Data-mining for Crystal 'Gold' at SLAC's X-ray Laser

A new tool for analyzing mountains of data from SLAC’s Linac Coherent Lightsource (LCLS) X-ray laser can produce high-quality images of important proteins using fewer samples. Scientists hope to use it to reveal the structures and functions of proteins that have proven elusive, as well as mine data from past experiments for new information

By Glenn Roberts Jr.

A new tool for analyzing mountains of data from SLAC’s Linac Coherent Lightsource (LCLS) X-ray laser can produce high-quality images of important proteins using fewer samples. Scientists hope to use it to reveal the structures and functions of proteins that have proven elusive, as well as mine data from past experiments for new information.

"Such analytical tools might be as important to LCLS experiments as better detectors, sample-delivery systems and other instruments," said Uwe Bergmann, director of LCLS and a member of a research collaboration that has tested the software. "Continued improvements in methods like this will be critical for very precious samples – particularly when time or the amount of sample is limited.”

The software package, known as the Computational Crystallography Toolbox for X-ray Free-electron Lasers or cctbx.xfel, was developed as a part of an international project to study proteins involved in oxygen production in photosynthesis, but can be applied to other protein studies as well. It should be especially helpful in analyzing proteins that are difficult to crystallize in large quantities for experiments, including many relevant to fighting disease. The software toolbox is freely available online, and users can get help online or via email.

Detailed in a paper published in the March 16 edition of Nature Methods, the new tool is designed to glean more information from protein samples based on a customized, improved analysis of LCLS X-ray images.

The software finds new ways to precisely match LCLS data with Bragg's Law, the 101-year-old discovery that describes the mathematics of how X-rays project the molecular blueprints of tiny crystallized samples onto a detector. It does so by factoring in painstaking measurements of the surfaces of LCLS X-ray detectors.

"We're trying to really accurately measure the geometry of the detectors – to know where the measurements are being made to the level of microns," said Nicholas Sauter, a computer staff scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory who led the software development effort with Berkeley Lab senior scientist Paul Adams. This detailed mapping of the detectors provides a more accurate analysis of LCLS X-ray images.

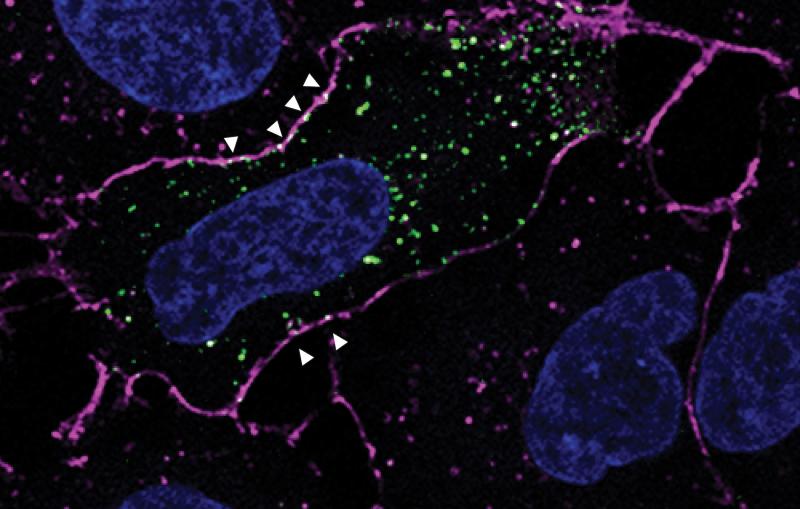

The software also analyzes spots in the X-ray images that other tools reject or overlook, such as streaked, curved, dim or fuzzy features, increasing the number of usable images. “In addition, it is designed to resolve sharper details of the atomic structure,” Sauter said.

The developers adapted the software from LABELIT, a tool Sauter released a decade ago to analyze data from synchrotrons, the most widely used X-ray facilities for studying crystallized biological samples.

X-ray free-electron lasers such as LCLS, with ultrashort X-ray pulses that are millions of times brighter than synchrotron X-rays, are proving a powerful new force in solving molecular mysteries that synchrotrons cannot, but they bring a new set of scientific challenges.

At synchrotrons, scientists typically study frozen crystals one at a time, rotating each one slowly and taking multiple X-ray images.

