New collaboration aims to bring cutting-edge X-ray methods to more biological researchers

SSRL and LCLS scientists will help visiting research teams solve their experimental challenges, then apply what they’ve learned to help others work more efficiently.

Although synchrotron and X-ray free electron laser light sources have become some of the most valuable tools for studying biomolecular structure, they face many challenges – among them, the fact that X-rays can easily destroy proteins and other biological samples before scientists can get a good look at them.

It's a familiar story for researchers like Guillermo Calero, a structural biologist at the University of Pittsburgh who studies RNA polymerases, essential enzymes that read DNA and synthesize RNA as part of a process called transcription. While researchers knew a significant amount about the structure of human polymerases, the limitations of X-ray methods have hindered efforts to get a detailed picture of key parts of these structures, metals that catalyze biological reactions, or understand how they change during transcription.

Now, cases like Calero’s are driving a new, National Institutes of Health-funded effort at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory to enable X-ray biomedical experiments that might not otherwise have been possible, make experiments more efficient, and ultimately to open up more opportunities for bioscientists to make use of the lab’s cutting-edge tools.

“The project will allow scientists to do structural biology experiments that are extremely difficult or impossible to perform at other facilities,” said Aina Cohen, a senior scientist at SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) who will lead the new effort with Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) staff scientists Mark Hunter and Sébastien Boutet. “These experiments will facilitate paradigm-shifting advances on a wide variety of topics in biomedicine.”

Biological challenges

Situations like Calero’s highlight many of the problems that come up in studying biomolecules, Cohen said. For one thing, LCLS’s short, bright X-ray pulses can capture images of polymerase and related enzymes in crystal form before destroying them, but to do that well, researchers need to view multiple positions on larger crystals – or a whole lot of smaller crystals – which has proven especially challenging.

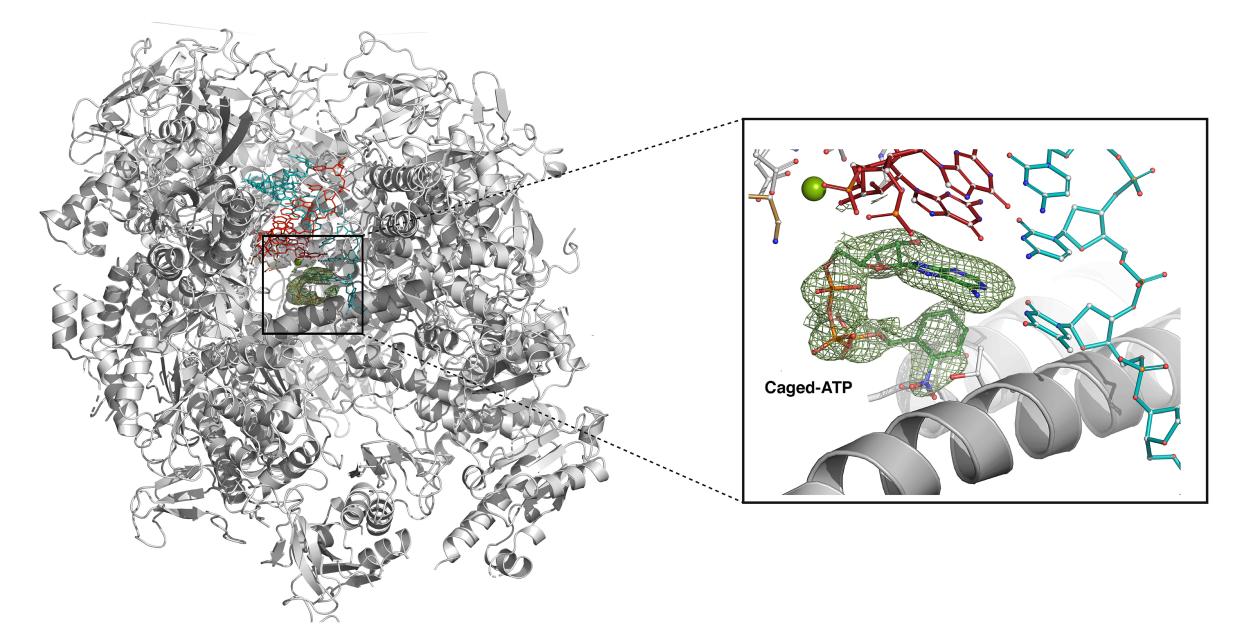

After considerable efforts to study polymerase at the synchrotron, Calero and his team eventually produced the highest-resolution images ever obtained for one kind of polymerase, RNA-polymerase-II, at LCLS with the help of SLAC scientists. They then tackled a new challenge: seeing how the structure of polymerase changes during the transcription process, and doing this at higher, more physiologically relevant temperatures.

“These samples are almost like a brittle Jell-O,” Cohen said, “and painfully sensitive to heat, movement and chemical contamination,” so the team had to figure out a gentler way to deliver them to the beamline for these higher-temperature studies.

Collaborating for solutions

To address the problem, Calero and his SLAC collaborators designed a system that allows them to trigger the transcription process inside RNA polymerase II crystals with ultraviolet light, observing the changes in the molecules in the crystals with X-rays. The team has already run some initial experiments at SSRL – all remotely, Cohen said – that show how transcription progresses. As part of the new NIH-funded project, they will also conduct experiments with improved technologies at LCLS, where they can observe shorter timescales in the molecular equivalent of a high-speed camera.

Calero’s work is just one example of the kinds of research the project will enable. For instance, the new effort will also help researchers like Marius Schmidt, a biophysicist at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee who studies the mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in bacteria. By improving technologies that shoot a stream of crystals into an X-ray beam, scientists like Schmidt will be better able to study how biological reactions unfold on-the-fly.

Eventually, SSRL and LCLS want to bring such advances to more researchers, and right now this work is often customized experiment by experiment, Boutet said. “The overall goal is to try to streamline and automate biological experiments,” he said. “We do too much basically by hand.”

Hunter agreed: “Right now, we just empirically figure it out each time, and we need much more rigor,” he said. “We want to take the art of doing this thing and turn it into a quantified science.”

To do so, the team is starting from a “testbed” of specific biomedical projects, including Calero’s, Schmidt’s and seven others, Boutet said. In collaboration with groups of SSRL and LCLS users, the SLAC researchers will work to develop more consistent, optimized methods for everything from protein crystallization and sample storage to sample delivery into the X-ray beam and software development for automated data analysis. They will also work on automating advanced experiments to study short-lived intermediate structures and try to integrate complementary methods to make the overall experimental process smoother. Putting all these pieces together will improve the efficiency of these experiments, freeing up more time to do cutting-edge research and allowing a broader access to the unique lightsource capabilities of SLAC.

“It’s trying to build a solid foundation for supporting users, so that any lab could come and make use of LCLS and SSRL,” Hunter said.

The research is funded in part by a Biomedical Technology Research Resource grant from the National Institutes of Health. The Structural Molecular Biology Program at SSRL is supported by the DOE Office of Science and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences. SSRL and LCLS are DOE Office of Science user facilities.

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.