Revealed at Last: Atomic Mechanism for Historic Materials Transformation

SLAC-led researchers have made the first direct measurements of a small, extremely rapid atomic rearrangement that dramatically changes the properties of many important materials.

By Mike Ross

SLAC-led researchers have made the first direct measurements of a small and extremely rapid atomic rearrangement, associated with a class called martensitic transformations, that dramatically changes the properties of many important materials, such as doubling the hardness of steel and causing shape-memory alloys to revert to a previous shape.

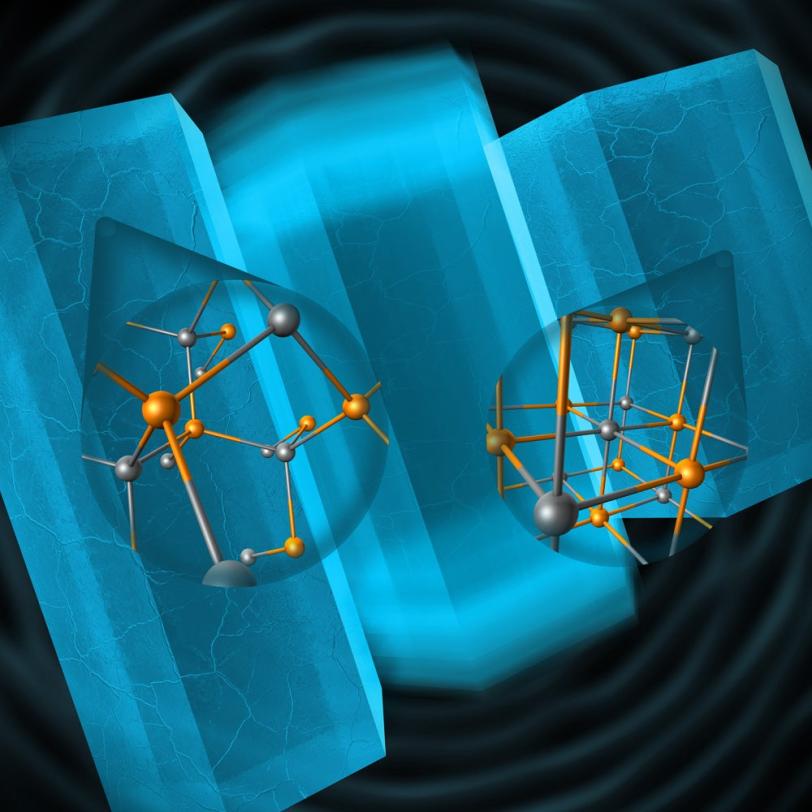

Using high-pressure shock waves and ultrashort X-ray pulses at the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), the researchers observed the details of how this transformation changed the internal atomic structure of a model system, perfect nanocrystals of cadmium sulfide. In the process, they saw for the first time that the nanocrystals pass through a theoretically-predicted intermediate state when undergoing this change.

"To design and engineer new materials with desired properties, we would like to understand the detailed microscopic pathways they follow as they transform," said the team's leader, Aaron Lindenberg, an assistant professor at SLAC and Stanford. "The martensitic transformation is especially important since it occurs in so many important materials. Our technique should ultimately help us see what's happening in other atomic transformations as well."

The team's research results were published last month in Nano Letters.

Named after pioneering German metallurgist Adolf Martens, the martensitic transformation involves collective short-range movements of the atoms in a crystalline solid as it responds to stress. It has been studied for more than 100 years after Martens and colleagues identified that an altered crystalline form in rapidly cooled high-carbon steel was responsible for its enhanced hardness. While the actual atomic movements in martensitic transformations are typically smaller than a nanometer, they can have huge effects on a material’s properties. In addition to hardening steel and facilitating shape-memory alloys, the martensitic transformation underlies such diverse phenomena as geological deformation due to plate tectonics and the mechanism by which invading viruses puncture the walls of cells.

