SLAC and Stanford researchers reveal the fourth signature of the superconducting transition in cuprates

The results cap 15 years of detective work aimed at understanding how these materials transition into a superconducting state where they can conduct electricity with no loss.

By Glennda Chui

When an exciting and unconventional new class of superconducting materials was discovered 35 years ago, researchers cheered.

Like other superconductors, these materials, known as copper oxides or cuprates, conducted electricity with no resistance or loss when chilled below a certain point – but at much higher temperatures than scientists had thought possible. This raised hopes of getting them to work at close to room temperature for perfectly efficient power lines and other uses.

Research quickly confirmed that they showed two more classic traits of the transition to a superconducting state: As superconductivity developed, the material expelled magnetic fields, so that a magnet placed on a chunk of the material would levitate above the surface. And its heat capacity – the amount of heat needed to raise their temperature by a given amount – showed a distinctive anomaly at the transition.

But despite decades of effort with a variety of experimental tools, the fourth signature, which can be seen only on a microscopic scale, remained elusive: the way electrons pair up and condense into a sort of electron soup as the material transitions from its normal state to a superconducting state.

Now a research team at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University has finally revealed that fourth signature with precise, high-resolution measurements made with angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy, or ARPES, which uses light to eject electrons from the material. Measuring the energy and momentum of those ejected electrons reveals how the electrons inside the material behave.

In a paper published today in Nature, the team confirmed that the cuprate material they studied, known as Bi2212, made the transition to a superconducting state in two distinct steps and at very different temperatures.

“Now we know what happens at the superconducting transition in very fine detail, and we can think about how to make that happen at higher temperatures,” said Sudi Chen, who led the study while a PhD student at Stanford. “That’s a very practical direction.”

Stanford Professor Zhi-Xun Shen, an investigator with the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES) at SLAC who supervised the research, said, “This is the climax of 15 years of scientific detective work in trying to understand the electronic structure of these materials, and it provides the missing link for a holistic picture of unconventional superconductivity. We knew these materials should produce distinctive spectroscopic signatures as the paired electrons coalesce into a quantum condensate; the amazing thing is that it took so long to find it.”

Unconventional transitions

In conventional superconductors, which were discovered in 1911, electrons overcome their mutual repulsion and form what are known as Cooper pairs, which immediately condense into a sort of electron soup that allows electrical current to travel unimpeded.

But in the unconventional cuprates, scientists have speculated that electrons pair up at one temperature but don't condense until they're cooled to a significantly lower temperature; only at that point does the material become superconducting.

While the details of this transition had been explored with other methods, until now it had not been confirmed with microscopic probes like photoemission spectroscopy that study how matter absorbs light and emits electrons. It’s an important independent measure of how electrons in the material behave.

Shen started his scientific career at Stanford just as the discovery of the new cuprate superconductors was coming to light, and he has devoted more than three decades to unraveling their secrets and improving photoemission spectroscopy as a tool for doing that.

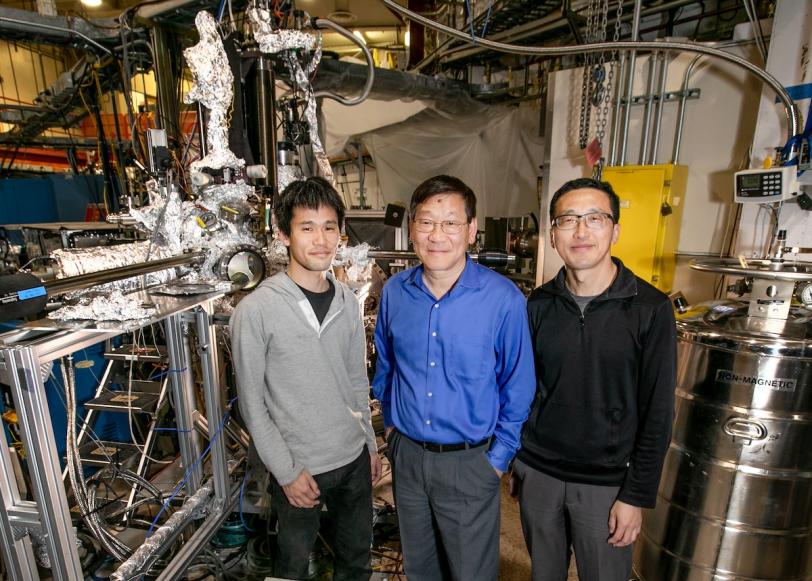

For this study, cuprate samples made by collaborators in Japan were examined at two ARPES setups – one in Shen’s Stanford laboratory, equipped with an ultraviolet laser, and the other at SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) with the help of SLAC staff scientists and longtime collaborators Makoto Hashimoto and Donghui Lu.

Peeling a physics onion

“Recent improvements in the overall performance of those instruments were an important factor in obtaining these high-quality results,” Hashimoto said. “They allowed us to measure the energy of the ejected electrons with more precision, stability and consistency.”

Lu added, “It’s very challenging to get a full understanding of the physics of high-temperature superconductivity. Experimentalists use different tools to probe different aspects of this hard problem, and this provides deeper insights.”

Shen said the long-term study of these unconventional materials has been like peeling layers from an onion to reveal the surprising and interesting physics within.

Now, he said, confirming that the transition to superconductivity occurs in two separate steps “gives us two knobs we can tune to get the materials to superconduct at higher temperatures.”

Sudi Chen is now a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California, Berkeley. Researchers from the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology in Japan, the Lorentz Institute for Theoretical Physics at Leiden University in the Netherlands, and DOE’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory also contributed to this work, which was funded by the DOE Office of Science. SSRL is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

Citation: Su-Di Chen et al., Nature, 26 January 2022 (10.1038/s41586-021-04251-2)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.