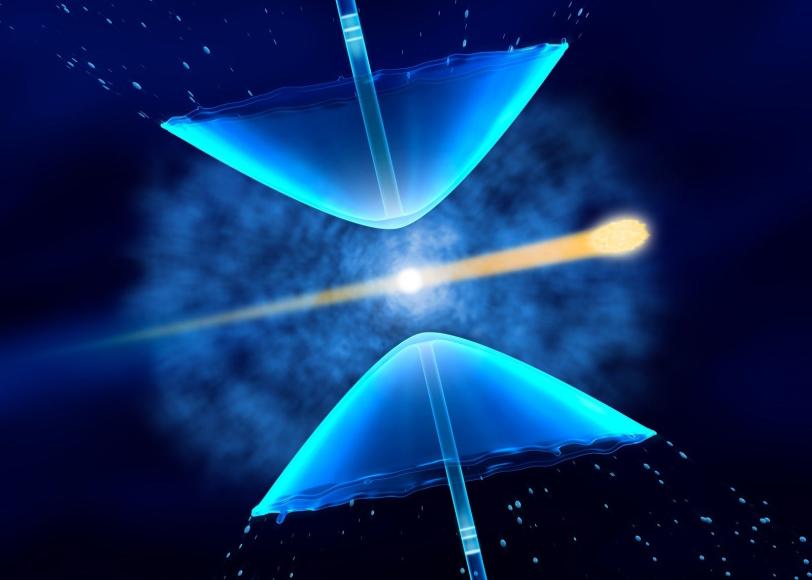

In the case of jets, the movies show how the X-ray pulse initially punches a hole into the stream of liquid. This gap continues to grow, with the ends of the jet on either side of the gap beginning to form a thin liquid film. The film develops an umbrella-like shape, which eventually folds back and merges with the jet.

LCLS | MEC | Liquid Jet Vaporized by SLAC's LCLS X-ray Laser

Predicting Future Challenges and Opportunities

Based on their data, the researchers were able to develop mathematical models that accurately describe the explosive behavior for a number of factors that researchers vary from one LCLS experiment to another, including pulse energy, drop size and jet diameter.

They were also able to predict how gap formation in jets could pose a challenge in experiments at the future light sources European XFEL in Germany and LCLS-II, under construction at SLAC. Both are next-generation X-ray lasers that will fire thousands of times faster than current facilities.

“The jets in our study took up to several millionths of a second to recover from each explosion, so if X-ray pulses come in faster than that, we may not be able to make use of every single pulse for an experiment,” Stan says. “Fortunately, our data show that we can already tune the most commonly used jets in a way that they recover quickly, and there are ways to make them recover even faster. This will allow us to make use of LCLS-II’s full potential.”

The movies also show for the first time how an X-ray blast creates shock waves that rapidly travel through the liquid jet. The team is hopeful that these data could benefit novel experiments, in which shock waves from one X-ray pulse trigger changes in a sample that are probed by a subsequent X-ray pulse. This would open up new avenues for studies of changes in matter that occur at time scales shorter than currently accessible.

Other institutions involved in the study were Max Planck Institute for Medical Research, Germany; Princeton University; and Paul Scherrer Institute, Switzerland. Funding was received from the DOE Office of Science; Max Planck Society; Human Frontiers Science Project; and SLAC’s Laboratory Directed Research & Development program.

LCLS | MEC | Shockwaves In Liquid Jets Caused by SLAC's LCLS X-ray Laser

Citation: C. Stan et al., Nature Physics, 23 May 2016 (10.1038/nphys3779).

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.