Exploring Heat and Energy at the Smallest Scales

In a recent experiment at SLAC's Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, scientists "tickled" atoms to explore the flow of heat and energy across materials at ultrasmall scales.

By Glenn Roberts Jr.

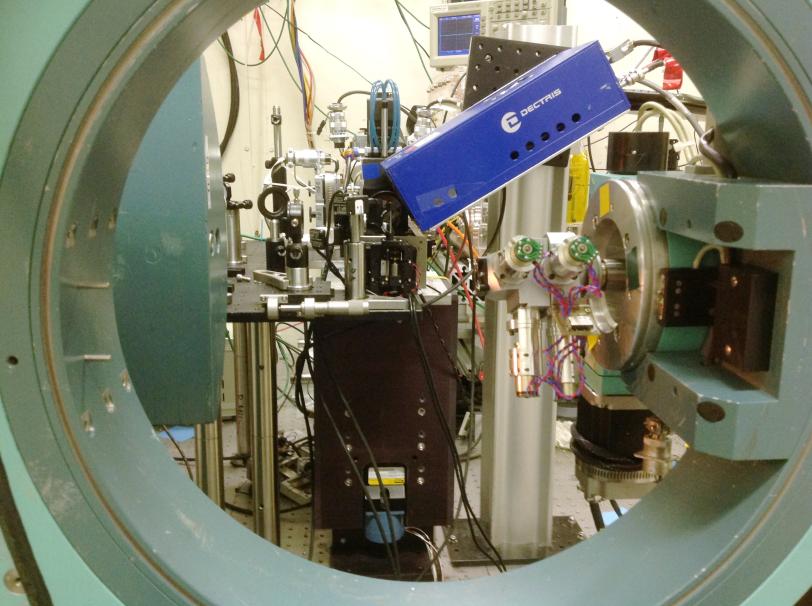

In a recent experiment at SLAC's Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), scientists "tickled" atoms to explore the flow of heat and energy across materials at ultrasmall scales. The experiment, detailed in the May 6 edition of Structural Dynamics, enabled them to see subtle light-driven changes in the atomic structure of thin materials, relevant to thermoelectric and electronic devices.

"These results show that we can really follow the flow of energy across nanoscale devices, and resolve the dynamics in a way that hasn't been possible before. It opens the door to new, more efficient types of devices," said research team member Aaron Lindenberg, an assistant professor at SLAC and Stanford affiliated with the Stanford PULSE Institute and the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences.

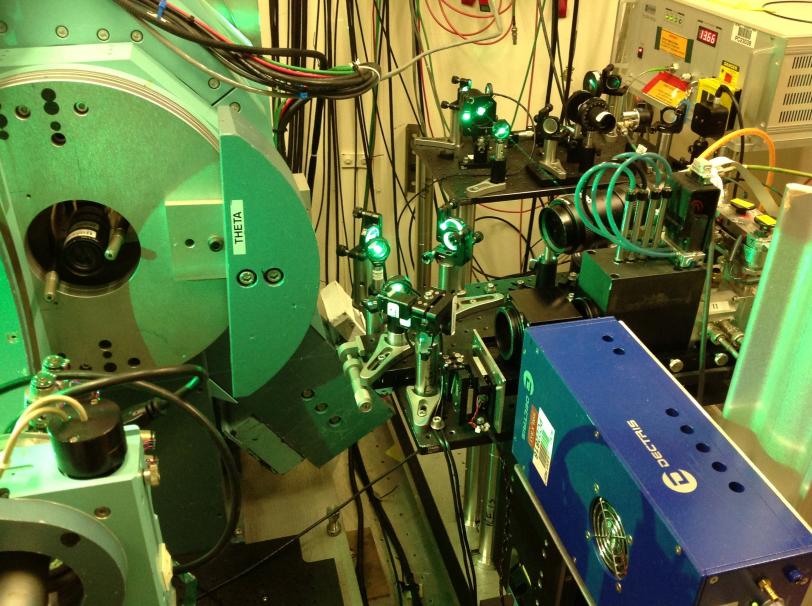

Striking superthin materials with specially timed X-ray and laser pulses fired at a rate of more than one million times per second, scientists caused atoms to vibrate and measured their movement with accuracy down to a fraction of a femtometer, which is a million-billionth of a meter.

"We were able to see remarkably small structural changes that we had never envisioned we could," said Michael Kozina, a graduate student with the Stanford PULSE Institute, a joint institute of SLAC and Stanford, who led the research.