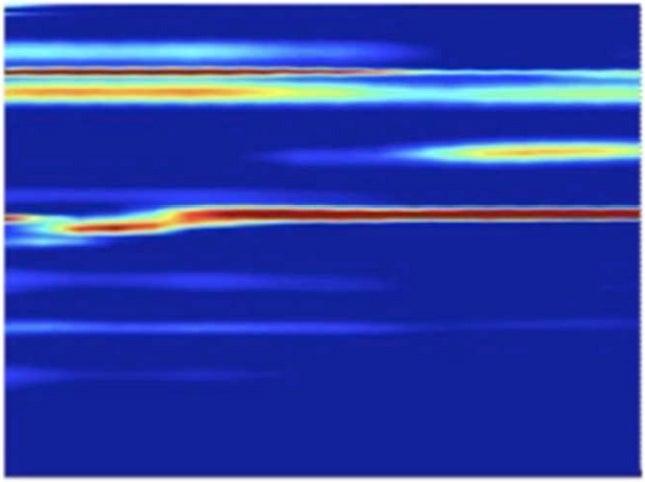

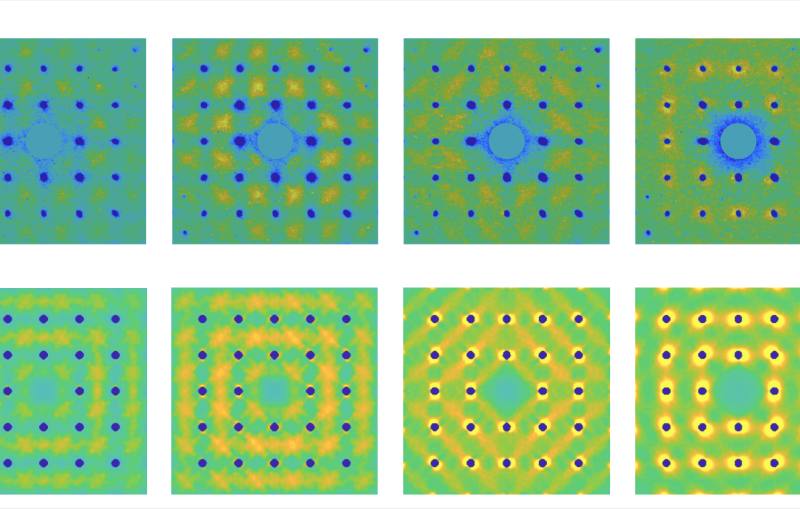

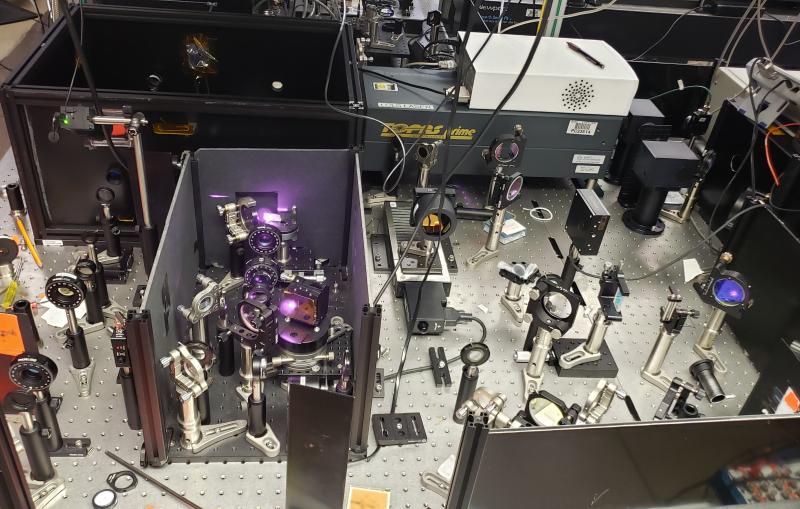

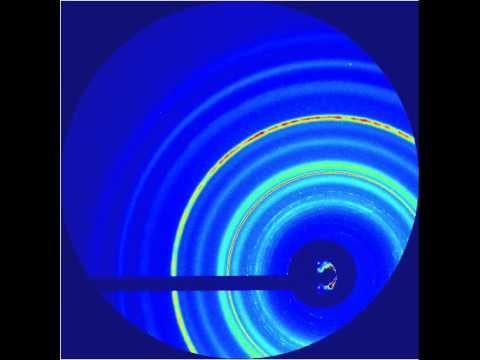

They hit a metal foil with an intense infrared laser pulse, causing it to explode and send a high-pressure shock crashing through the nanocrystals. Pressure from the passing shock wave initiated the transformation. The LCLS X-ray pulses were timed to hit the sample at various split-second times after the shock, producing stop-action X-ray diffraction images that showed the precise positions of the nanocrystal’s atoms during various stages of the transformation, which took only 50 trillionths of a second to complete. The scientists also varied the laser intensity to create shocks of different peak pressures.

Martensite Data

The team found that the transformations caused by the higher-pressure shocks proceeded directly from hexagonal to cubic, while those triggered by the lower-pressure shocks formed a temporary intermediate state. Calculated simulations by other researchers had predicted the intermediate, Lindenberg said. But its absence in the high-pressure case may be an indication that strong shocks act like catalysts, lowering the energy barrier of the transformation so it can proceed directly.

"This set of experiments shows the power of using LCLS, high-power lasers and nanocrystals to examine the rapid atomic rearrangements that are so important in creating materials properties," Lindenberg said. "Until now, there have only been theoretical calculations of how these transformations should occur. Now we can learn firsthand what really happens."

This research was conducted at the X-ray Pump Probe (XPP) experimental station at LCLS. Additional collaborators included researchers from the University of California, Berkeley; Argonne National Laboratory in Illinois; and the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany. The researchers acknowledge funding from the DOE Office of Science and the German Research Council.

Citation: Joshua S. Wittenberg et al, Nano Letters, DOI: 10.1021/nl500043c

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, California, SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science.

SLAC’s LCLS is the world’s most powerful X-ray free-electron laser. A DOE Office of Science national user facility, its highly focused beam shines a billion times brighter than previous X-ray sources to shed light on fundamental processes of chemistry, materials and energy science, technology and life itself. For more information, visit lcls.slac.stanford.edu.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.