Experiments shed light on pressure-driven ionization in giant planets and stars

The results offer important implications for astrophysics and nuclear fusion research.

Scientists have conducted laboratory experiments at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) that provide new insights on the complex process of pressure-driven ionization in giant planets and stars. Their research, published today in Nature, unveils the material properties and behavior of matter under extreme compression, offering important implications for astrophysics and nuclear fusion research.

“If you can recreate conditions that occur in a stellar object, then you can actually find out what's going on inside of it,” said collaborator Siegfried Glenzer, director of the High Energy Density Division at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. “It’s like putting a thermometer into the star and measuring how hot it is and what these conditions do to the atoms inside the material. It can teach us new ways to manipulate matter for fusion energy sources.”

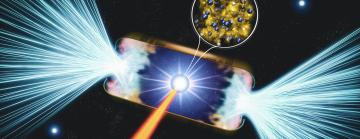

The international research team used the world's largest and most energetic laser, the National Ignition Facility (NIF), to generate the extreme conditions necessary for pressure-driven ionization. By employing 184 laser beams, the team heated the inside of a cavity, converting the laser energy into X-rays that heated a 2 mm diameter beryllium shell placed in the center. As the outside of the shell rapidly expanded due to the heating, the inside accelerated inwards reaching temperatures around two million kelvins and pressures up to three billion atmospheres, creating a tiny piece of matter, as found in dwarf stars, for a few nanoseconds in the laboratory.

The highly compressed beryllium sample, up to 30 times its ambient solid density, was probed with X-rays to figure out its density, temperature, and electron structure. The findings revealed that, following strong heating and compression, at least three out of four electrons in beryllium transitioned into conducting states. Additionally, the study uncovered unexpectedly weak elastic scattering, indicating reduced localization, or freeing up, of the remaining electron.

Matter in the interior of giant planets and some relatively cool stars is highly compressed by the weight of the layers above. At such high pressures, generated by high compression, the proximity of atomic nuclei leads to interactions between electronic bound states of neighboring ions and ultimately to their complete ionization. While ionization in burning stars is primarily determined by temperature, pressure-driven ionization dominates in cooler objects.

Despite its importance for the structure and evolution of celestial objects, pressure ionization as a pathway to highly ionized matter is not well understood theoretically. Moreover, the extreme states of matter required are very difficult to create and study in the laboratory, said LLNL physicist Tilo Döppner, who led the project.

“By recreating extreme conditions similar to those inside giant planets and stars, we were able to observe changes in material properties and electron structure that are not captured by current models,” Döppner said. “Our work opens new avenues for studying and modeling the behavior of matter under extreme compression. The ionization in dense plasmas is a key parameter as it affects the equation of state, thermodynamic properties, and radiation transport through opacity.”

The research also has significant implications for inertial confinement fusion experiments at NIF, where X-ray absorption and compressibility are key parameters for optimizing high performance fusion experiments. A comprehensive understanding of pressure- and temperature-driven ionization is essential for modeling compressed materials and ultimately for developing an abundant, carbon-free energy source by means of laser-driven nuclear fusion, Döppner said.

“The unique capabilities at the National Ignition Facility are unrivaled. There is only one place on Earth where we can create the extreme compressions of planetary cores and stellar interiors in the laboratory, and study and observe them, and that’s on the world’s largest and most energetic laser,” said Bruce Remington, NIF Discovery Science program leader. “Building on the foundation of previous research at NIF, this work is expanding the frontiers of laboratory astrophysics.”

The team included scientists from University of Rostock (Germany), University of Warwick (U.K.), GSI Helmholtz Center for Heavy Ion Research (Germany), University of California Berkeley, Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (Germany), University of Lyon (France), Los Alamos National Laboratory, the Atomic Weapons Establishment (U.K.), Imperial College London (U.K.), and First Light Fusion Ltd. (U.K.).

This article has been adapted from a press release written by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

Citation: T. Döppner et al., Nature, 24 May 2023 (10.1038/s41586-023-05996-8)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.