Scientists Discover Potential Way to Make Graphene Superconducting

Scientists have discovered a potential way to make graphene – a single layer of carbon atoms with great promise for future electronics – superconducting, a state in which it would carry electricity with 100 percent efficiency.

Menlo Park, Calif. — Scientists at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University have discovered a potential way to make graphene – a single layer of carbon atoms with great promise for future electronics – superconducting, a state in which it would carry electricity with 100 percent efficiency.

Researchers used a beam of intense ultraviolet light to look deep into the electronic structure of a material made of alternating layers of graphene and calcium. While it's been known for nearly a decade that this combined material is superconducting, the new study offers the first compelling evidence that the graphene layers are instrumental in this process, a discovery that could transform the engineering of materials for nanoscale electronic devices.

“Our work points to a pathway to make graphene superconducting – something the scientific community has dreamed about for a long time, but failed to achieve,” said Shuolong Yang, a graduate student at the Stanford Institute of Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES) who led the research at SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL).

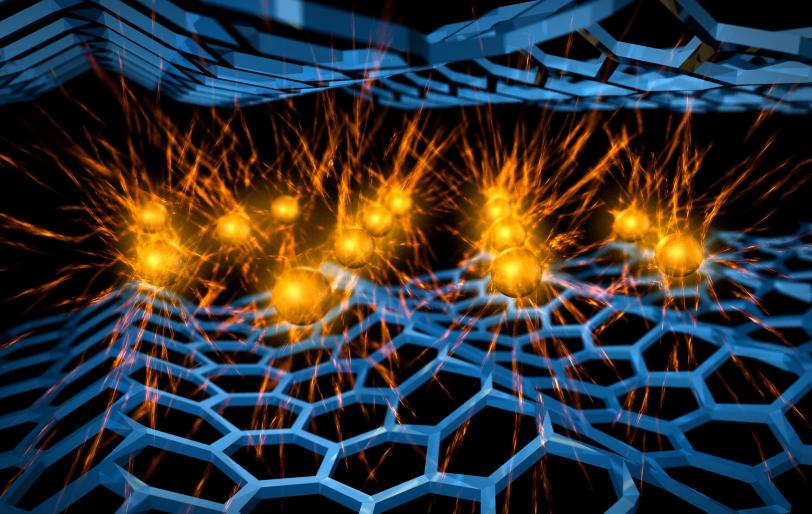

The researchers saw how electrons scatter back and forth between graphene and calcium, interact with natural vibrations in the material’s atomic structure and pair up to conduct electricity without resistance. They reported their findings March 20 in Nature Communications.

Graphite Meets Calcium

Graphene, a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a honeycomb pattern, is the thinnest and strongest known material and a great conductor of electricity, among other remarkable properties. Scientists hope to eventually use it to make very fast transistors, sensors and even transparent electrodes.

The classic way to make graphene is by peeling atomically thin sheets from a block of graphite, a form of pure carbon that’s familiar as the lead in pencils. But scientists can also isolate these carbon sheets by chemically interweaving graphite with crystals of pure calcium. The result, known as calcium intercalated graphite or CaC6, consists of alternating one-atom-thick layers of graphene and calcium.

The discovery that CaC6 is superconducting set off a wave of excitement: Did this mean graphene could add superconductivity to its list of accomplishments? But in nearly a decade of trying, researchers were unable to tell whether CaC6’s superconductivity came from the calcium layer, the graphene layer or both.

Observing Superconducting Electrons

For this study, samples of CaC6 were made at University College London and brought to SSRL for analysis.

“These are extremely difficult experiments,” said Patrick Kirchmann, a staff scientist at SLAC and SIMES. But the purity of the sample combined with the high quality of the ultraviolet light beam allowed them to see deep into the material and distinguish what the electrons in each layer were doing, he said, revealing details of their behavior that had not been seen before.

“With this technique, we can show for the first time how the electrons living on the graphene planes actually superconduct,” said SIMES graduate student Jonathan Sobota, who carried out the experiments with Yang. “The calcium layer also makes crucial contributions. Finally we think we understand the superconducting mechanism in this material.”

Although applications of superconducting graphene are speculative and far in the future, the scientists said, they could include ultra-high frequency analog transistors, nanoscale sensors and electromechanical devices and quantum computing devices.

The research team was supervised by Zhi-Xun Shen, a professor at SLAC and Stanford and SLAC’s advisor for science and technology, and included other researchers from SLAC, Stanford, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and University College London. The work was supported by the DOE’s Office of Science, the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council of UK and the Stanford Graduate Fellowship program.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

The Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES) is a joint institute of SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University. SIMES studies the nature, properties and synthesis of complex and novel materials in the effort to create clean, renewable energy technologies. For more information, visit simes.slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) is a third-generation light source producing extremely bright X-rays for basic and applied science. A DOE national user facility, SSRL attracts and supports scientists from around the world who use its state-of-the-art capabilities to make discoveries that benefit society. For more information, visit ssrl.slac.stanford.edu.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit science.energy.gov.

Citation: S. L. Yang et al., Nature Communications, 20 March 2014 (10.1038/ncomms4493)

Press Office Contact:

Andy Freeberg, afreeberg@slac.stanford.edu, (650) 926-4359

Scientist Contact:

Shuolong Yang, syang2@stanford.edu, (650) 725-0440