What is a molecular movie?

Molecular movie-making is both an art and a science; the results let us watch how nature works on the smallest scales.

By Andy Freeberg

One of modern science’s most important quests is to understand how the world works at the tiniest and fastest scales – the realm of atoms and molecules. Until a few years ago, all we had were static pictures of this world. But today scientists can make “movies” of molecules moving, bending and busting apart.

What does it really mean to make a molecular movie? What kinds of movies are scientists making and why? Read on to find out what’s happening on science’s small screen.

Moviemaking at its smallest

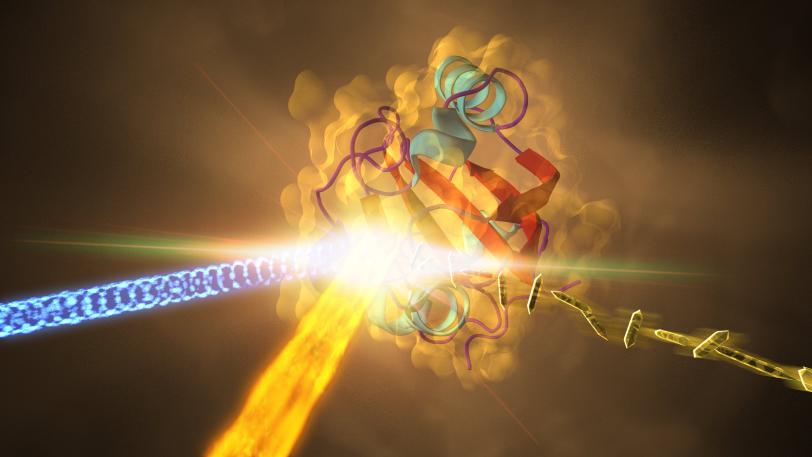

The basic idea is simple: Shoot a series of images of a molecule, at extremely high resolution, within just a few quadrillionths of a second of each other, and then string them together like frames from a film into a movie that shows how the molecule moves and changes over time.

