How a soil microbe could rev up artificial photosynthesis

Researchers discover that a spot of molecular glue and a timely twist help a bacterial enzyme convert carbon dioxide into carbon compounds 20 times faster than plant enzymes do during photosynthesis. The results stand to accelerate progress toward converting carbon dioxide into a variety of products.

By Glennda Chui

Plants rely on a process called carbon fixation – turning carbon dioxide from the air into carbon-rich biomolecules – for their very existence. That’s the whole point of photosynthesis, and a cornerstone of the vast interlocking system that cycles carbon through plants, animals, microbes and the atmosphere to sustain life on Earth.

But the carbon fixing champs are not plants, but soil bacteria. Some bacterial enzymes carry out a key step in carbon fixation 20 times faster than plant enzymes do, and figuring out how they do this could help scientists develop forms of artificial photosynthesis to convert the greenhouse gas into fuels, fertilizers, antibiotics and other products.

Now a team of researchers from the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Stanford University, Max Planck Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology in Germany, DOE’s Joint Genome Institute (JGI) and the University of Concepción in Chile has discovered how a bacterial enzyme – a molecular machine that facilitates chemical reactions – revs up to perform this feat.

Rather than grabbing carbon dioxide molecules and attaching them to biomolecules one at a time, they found, this enzyme consists of pairs of molecules that work in sync, like the hands of a juggler who simultaneously tosses and catches balls, to get the job done faster. One member of each enzyme pair opens wide to catch a set of reaction ingredients while the other closes over its captured ingredients and carries out the carbon-fixing reaction; then, they switch roles in a continual cycle.

A single spot of molecular “glue” holds each pair of enzymatic hands together so they can alternate opening and closing in a coordinated way, the team discovered, while a twisting motion helps hustle ingredients and finished products in and out of the pockets where the reactions take place. When both glue and twist are present, the carbon-fixing reaction goes 100 times faster than without them.

“This bacterial enzyme is the most efficient carbon fixer that we know of, and we came up with a neat explanation of what it can do,” said Soichi Wakatsuki, a professor at SLAC and Stanford and one of the senior leaders of the study, which was published in ACS Central Science this week.

“Some of the enzymes in this family act slowly but in a very specific way to produce just one product,” he said. “Others are much faster and can craft chemical building blocks for all sorts of products. Now that we know the mechanism, we can engineer enzymes that combine the best features of both approaches and do a very fast job with all sorts of starting materials."

Improving on nature

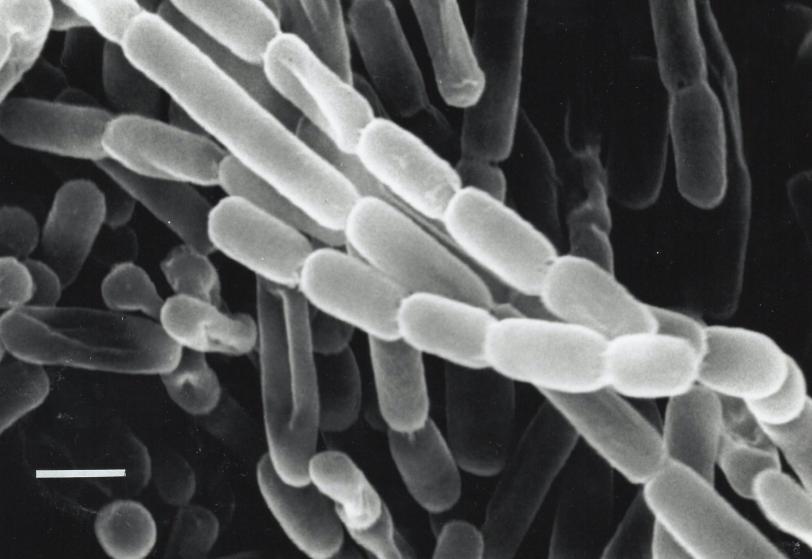

The enzyme the team studied is part of a family called enoyl-CoA carboxylases/reductases, or ECRs. It comes from soil bacteria called Kitasatospora setae, which in addition to their carbon-fixing skills can also produce antibiotics.

Wakatsuki heard about this enzyme family half a dozen years ago from Tobias Erb of the Max Planck Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology in Germany and Yasuo Yoshikuni of JGI. Erb’s research team had been working to develop bioreactors for artificial photosynthesis to convert carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere into all sorts of products.

As important as photosynthesis is to life on Earth, Erb said, it isn’t very efficient. Like all things shaped by evolution over the eons, it’s only as good as it needs to be, the result of slowly building on previous developments but never inventing something entirely new from scratch.

What’s more, he said, the step in natural photosynthesis that fixes CO2 from the air, which relies on an enzyme called Rubisco, is a bottleneck that bogs the whole chain of photosynthetic reactions down. So using speedy ECR enzymes to carry out this step, and engineering them to go even faster, could bring a big boost in efficiency.

“We aren’t trying to make a carbon copy of photosynthesis,” Erb explained. “We want to design a process that’s much more efficient by using our understanding of engineering to rebuild the concepts of nature. This ‘photosynthesis 2.0’ could take place in living or synthetic systems such as artificial chloroplasts – droplets of water suspended in oil.”

Portraits of an enzyme

Wakatsuki and his group had been investigating a related system, nitrogen fixation, which converts nitrogen gas from the atmosphere into compounds that living things need. Intrigued by the question of why ECR enzymes were so fast, he started collaborating with Erb’s group to find answers.

