Imaging of tiny particles at SLAC’s X-ray laser just got faster

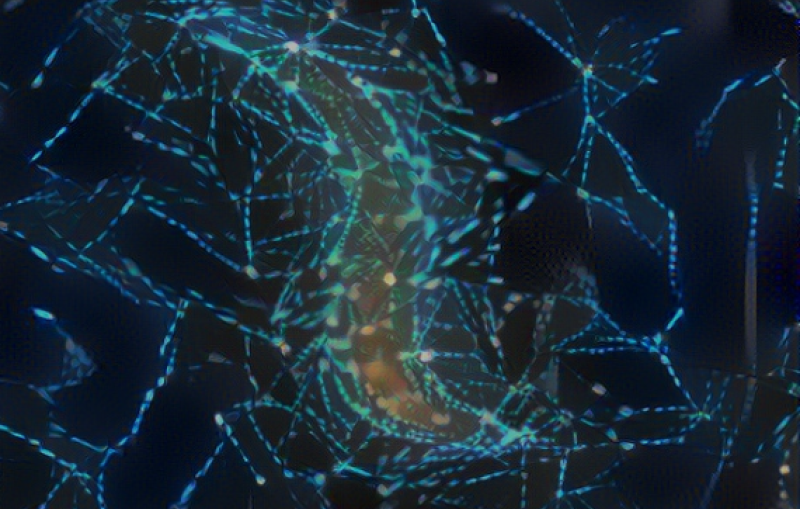

A new machine learning algorithm rapidly reconstructs 3D images from X-ray data.

By Ula Chrobak

Key takeaways

- A new machine learning algorithm speeds up the reconstruction of 3D images from data taken with SLAC's LCLS X-ray laser.

- Called X-RAI, the tool looks at millions of X-ray images to create the 3D reconstruction of target particles.

- The method may help researchers create movies of proteins and viruses better and faster than before.

Soon, researchers may be able to create movies of their favorite protein or virus better and faster than ever before.

Researchers at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have pioneered a new machine learning method – called X-RAI (X-Ray single particle imaging with Amortized Inference) – that can “look” at millions of X-ray laser-generated images and create a three-dimensional reconstruction of the target particle. The team recently reported their findings in Nature Communications.

X-RAI’s ability to sort through a massive number of images and learn as it goes could unlock limits in data-gathering, allowing researchers to see molecules up close – and perhaps even on the move. “There is really no limit” to the dataset size it can handle, said SLAC staff scientist Frédéric Poitevin, one of the study’s principal investigators.

Lagging algorithms

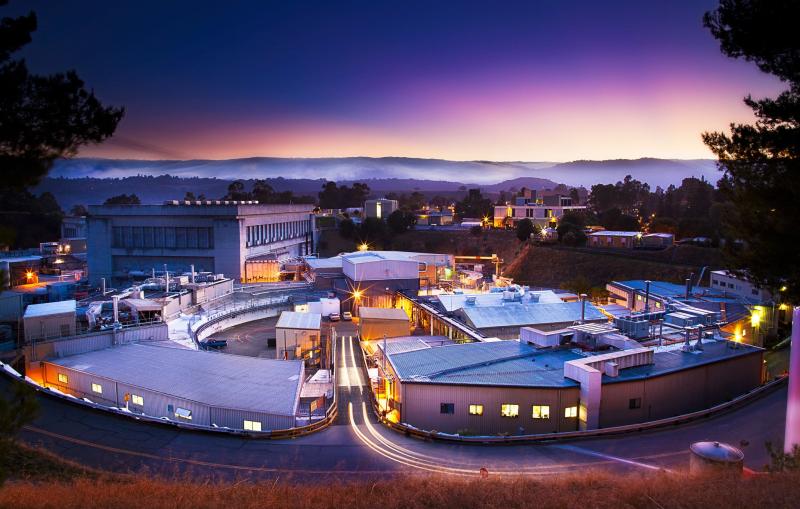

Linac Coherent Light Source

The Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) at SLAC takes X-ray snapshots of atoms and molecules at work, revealing fundamental processes in materials, technology and living things.

