SLAC, Stanford researchers discover large protein-free RNA structures

Cryogenic electron microscopy showed for the first time that large RNA complexes can assemble without the help of proteins, expanding our understanding of RNA folding and function.

By Chris Patrick

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) molecules may be best known for their job ferrying the genetic information encoded in DNA to a cell’s protein factories, but these molecules aren’t just a middleman for protein production. In fact, some RNA molecules don’t code for proteins at all and serve various other important functions in cells, such as regulating gene expression and catalyzing chemical reactions. However, the functions of many non-coding RNAs remain mysterious.

Now, searching for hints about the roles of a trio of non-coding RNA molecules produced en masse in bacterial cells, researchers from Stanford University, the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, and the National Institutes of Health stumbled upon unexpectedly extravagant, multistrand complexes made entirely of RNA, which the team reported today in the journal Nature.

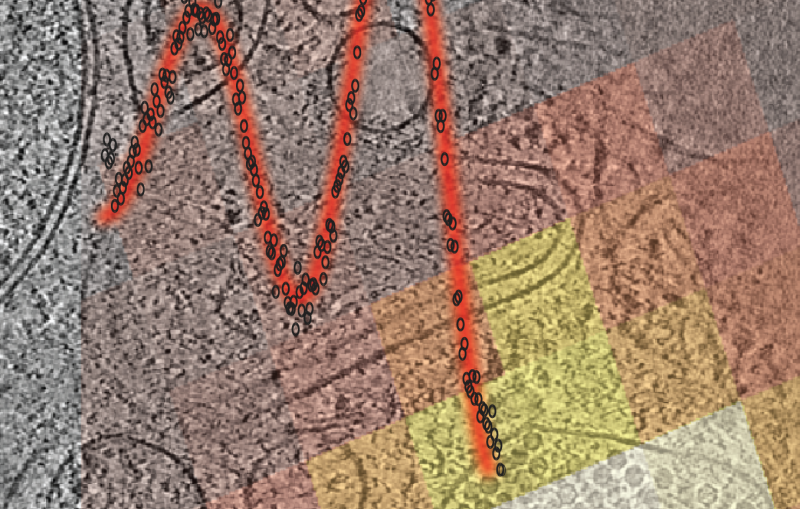

“We discovered that these RNAs fold into beautiful symmetric complexes without any proteins or other molecules to support them. This is something we haven't seen before in nature,” said Stanford graduate student and lead author Rachael Kretsch.

The discovery expands our current understanding of how RNA assembles into large, complex structures, and it could even inspire the design of similar structures for biomedical or biotechnological purposes, the researchers said.

Professor of Biochemistry at Stanford University School of Medicine.No one had any idea previously what these ornate RNA molecules were doing.

CryoEM reveals unexpected structures

One way researchers figure out the function of a non-coding RNA is by getting rid of it in a cell. The way the cell subsequently dies can provide information on the RNA’s function. But this approach doesn’t work for the three particular RNAs studied here because cells can survive without them.

Hoping to gain more insights into their biological functions, the research team decided to analyze the 3D structures of the RNA molecules. They took their samples to SLAC, where they used cryogenic electron microscopy (cryoEM) to produce detailed images of the molecules.

For each RNA, the team expected the images to show one strand of the molecule to be folded into a compact structure. Instead, they saw unfamiliar large complexes made up of multiple strands of the same RNA – structures they didn’t know were possible without the support of proteins.

Cryo-EM at SLAC

Cryo-EM allows scientists to make detailed 3D images of DNA, RNA, proteins, viruses, cells and the tiny molecular machines within the cell, revealing how they change shape and interact in complex ways while carrying out life’s functions.

Two of the RNAs assembled into cage-shaped structures made up of eight and 14 strands, respectively – shapes that suggest these RNA complexes could potentially carry something inside of them. In the third RNA molecule, two strands “kiss” to form a diamond-shaped scaffold that could potentially work as a sensor, where the kiss is formed under certain conditions and broken under others.

“There are relatively few RNA-only assembly structures compared to protein assembly structures in the Protein Data Bank. These studies further demonstrate the power of cryoEM for molecular structure determination of these under-studied macromolecules, forming the basis for the search of their biological functions,” said co-principal investigator Wah Chiu, professor at SLAC and Stanford and director of the CryoEM and Bioimaging division of SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL).

From structure to function to design

Next, the researchers want to figure out if the RNA structures actually interact with other molecules inside the cell to learn more about their potential biological functions.

“No one had any idea previously what these ornate RNA molecules were doing. These unexpected structures suggest that the RNA might be cages or sensors and are inspiring new biological experiments and applications in medicine,” said co-principal investigator Rhiju Das, professor of biochemistry at Stanford University School of Medicine.

In addition to deepening our understanding of the roles RNAs play in biology, the study also provided new insights into the 3D structures a given RNA sequence can fold into. Being able to predict such structures could aid in the design of RNA molecules for various applications, such as drug delivery and medical imaging, but researchers currently lack that reliable predictive power.

“I think this work is a wealth of data for improving our ability to predict how an RNA is going to fold, as well as enabling us to actually design an RNA of a given fold,” Kretsch said.

This work was funded by Stanford Bio-X, the National Institute of Health, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the National Science Foundation, and the G. Harold & Leila Y. Mathers Foundation. CryoEM experiments were done at the Stanford-SLAC CryoEM Center at SLAC. SSRL is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

Citation: Rachael Kretsch et al., Nature, 6 May 2025 (10.1038/s41586-025-09073-0)

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.