Hasan DeMirci, a research associate in Wakatsuki’s group who is now an assistant professor at Koc University and investigator with the Stanford PULSE Institute, led the effort at SLAC with help from half a dozen SLAC summer interns he supervised. “We train six or seven of them every year, and they were fearless,” he said. “They came with open minds, ready to learn, and they did amazing things.”

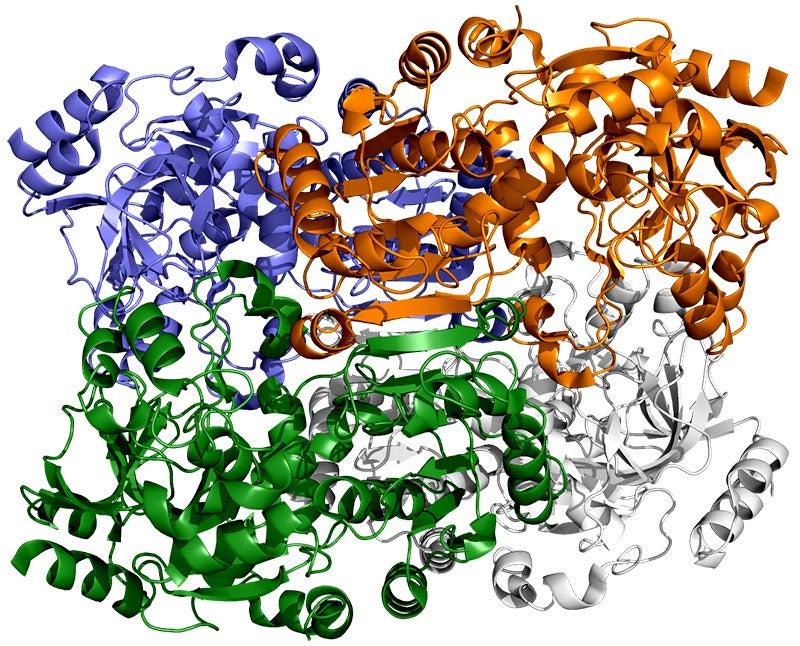

The SLAC team made samples of the ECR enzyme and crystallized them for examination with X-rays at the Advanced Photon Source at DOE’s Argonne National Laboratory. The X-rays revealed the molecular structure of the enzyme – the arrangement of its atomic scaffolding – both on its own and when attached to a small helper molecule that facilitates its work.

Further X-ray studies at SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) showed how the enzyme’s structure shifted when it attached to a substrate, a kind of molecular workbench that assembles ingredients for the carbon fixing reaction and spurs the reaction along.

Finally, a team of researchers from SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) carried out more detailed studies of the enzyme and its substrate at Japan’s SACLA X-ray free-electron laser. The choice of an X-ray laser was important because it allowed them to study the enzyme’s behavior at room temperature – closer to its natural environment – with almost no radiation damage.

Meanwhile, Erb’s group in Germany and Associate Professor Esteban Vöhringer-Martinez’s group at the University of Concepción in Chile carried out detailed biochemical studies and extensive dynamic simulations to make sense of the structural data collected by Wakatsuki and his team.

The simulations revealed that the opening and closing of the enzyme’s two parts don’t just involve molecular glue, but also twisting motions around the central axis of each enzyme pair, Wakatsuki said.

“This twist is almost like a rachet that can push a finished product out or pull a new set of ingredients into the pocket where the reaction takes place,” he said. Together, the twisting and synchronization of the enzyme pairs allow them to fix carbon 100 times a second.

The ECR enzyme family also includes a more versatile branch that can interact with many different kinds of biomolecules to produce a variety of products. But since they aren’t held together by molecular glue, they can’t coordinate their movements and therefore operate much more slowly.

“If we can increase the rate of those sophisticated reactions to make new biomolecules,” Wakatsuki said, “that would be a significant jump in the field.”

From static shots to fluid movies

So far the experiments have produced static snapshots of the enzyme, the reaction ingredients and the final products in various configurations.

“Our dream experiment,” Wakatsuki said, “would be to combine all the ingredients as they flow into the path of the X-ray laser beam so we could watch the reaction take place in real time.”

The team actually tried that at SACLA, he said, but it didn’t work. “The CO2 molecules are really small, and they move so fast that it’s hard to catch the moment when they attach to the substrate,” he said. “Plus the X-ray laser beam is so strong that we couldn’t keep the ingredients in it long enough for the reaction to take place. When we pressed hard to do this, we managed to break the crystals.”

An upcoming high-energy upgrade to LCLS will likely solve that problem, he added, with pulses that arrive much more frequently - a million times per second – and can be individually adjusted to the ideal strength for each sample.

Wakatsuki said his team continues to collaborate with Erb’s group, and it’s working with the LCLS sample delivery group and with researchers at the SLAC-Stanford cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) facilities to find a way to make this approach work.

Researchers from the RIKEN Spring-8 Center and Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute also contributed to this work, which received major funding from the DOE Office of Science. Much of the preliminary work for this study was carried out by SLAC summer intern Yash Rao; interns Brandon Hayes, E. Han Dao and Manat Kaur also made key contributions. DOE’s Joint Genome Institute provided the DNA used to produce the ECR samples. SSRL, LCLS, the Advanced Photon Source and the Joint Genome Institute are all DOE Office of Science user facilities.

Citation: Hasan DeMirci et al., ACS Central Science, 25 April 2022 (10.1021/acscentsci.2c00057)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.