Researchers catch protons in the act of dissociation with SLAC’s ultrafast 'electron camera'

Proving the technique works puts scientists one step closer to unraveling the mysteries of hydrogen transfers.

By Elise Overgaard

Scientists have caught fast-moving hydrogen atoms – the keys to countless biological and chemical reactions – in action.

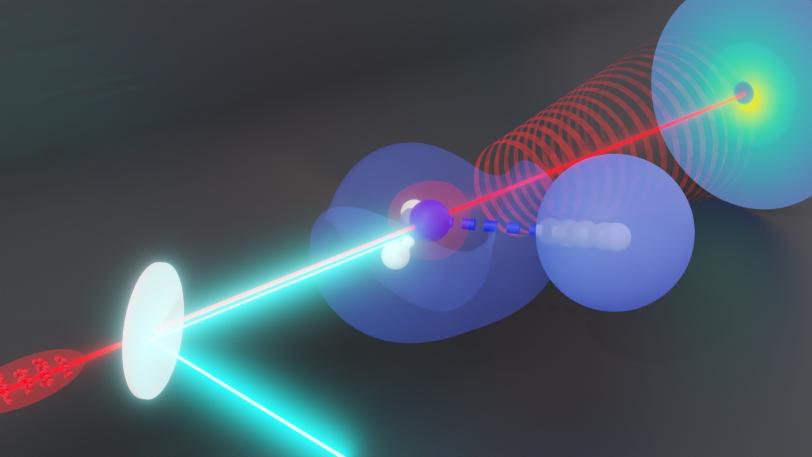

A team led by researchers at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University used ultrafast electron diffraction (UED) to record the motion of hydrogen atoms within ammonia molecules. Others had theorized they could track hydrogen atoms with electron diffraction, but until now nobody had done the experiment successfully.

The results, published October 5 in Physical Review Letters, leverage the strengths of high-energy Megaelectronvolt (MeV) electrons for studying hydrogen atoms and proton transfers, in which the singular proton that makes up the nucleus of a hydrogen atom moves from one molecule to another.

Proton transfers drive countless reactions in biology and chemistry – think enzymes, which help catalyze biochemical reactions, and proton pumps, which are essential to mitochondria, the powerhouses of cells – so it would be helpful to know exactly how its structure evolves during those reactions. But proton transfers happen super-fast – within a few femtoseconds, one millionth of one billionth of one second. It’s challenging to catch them in action.

One possibility is to shoot X-rays at a molecule, then use the scattered X-rays to learn about the molecule’s structure as it evolves. Alas, X-rays only interact with electrons – not atomic nuclei – so it’s not the most sensitive method.

To get to the answers they were looking for, a team led by SLAC scientist Thomas Wolf, put MeV-UED, SLAC's ultrafast electron diffraction camera to work. They used gas-phase ammonia, which has three hydrogen atoms attached to a nitrogen atom. The team struck ammonia with ultraviolet light, dissociating, or breaking, one of the hydrogen-nitrogen bonds, then fired a beam of electrons through it and captured the diffracted electrons.

Not only did they catch signals from the hydrogen separating from the nitrogen nucleus, they also caught the associated change in the structure of the molecule. What’s more, the scattered electrons shot off at different angles, so they could separate the two signals.

“Having something that’s sensitive to the electrons and something that’s sensitive to the nuclei in the same experiment is extremely useful,” Wolf said. “If we can see what happens first when an atom dissociates – whether the nuclei or the electrons make the first move to separate – we can answer questions about how dissociation reactions happen.”

With that information, scientists could close in on the elusive mechanism of proton transfer, which could help to answer myriad questions in chemistry and biology. Knowing what protons are doing could have important implications in structural biology, where traditional methods like X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy have difficulty “seeing” protons.

In the future the group will do the same experiment using X-rays at SLAC’s X-ray laser, the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), to see just how different the results are. They also hope to up the intensity of the electron beam and improve the time resolution of the experiment so that they can actually resolve individual steps of proton dissociation over time.

The research was funded in part by the DOE Office of Science. MeV-UED is an instrument of SLAC’s LCLS X-ray laser facility. LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

Citation: Elio Champenois et al., Physical Review Letters, 5 Oct 2023 (10.1103/PhysRevLett.131.143001)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.