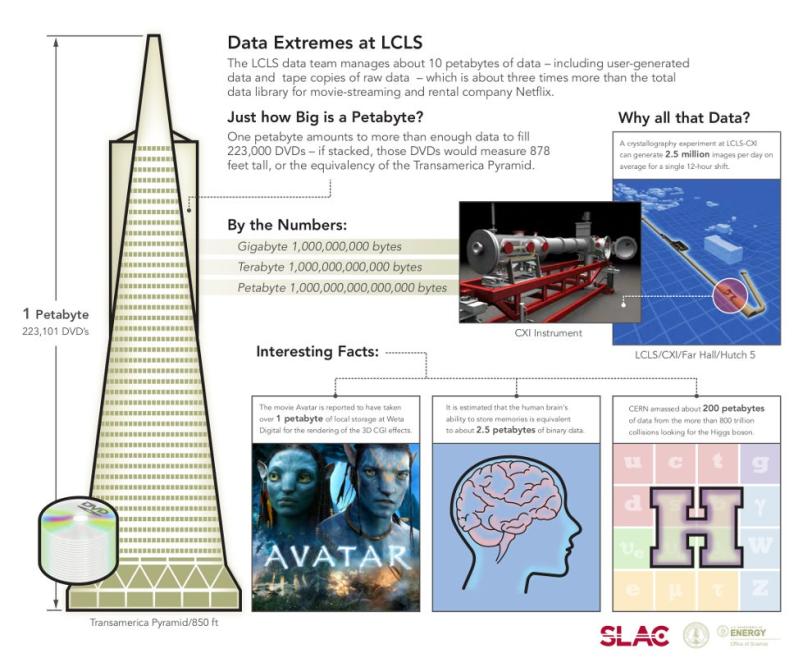

LCLS can study smaller crystals and under more natural conditions, but it requires a much larger number of crystals, which are typically suspended in a liquid or gel and jetted into the path of the X-rays. Because the crystals are tumbling randomly when the X-ray snapshots are taken and only one image can be taken of each crystal, scientists must gather tens of thousands of high-quality images to get a complete picture of a protein structure. A recent experiment at LCLS collected enough data to fill about 2,335 standard Blu-ray video discs, Sauter said.

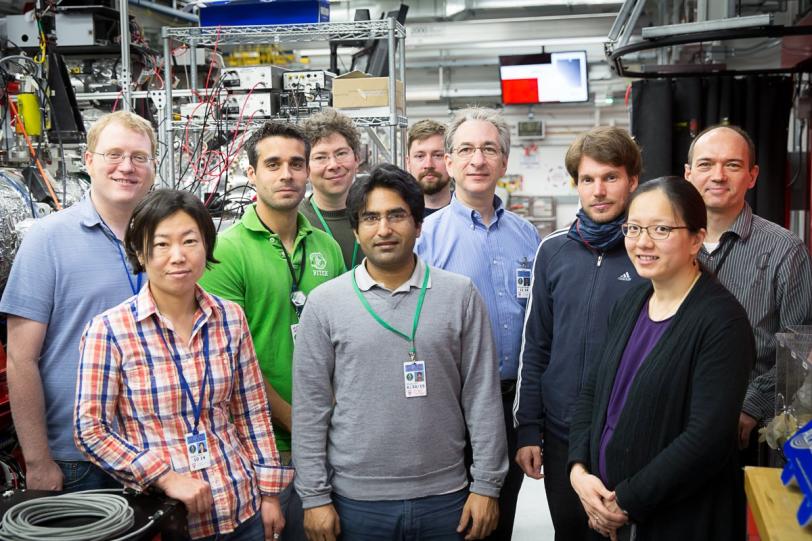

Junko Yano, a staff scientist at Berkeley Lab whose research team includes Berkeley Lab senior scientist Vittal Yachandra, has used the new data-analysis tool to study the molecular machinery at work in photosynthesis. She said even in cases where it is easy to produce crystals and generate a lot of data, the software could improve the resolution of protein structures by capturing more details from the highest-quality crystals.

"With many biological systems we may not have this luxury of easily producing a lot of crystals,” she added, “so this will help us to minimize the amount of samples we need to collect high-quality data, both at LCLS and at other free-electron X-ray laser facilities that are coming on line.”

Researchers at SLAC, Humboldt University in Germany, Umeå University in Sweden and the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in France also participated on the research team that tested the software.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, California, SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. To learn more, please visit www.slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC’s LCLS is the world’s most powerful X-ray free-electron laser. A DOE Office of Science national user facility, its highly focused beam shines a billion times brighter than previous X-ray sources to shed light on fundamental processes of chemistry, materials and energy science, technology and life itself. For more information, visit lcls.slac.stanford.edu.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Citation

Johan Hattne, Nathaniel Echols et al., Nature Methods, 16 March 2014 (10.1038/nmeth.2887)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.