Making a molecular movie: how it works

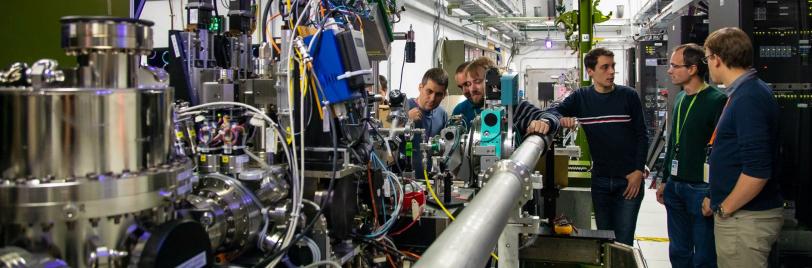

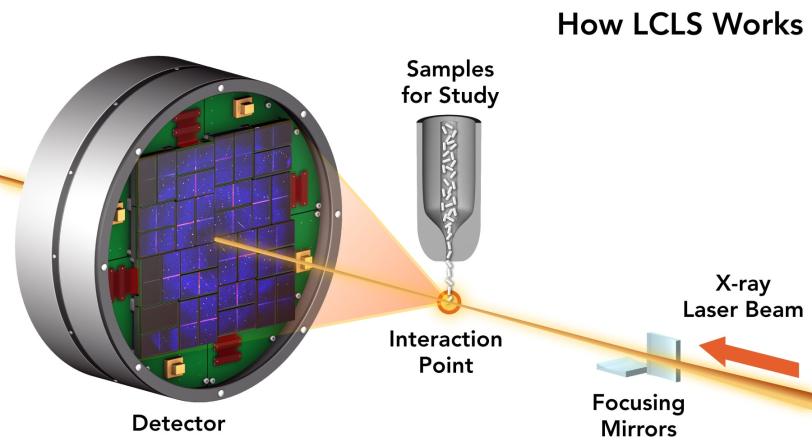

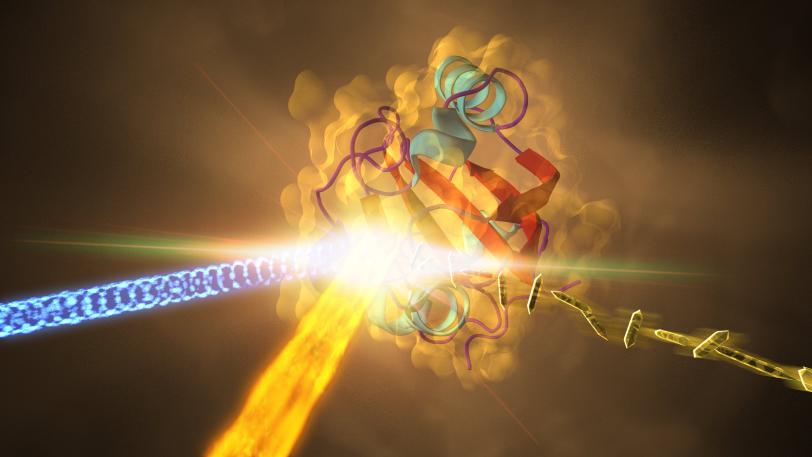

To do this you need a very specialized camera. At the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory we have two of them: the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), which shoots movies with brilliant pulses of X-ray laser light, and an “electron camera” known as MeV-UED that shoots them with intense pulses of electrons, a technique called ultrafast electron diffraction.

‘High definition’ isn’t nearly high enough.

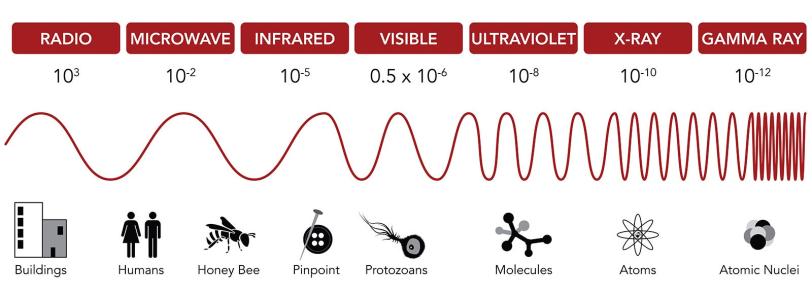

Regular movies capture visible light bouncing off objects in a scene. But molecules are much smaller than everyday objects, so you need a camera that operates with much shorter wavelengths of light.

Molecules are measured in angstroms. An angstrom is the width of a single hydrogen atom, a ten-billionth of a meter. If you were to shrink to the size of an atom, a trip across the room would be the rough equivalent of a trip to Mars.

Conveniently, there are wavelengths of light that match the molecular scale: X-rays. So X-ray light is a general requirement for molecular movie cameras.

Alternatively, an energetic beam of electrons, with its own unique imaging properties and challenges, can be used to shoot molecular movies. Although we tend to think of electrons as particles, they also behave as waves, and the energetic electron beam from UED has a wavelength similar to X-rays.

Without any camera lenses, molecular movies rely on coherent waves to tell a coherent story.