Researchers observed a longer-than-expected time delay, measured at about a billionth of a second, in the transfer of heat from the thin films to the surface below.

The cause of this delay has important implications for materials research, Kozina said. "In electronic devices, you want to dissipate the heat as fast as you can, and in thermoelectric devices you want to maintain that delay as long as you can and prevent heat from flowing rapidly," he added. "Now we have a way to directly look at this."

The response of the materials to the rapid-fire laser pulses, which was too fast to be measured for each individual pulse, was averaged out over time.

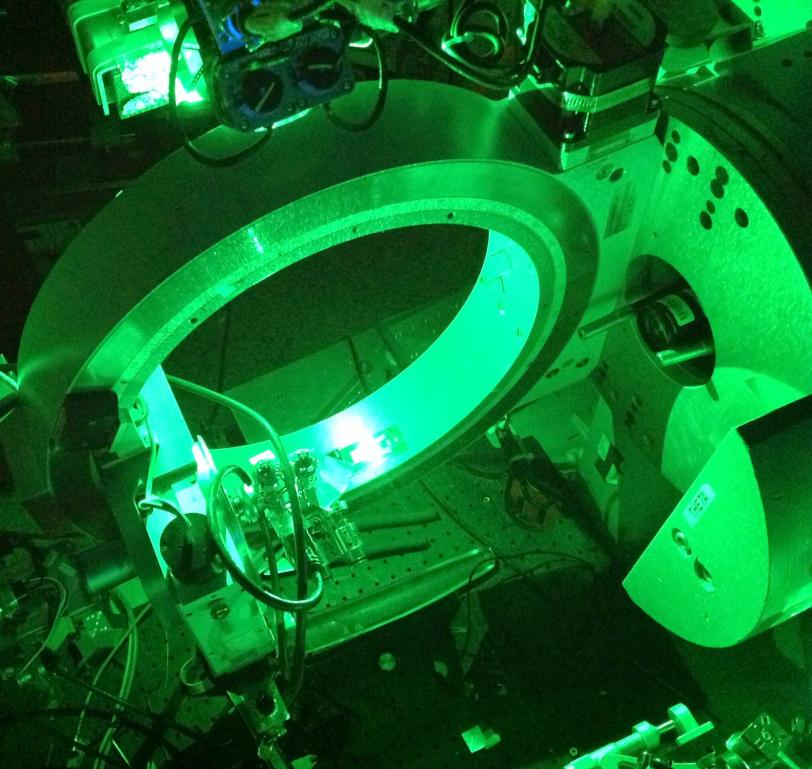

The experiment was performed during a series of special operating periods at SSRL known as "low-alpha mode," in which the accelerator ring that feeds X-rays to SSRL experiments is tuned to produce shorter-than-usual pulses, measured in trillionths of a second, and its electric current is dialed down. SSRL is one of just a few synchrotrons in the world to run in low-alpha mode.

“Short-pulse research is an important component in SSRL’s science strategy and provides capabilities that are complementary to the Linac Coherent Light Source,” SLAC's X-ray laser, said Piero Pianetta, acting director of SSRL.

Kozina said low-alpha-mode experiments are complementary to other research the group has conducted at LCLS and using other tools, because they allow researchers to probe very slight processes in materials and don't require jarring the material with higher-energy pulses to get a measurable response. "It's like the difference between tickling the atomic structure in the samples versus hitting it with a hammer," he said.

The findings from this experiment, which explored films of bismuth, bismuth ferrite and PZT (a blend containing lead, zirconium and titanium) measuring just billionths of an inch thick, mark the first journal-published scientific results obtained during low-alpha-mode operations at SSRL.

A next step in the research is to study different alignments of the samples with respect to the surface they rest on to measure whether those changes slow or speed the transfer of heat and charge, Kozina said.

SSRL has three scheduled periods each year, each spanning a few days, for low-alpha mode, and Kozina said that the latest research is the culmination of a handful of experimental runs over the course of several years. "Incremental successes have finally reached the threshold of experimental success," he said, "The goal is to make this operating mode more turn-key and open it up to visiting researchers."

Citation: M. Kozina, T. Hu, et al., Structural Dynamics, 6 May 2014 (10.1063/1.4875347)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, California, SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science.

SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource is a third-generation light source producing extremely bright X-rays for basic and applied science. A DOE national user facility, SSRL attracts and supports scientists from around the world who use its state-of-the-art capabilities to make discoveries that benefit society. For more information visit http://www-ssrl.slac.stanford.edu.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.