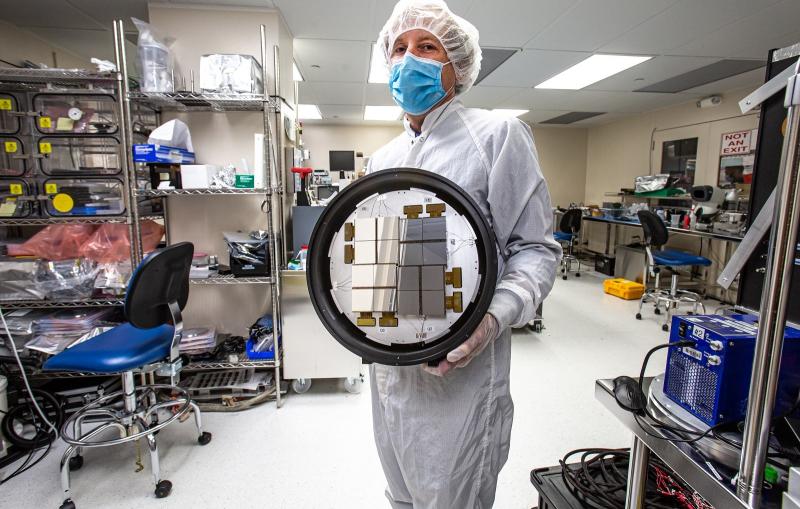

The work took place at SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) – the world’s most powerful X-ray free-electron laser, where researchers blast samples with X-ray pulses just a few millionths of a billionth of a second long to gain insights into the structures and motions of molecules, such as proteins or viruses.

When researchers send these pulses through a sample, the X-rays scatter off the molecules in that sample and create a 2D scattering image on a detector. By combining many of those 2D images, capturing information about the molecules at many different angles, the researchers can reconstruct the molecules’ 3D structure.

But this process is a time-consuming task, requiring hundreds of thousands to millions of 2D images. On top of that, the algorithms traditionally used to piece scattering images together get slower as X-ray laser data pile up. For each snapshot, the algorithms try to predict the object’s 3D structure – the more snapshots, the more time spent puzzling over the reconstruction.

Such computing delays can limit researchers at LCLS, who may only have a few days of access to the facility to run a whole suite of experiments. “How could we make this faster to the point that we could actually do the reconstruction as we collect the data and not wait hours or days for the results?” asked Poitevin.

Unlocking LCLS datasets

Taming big data and particle beams: how SLAC researchers are pushing AI to the edge

Read how SLAC researchers collaborate to develop AI tools to make molecular movies, speeding up the discovery process in the era of big data.

To solve this problem, Poitevin and colleagues, including Gordon Wetzstein's lab at Stanford University, developed a new machine learning program that processes X-ray laser data on the fly – and improves as it proceeds.

The neural network “looks” at the 2D images and predicts a 3D orientation of the sample particle. It also works in the opposite direction, taking a 3D projection and generating 2D images from it. This bidirectional process allows for the AI to continually refine the relationship between the 2D X-ray laser data and the 3D reconstruction. The more data, the better it understands the relationship between the 2D images and 3D structure, becoming more efficient.

For large datasets, X-RAI is “much faster” than other programs, said Jay Shenoy, the study’s first author and a Stanford PhD student in computer science. In the paper, the team demonstrated the new algorithm could process up to 160 images per second in real time while predicting the object’s 3D structure on the computer screen. The researchers also compared how well X-RAI reconstructed the 3D structure of two biomolecules – a ribosomal subunit and the protein ATP synthase – compared to two other algorithms and found that the new program produced reconstructions that were sharper.

The team hopes the advance will enable users to make the most of their time at LCLS and other X-ray lasers around the world. Experimental time at this cutting-edge X-ray light source is highly competitive, and successful applicants are only granted a few days of access at a time. X-RAI could help researchers get more out of the allocated time.

Opening the door to a speedy analysis of near-limitless amounts of data may also help researchers to study particles in motion. With enough images, they could reconstruct a movie of, for example, an enzyme interacting with a drug. With the improvements to X-ray imaging, “you might be able to actually get a more accurate picture of how your molecule moves,” said Poitevin.

Large parts of this work were funded by the Department of Energy Office of Science Basic Energy Sciences program, the Laboratory Directed Research and Development (LDRD) Program at SLAC and the National Science Foundation. LCLS is an Office of Science user facility.

Citation: J. Shenoy et al., Nature Communications, 24 July 2025 (10.1038/ s41467-025-62226-7)

For media inquiries, please contact media@slac.stanford.edu. For other questions or comments, contact SLAC Strategic Communications & External Affairs at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.