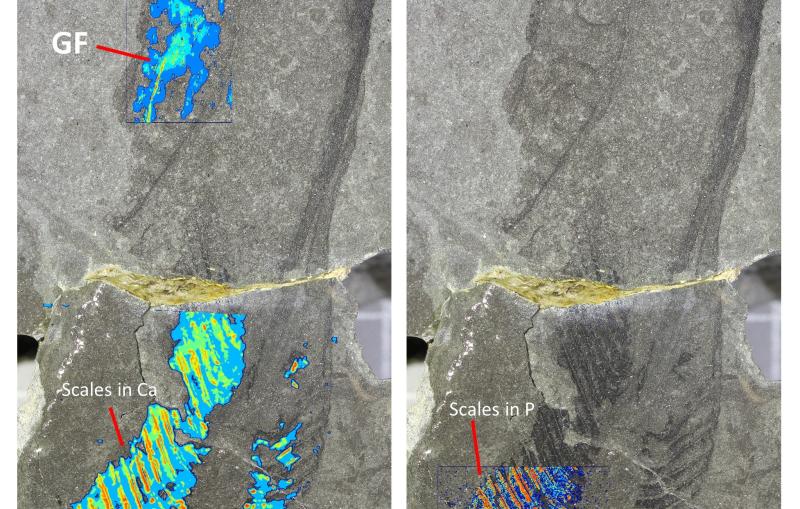

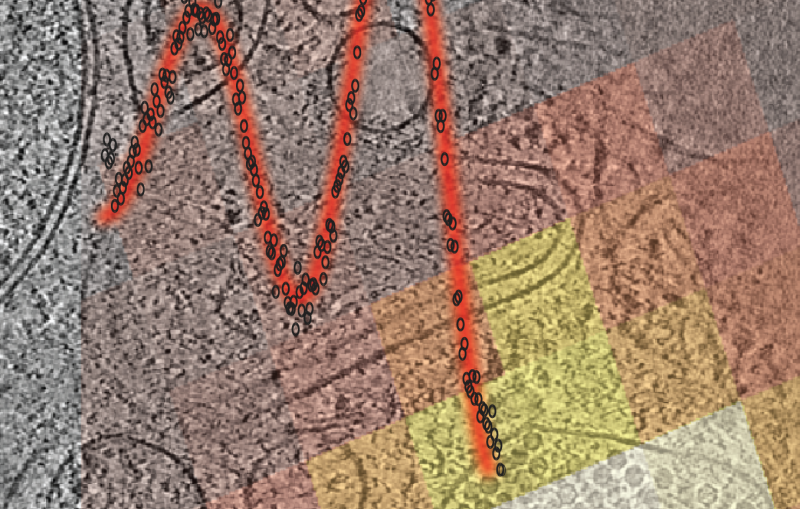

Frames of a molecular movie aren’t photographs. Each electron or particle of light that’s beamed through a sample penetrates some components and ricochets off others. Tiny, uncharged photons of X-ray light are deflected by the electron shells around an atom, while energetic electrons make it all the way to the nucleus before bouncing away.

Critically, the X-rays that come from LCLS arrive in a neat and orderly stream of a particular wavelength, which is what makes LCLS a laser. That “coherence” means when the waves start to interfere with one another, it’s possible to catch the resulting scatters and reconstruct them into 2D or 3D pictures with the help of extensive computer modeling.

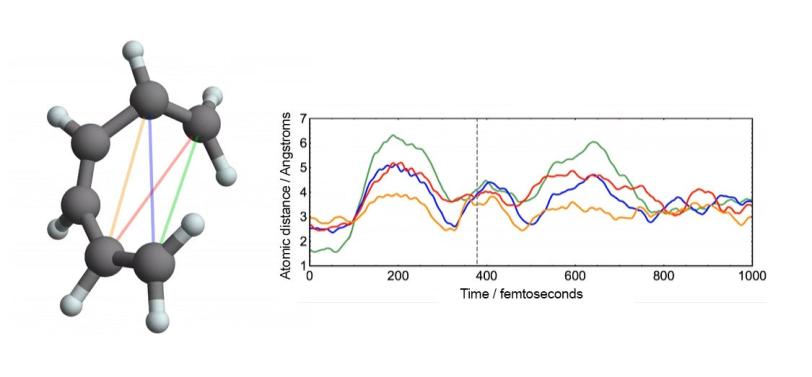

With the advancement of these coherent imaging techniques, the best molecular movies can now feature a much wider variety of samples and resolve details as small as tenths or hundredths of angstroms. At that scale the world is as much nothing as something, and measuring a molecule’s nuclei, electrons and chemical bonds is more about gauging their positions relative to each other than their absolute positions in space.

The world at atomic scales is a frenzy of motion that requires an extremely short shutter speed.

To get a crisp handheld photo you need a shutter speed of roughly 8 milliseconds (0.008 seconds). High-speed photography capable of freezing a speeding bullet use strobes around a microsecond long (0.000001 seconds). Capturing a sharp image of a molecule in motion requires a shutter speed on the order of one femtosecond, a quadrillionth of a second (0.000000000000001 seconds).

What is a Femtosecond?

A few femtoseconds is just fast enough to see atoms exchange electrons and chemical bonds twist, break or even form. New technology that’s on the verge of reaching attosecond resolution (add three more zeros to the right of the decimal point) should yield even more detail.

A movie needs action. Most molecular movies start with a laser blast.

The idea is to kick off some molecular action in a precise and controlled way, and then measure the molecule’s response – changes in the relative positions of its atoms – at closely spaced intervals.

While it’s possible to start the initial action with temperature, chemistry, magnetism or electric fields, none of these offer as precise control over the timing of the trigger as a quick blast of light. Therefore, an optical laser pulse is the favorite trigger for the vast majority of experiments.

At the speed of molecules, some processes are easier to film than others. Scientists often have a good understanding of how a molecule looks at the beginning and end of a reaction, but not of what happens in between. In some cases a molecule may go down more than one path leading to different end points, and why that happens is a mystery.

