SLAC scientists created the most powerful ultrashort electron beam in the world

Researchers carefully positioned lasers to compress billions of electrons together, creating a beam five times more powerful than ever before.

By Kimberly Hickok

Scientists have created an ultrashort electron beam with five times more peak current than any other similar beam on Earth.

Described in a paper published in Physical Review Letters, this achievement addresses one of the grand challenges of particle accelerator and beam physics and opens the door for new discoveries in a broad realm of scientific fields, including quantum chemistry, astrophysics, and material science.

“Not only can we create such a powerful electron beam, but we’re also able to control the beam in ways that are customizable and on demand, which means we can probe a much wider range of physical and chemical phenomena than ever before,” said Claudio Emma, a staff scientist at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, who is a researcher at SLAC’s Facility for Advanced Accelerator Experimental Tests (FACET-II) and a lead author on the new study.

The power balance

As outlined in the Accelerator and Beam Physics Roadmap published in 2022, one of the biggest challenges for physicists – until now – has been to produce electron beams that are vastly more powerful while also preserving beam quality.

Traditionally, a microwave field is used to compress and focus the electron beam. The electrons within the field are staggered, so that those further back have more energy than those in the front. It’s sort of like runners staggered at the start of a track race, Emma explained. “We then send them around a bend, so the electrons in back catch up with electrons in front, and then at the end, you have a bunch of electrons together in a focused beam.”

The problem with this approach is that as they accelerate, electrons emit radiation and lose energy, so the quality of the beam deteriorates. That creates a tradeoff between beam energy and quality. “We can't apply traditional methods to compress bunches of electrons at the submicron scale, while also preserving beam quality,” Emma said.

Lasers for the win

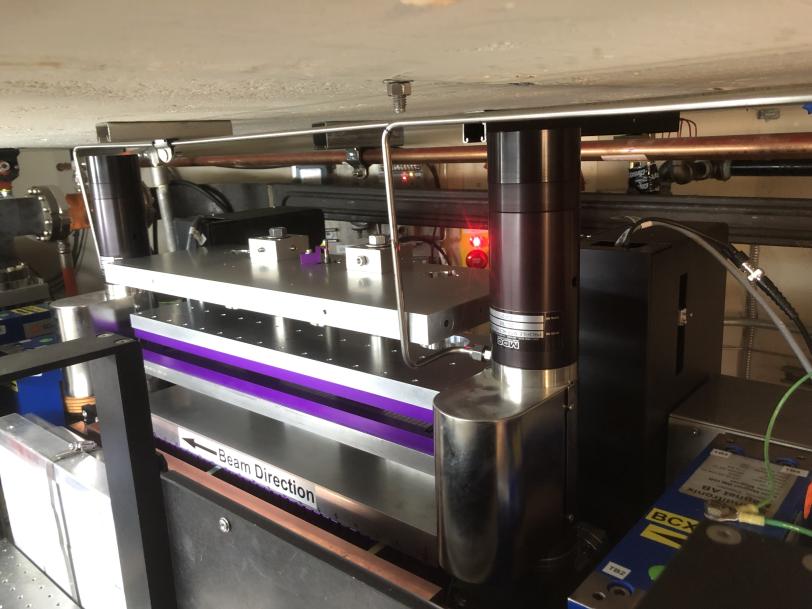

To solve this issue, SLAC researchers compressed billions of electrons into a length less than one micrometer using a laser-based shaping technique originally developed for X-ray free-electron lasers, such as SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS). “The big advantage of using a laser is that we can apply an energy modulation that's much more precise than what we can do with microwave fields,” Emma said.

But it’s not as simple as just shooting a few lasers down a tunnel. “We have a one-kilometer-long machine, and the laser interacts with the beam in the first 10 meters, so you have to get the shaping exactly right, then you have to transport the beam for another kilometer without losing this modulation, and you have to compress it,” Emma said. “So it wasn't easy.”

After several months of testing and finessing their laser shaping technique, Emma and his team can now repeatedly produce high energy, femtosecond-duration, petawatt peak power electron beams that are about five times higher in current than what could previously be achieved.

An incredible new tool

This new beam will allow scientists to probe a whole series of natural phenomena, including testing hypotheses in quantum physics, materials science, and astrophysics.

In astrophysics, for example, this beam can be directed to a solid or gas target to create a filament similar to those seen in stars. “Scientists know that these filaments occur, but now we can test how they occur and evolve in the lab with a level of power we haven’t had before,” Emma said.

Fellow FACET-II researchers pounced on the more powerful beam and have already applied it to advancing plasma wakefield technology. Emma is particularly excited about the prospect of further compressing these beams to make attosecond light pulses, further enhancing LCLS’s current attosecond capabilities and driving even more pioneering science. “If you have the beam as a fast camera, then you also have a light pulse that's very short, and now suddenly you have two complementary probes,” Emma explained. “That’s a unique capability and we can do a lot of things with that.”

Emma and his colleagues are excited about the prospects this new electron beam will bring. “We have a really exciting and interesting facility at FACET-II where people can come and do their experiments,” he said. “If you need an extreme beam, we have the tool for you, and let’s work together.”

The research was supported by the DOE Office of Science. FACET-II and LCLS are DOE Office of Science user facilities.

Citation: Claudio Emma et al., Physical Review Letters, 27 February 2025 (10.1103/PhysRevLett.134.085001)

For questions or comments, contact SLAC Strategic Communications & External Affairs at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.