Exploring the ultrasmall and ultrafast through advances in attosecond science

Researchers developed new methods that produce intense attosecond pulses and pulse pairs to gain insights into the fastest motions inside atoms and molecules. It could lead to advancements in fields ranging from chemistry to materials science.

A team of scientists at the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory are developing new methods to probe the universe’s minute details at extraordinary speeds.

In previous research, the researchers developed a way to produce X-ray laser bursts which are several hundred attoseconds (or billionths of a billionth of a second) long. This method, called X-ray laser-enhanced attosecond pulse generation (XLEAP), allows scientists to investigate how electrons zipping around molecules jumpstart key processes in biology, chemistry, materials science and more.

Congratulations!

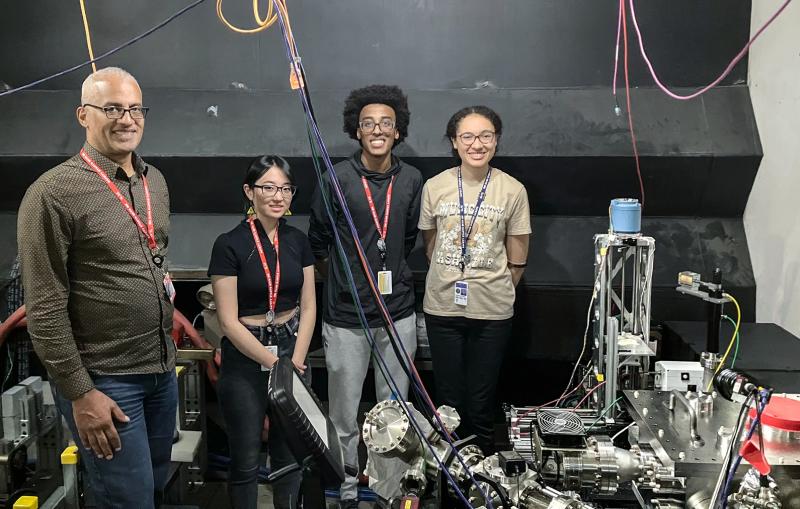

Two of our extraordinary researchers, Agostino Marinelli and Gennady Stupakov, won the prestigious 2024 Particle Accelerator Science and Technology Award. Each year, the IEEE Nuclear & Plasma Sciences Society provides the award to individuals who have made outstanding contributions to the development of particle accelerator science and technology.

Marinelli has made critical contributions to the development and operation of attosecond X-ray free-electron lasers. He is currently the head of SLAC’s free-electron laser physics department and the co-lead of the free-electron laser R&D program at the lab.

Stupakov has made broad contributions in accelerator science, including innovative advances to free-electron lasers, enabling their robust operation and extended performance. His most recent research has been focused on beam dynamics in free electron lasers, collective effects in accelerators, and coherent electron cooling in hadron colliders.

SLAC operates one of the world’s most powerful X-ray free electron lasers in the world, which takes snapshots of atoms and molecules at work. This allows researchers to explore ultrafast phenomena that are key to a broad range of applications, from quantum materials to clean energy technologies and medicine. Being able to create attosecond X-ray flashes opens up a new window to some of the fastest processes in nature.

But how fast exactly is an attosecond? To put things in perspective: There are as many of them in a single second as there are seconds in half the age of the universe!

Now, led by SLAC scientists Agostino Marinelli and James Cryan, the team has developed new tools to use these attosecond pulses in groundbreaking ways: the first use of attosecond pulses in pump-probe experiments and the production of the most powerful attosecond X-ray pulses ever reported. The experiments, conducted at SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray free-electron laser and published in two articles in Nature Photonics, could revolutionize fields ranging from chemistry to materials science by offering insights into the fastest motions inside atoms and molecules.

A new method for measuring ultrafast phenomena

In the first development, researchers introduced a novel approach to conducting "pump-probe" experiments with attosecond X-ray pulses. These experiments, aimed at measuring ultrafast events shorter than a trillionth of a second, involve exciting atoms with a "pump" pulse followed by probing them with a second pulse to observe resultant changes.

This technique allowed scientists to track and measure electron movement within atoms and molecules – a critical process influencing chemical reactions, material properties, and biological functions. They accomplished this by generating pairs of laser pulses in two colors and meticulously controlling the delay between them to as little as 270 attoseconds.

"This capability unlocks new opportunities for studying the interaction of light with matter at the most fundamental level," Cryan said. "It's thrilling because it has evolved into a practical tool, enabling us to see electron dynamics that were once out of our reach. We’re now observing processes that occur on timescales approaching the time it takes light to cross a molecule."

In a recent paper, researchers used this technique to observe electrons moving in real-time in liquid water. Future studies will apply this method to various molecular systems, refining these measurements' accuracy and expanding their application across scientific disciplines.

Creating high-power attosecond pulses

The second development concentrated on generating high-power attosecond pulses using a technique known as "super-radiance," achieving power levels of nearly one terawatt. This process involved a cascading effect in an X-ray free-electron laser, significantly amplifying the pulses’ power.

The heightened intensity of these pulses allows scientists to explore unique states of matter and witness phenomena occurring at even shorter time scales.

"These are the most powerful attosecond X-ray pulses ever reported. The intensity of these pulses allows us to explore entirely new regimes of X-ray science," Marinelli said. "We’ve pushed the boundaries of the X-ray pulse energy, reaching power levels that open new experimental realms. This result was achieved thanks to a special type of wave that maintains its shape and speed as it propagates through the electron bunch, dramatically enhancing the intensity and energy of our pulses."

The researchers plan to further refine this technology to enhance the stability and control of these high-power pulses, aiming to widen their application across diverse scientific areas.

Propelling scientific exploration forward

These developments push the boundaries of our observational and measurement capabilities, setting the stage for future scientific breakthroughs that could transform our understanding of the natural world.

Observing atoms and electrons in motion facilitates the design of new materials with tailored properties for technology, energy, and other fields. Understanding electron movement during chemical reactions can also facilitate intelligent chemical design principles.

"These studies not only deepen our understanding of physics but also pave the way for future innovations that could transform our understanding electron driven processes," Cryan said. "Each attosecond pulse we generate offers a new glimpse at nature's building blocks, unveiling dynamics previously concealed from view. We anticipate many more exciting discoveries ahead."

LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility. This research was supported by the Office of Science.

Citations: Z. Guo et al., Nature Photonics, 11 April 2024 (doi.org/10.1038/s41566-024-01419-w)

P. Franz et al., Nature Photonics, 13 May 2024 (doi.org/10.1038/s41566-024-01427-w)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.