Just like in Hollywood, not all molecules are destined for stardom.

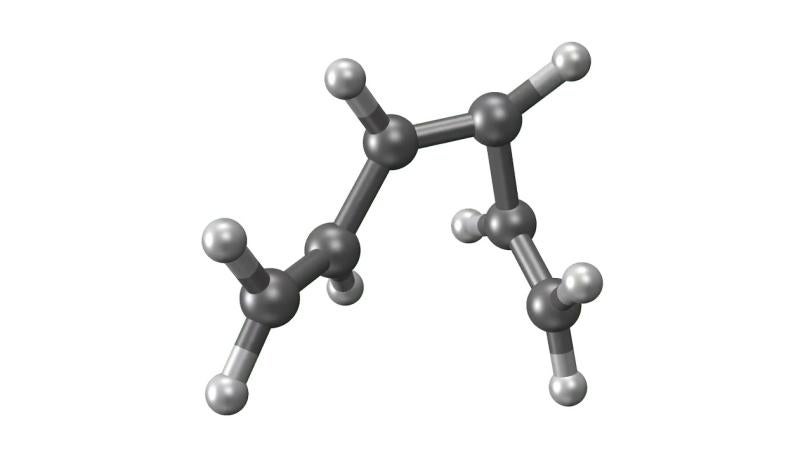

With techniques still in their early days, scientists favor certain kinds of subjects to put on film. One key feature of a good molecular actor is simplicity. The best candidates have enough atoms and bonds to be interesting, but not enough to become overwhelming. Many early movies have focused on simple gases of elements like nitrogen and iodine.

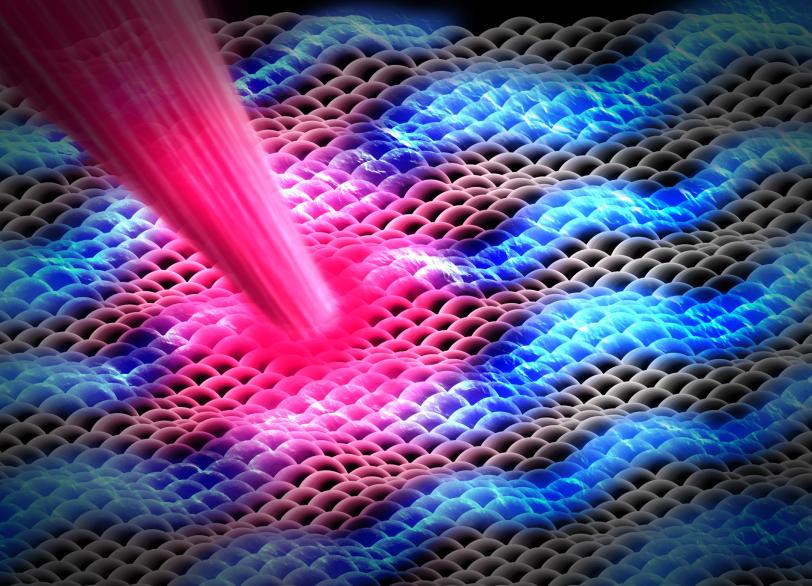

Another key to simplicity is to record well-organized molecules like those in exotic 2D materials, single-layer patterns of atoms that ripple and wave like a sheet in the wind when struck by a laser.

Perhaps the most bankable stars of early molecular movies are model systems – molecules that are already well-studied and understood. Among these are a hoop of six carbon atoms called cyclohexadiene and the muscle protein myoglobin. The outsized wealth of information on these celebrity molecules helps prove the validity of the new data, and seeing them in a new light through molecular movies sometimes yields surprises.

LCLS | UED | Molecular Movie

Molecules that respond to light are prime candidates.

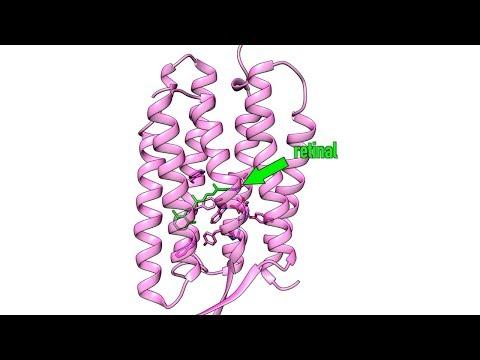

A protein complex called photosystem II that is key to converting sunlight to energy in photosynthesis is a prominent example, but rhodopsin, photolyase, retinal and photoactive yellow protein are other strong characters in the biological genre. Not only do they help us understand the mechanics of life, but many of them also offer potential pathways to new and better medical treatments.

