Tightening the focus of subcellular snapshots

SLAC researchers develop an approach to better guide the preparation of cell slices for cryogenic electron tomography imaging.

By Chris Patrick

Key takeaways

- Cryogenic-electron tomography (cryoET) is a powerful method to reconstruct the internal architecture of a cell in 3D with near-atomic resolution.

- Now, SLAC scientists have developed an approach to better guide the preparation of cell slices for cryoET imaging.

- The new method allows researchers to more accurately target small, rare structures within cells, including invading viruses.

It’s tricky business taking images of tiny structures within cells. One technique, cryogenic electron tomography (cryoET), shoots electrons through a frozen sample. The images formed by the electrons that emerge allow researchers to reconstruct the internal architecture of a cell in 3D with near-atomic resolution.

The thing is, this method doesn’t work if a sample is too thick. Electrons can’t penetrate through most cells, including human cells. Instead, researchers use a beam of ions to mill these beefier cells down to 200 nanometer-thick slices, but then another challenge arises: ensuring the structure of interest – a ribosome or chloroplast, say – is actually contained in this thin slice. It often takes multiple tries to capture the target object in an eroded sample.

Now, by combining light microscopy with ion beam milling, researchers at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory identified an additional signal in fluorescent light that can guide the milling process. This technique improves the accuracy of optically guided milling by roughly an order of magnitude, which will allow cryoET to more easily target small, rare structures within cells, including invading viruses.

“Our approach tells you where your object is inside that final thin cell section very accurately and with a high success rate,” said Peter Dahlberg, an assistant professor at SLAC and Stanford University. “This improvement also greatly enhances efficiency, as you spend less time milling and missing your targets.” Dahlberg developed this time-saving technique, which was published in Nature Communications, with his research associates Anthony Sica and Magda Zaoralová.

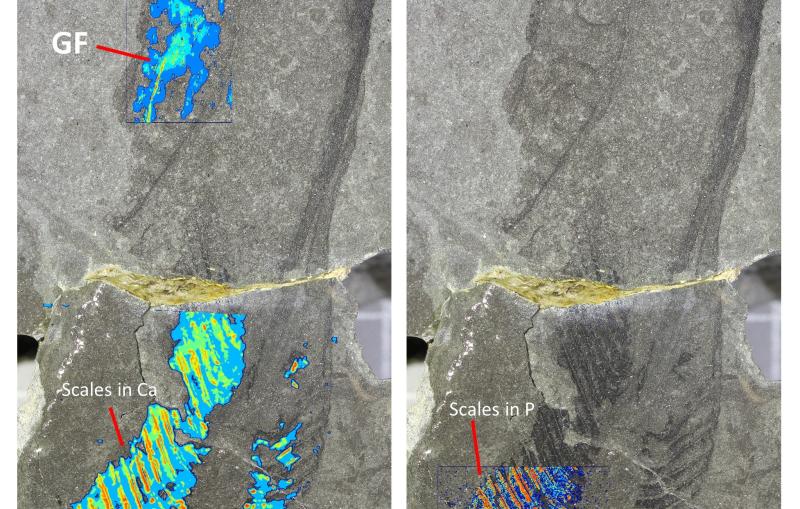

The team used what’s called a tri-coincident system, which aligns the focal planes of three different instruments: a scanning electron microscope, an ion beam for cell milling and an optical microscope for observing tiny objects tagged with fluorescent chemicals. Unlike commercial systems, which do not have co-aligned instruments, this system allows researchers to monitor fluorescence while milling.

Although, tri-coincident systems can’t normally resolve objects smaller than 200 nanometers due to fundamental optical limitations of these instruments, Dahlberg and his team turned to interference, a phenomenon of light wave interactions, to overcome this limitation.

As an ion beam erodes the top of a cell, fluorescent light from the object of interest shines up from underneath. The sample’s top surface reflects these light waves, which then turn around to interfere with the incoming light – much like ripples on a pond that cross and create more complex patterns. In this case, as the surface of the sample is eroded, interference causes the fluorescent light from tagged objects to dim and brighten. Sica wrote software that can precisely locate the fluorescent object based on these patterns of dimming and brightening, allowing more accurate milling.

CryoET of viral cells inside a human cell

To test out the approach, the team imaged a 26 nanometer-wide virus infecting a human cell, demonstrating that this approach can target biological structures previously off limits with cryoET. The technique could be applied to other viral particles and tiny, transient structures involved in cell division, as well as other objects.

“I want to show the field that using this effect and this tri-coincident geometry is the right way to target something very small in cells in their native state,” Dahlberg said.

Assistant Professor, SLAC/StanfordOur approach tells you where your object is inside that final thin cell section very accurately and with a high success rate.

Next, the team wants to incorporate advanced light microscopy methods into the tri-coincident system to further improve the optical image quality and take the most informative cryoET images possible.

“There's a lot of research and development on the milling, but I want to incorporate fancier, sophisticated fluorescence techniques,” Sica said.

The research was funded in part by the DOE Office of Science, the National Institutes of Health and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative DAF, an advised fund of the Silicon Valley Community Foundation.

Citation: A. V. Sica, Nature Communications, 14 January 2026 (s41467-025-65548-8)

For questions or comments, contact SLAC Strategic Communications & External Affairs at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.