All Systems Go: A New High-energy Record for LCLS

John Hill watched with eager anticipation as controllers ramped up the power systems driving SLAC's X-ray laser in an attempt to achieve the record high energies needed to make his experiment a runaway success.

By Glenn Roberts Jr.

John Hill watched with eager anticipation as controllers ramped up the power systems driving SLAC's X-ray laser in an attempt to achieve the record high energies needed to make his experiment a runaway success.

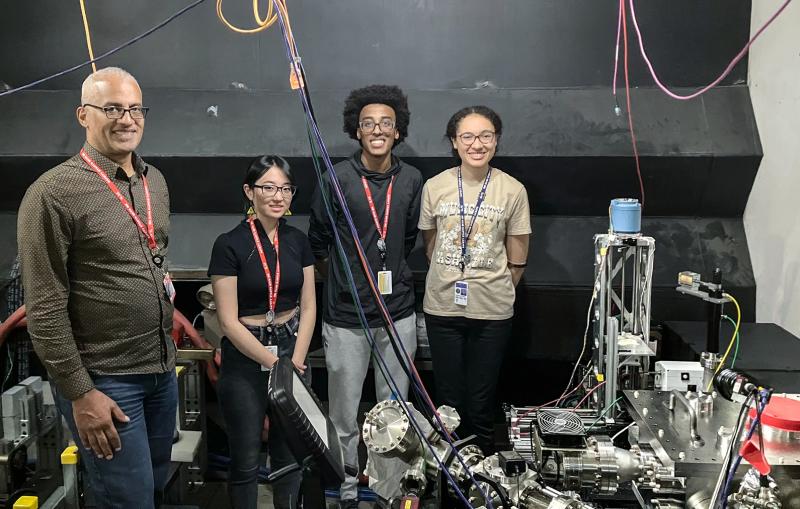

The Brookhaven National Laboratory scientist was the leader of a research team that had come from Illinois, Germany, Switzerland and England to use the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), and this was their last day. They would get only one shot.

Gathered in SLAC's Main Control Center with LCLS staff members, the team watched as blips of green appeared in a long sequence across a screen. Each represented a klystron working at full power to accelerate a beam of electrons, which would be converted to LCLS X-ray pulses. To reach the high X-ray energies they were aiming for, all of the 80 klystrons associated with LCLS would need to operate at near-peak levels.

In a few instances, the lights turned red. "The users asked, 'Is it over?'" recalled LCLS staff scientist Marcin Sikorski. "No. They brought the klystrons back quickly, in a matter of minutes."

With all systems go, the energy of the X-ray pulses soared to 11.2 kilo-electronvolts (keV) – a new record, about 35 percent higher than LCLS had originally been designed to reach – and stayed there for 24 hours nearly uninterrupted. It's a performance the LCLS staff hopes to duplicate and even exceed, to the benefit of a wide range of future experiments.

The mood in the control center was electric, Hill said: "They were high-fiving each other. 'Excitement' is definitely the best word. Everything had to be perfect for this to work."

There was tremendous teamwork by electricians and other staff across the Accelerator Directorate, Sikorski said, "with huge doses of luck."

The record-high energy level was key for Hill's experiment, said David Fritz, acting director for the LCLS Science, Research and Development Division, as it tapped a powerful resonance – like the loud plucking of a violin string – in iridium, a chemical component of the sample under study.

When strongly enhanced by high-energy X-rays, as it was that day, this resonance "gives you sensitivity to particular electronic states in atoms," Fritz said, which in this sample "happens to be very important for magnetic properties." Without this high energy, the experiment had detected only a faint signal and generated a limited amount of data.

After hitting the energy record, the detector was suddenly measuring an "enormous amount of X-rays" about 150 times more intense than before, Hill said, producing a very clear and distinct signal.

"What had been a few dots on the detector became a bright cluster of intensity," Hill said. "We got 24 hours of data in this wonderful condition." After the successful test, Hill is already talking about plans for follow-up experiments at LCLS, including experiments that add other laser pulses to study how processes evolve over time.

Axel Brachmann, LCLS Accelerator Systems Division director, said the accelerator was performing so optimally during the experiment that the staff pushed the machine to an even higher energy after it had concluded.

"We explored how far we could go. We ran up to 11.9 keV," he said, adding that the energy might even be notched a bit higher in a future testing mode: "With more tuning we could probably bring it up."

The accelerator staff had pushed the other end of the LCLS energy range just last year, successfully dialing back the minimum energy of LCLS X-ray pulses to about one-third the minimum energy it was originally designed to run at, which opened up a new realm of possible experiments.

Hill said he was impressed with all the work that went into boosting the results of his team's experiment.

"Pulling this out of their hat on the last day, it was fantastic," he said.

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.