The First Molecular Movie of One of Nature’s Most Widely Used Light Sensors

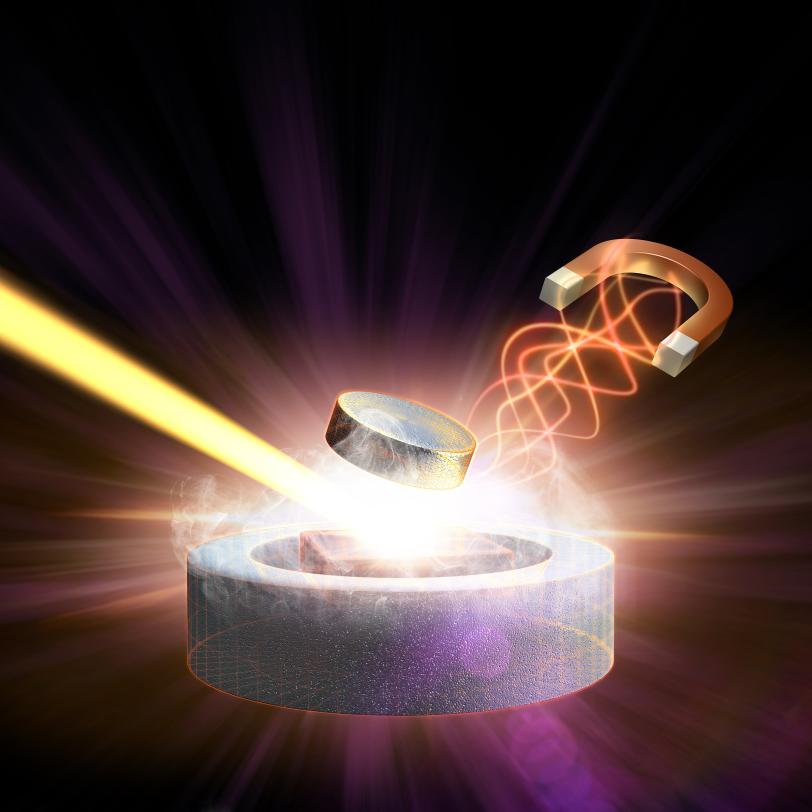

Light-triggered chemicals like iron pentacarbonyl and materials like iron selenide are also seeing plenty of time in the limelight. These kinds of movies have promise for futuristic electronics, computer memory, industrial processes and solar energy harvesting. By revealing the behavior of electrons in various states of conductivity, they could lay the foundation for a new generation of energy technology.

Like in real films, much of the magic happens after the cameras stop rolling.

The world is quite noisy on atomic scales, so sorting good data from bad is a painstaking process. The images have to be analyzed and organized for similar timings, angles and positions and averaged out to give the truest reconstruction possible. All of this is done with home-cooked software that is a continual work in progress.

Advanced algorithms and top-of-the-line supercomputers are needed to deal with the huge amounts of nuanced information in molecular snapshots. Indeed, some of the biggest advances in molecular movies have come from new data analysis techniques. Even then, it may take years after the last frames are captured before the final product is released.

The molecular movie post-production experts’ lives aren’t about to get any easier. A major upgrade to LCLS, known as LCLS-II, will create 10,000 times more frames per second, choking the data pipelines and requiring new techniques for sorting data on the fly, in ways and at speeds that aren’t possible yet.

LCLS-II has the potential to be the best molecular camera ever built, and another step toward fully realistic movies that answer the most elusive questions in science. Armed with documentary evidence, scientists will better understand the natural mechanics that underpin the universe and build upon that knowledge to improve our lives.

LCLS-II: The Next Leap for X-ray Science

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

Molecular movies made at SLAC

The series of images that follow represent a selection of molecular movies made at SLAC and conceptually animated by SLAC graphic artist Greg Stewart over the past several years.

Synchronized molecules

UED Bond Breaking

Perovskites

Thymine

UED iodine

A protein from photosynthetic bacteria

A promising material

feco5_artwork_final_highres.jpg

superconductor-3D-charge-density-wave-SLAC-LCLS.jpg

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.