SLAC invention could make particle accelerators 10 times smaller

It uses terahertz radiation to power a miniscule copper accelerator structure.

By Manuel Gnida

Particle accelerators generate high-energy beams of electrons, protons and ions for a wide range of applications, including particle colliders that shed light on nature’s subatomic components, X-ray lasers that film atoms and molecules during chemical reactions and medical devices for treating cancer.

As a rule of thumb, the longer the accelerator, the more powerful it is. Now, a team led by scientists at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory has invented a new type of accelerator structure that delivers a 10 times larger energy gain over a given distance than conventional ones. This could make accelerators used for a given application 10 times shorter.

The key idea behind the technology, described in a recent article in Applied Physics Letters, is to use terahertz radiation to boost particle energies.

In today’s accelerators, particles draw energy from a radio-frequency (RF) field fed into specifically shaped accelerator structures, or cavities. Each cavity can deliver only a limited energy boost over a given distance, so very long strings of cavities are needed to produce high-energy beams.

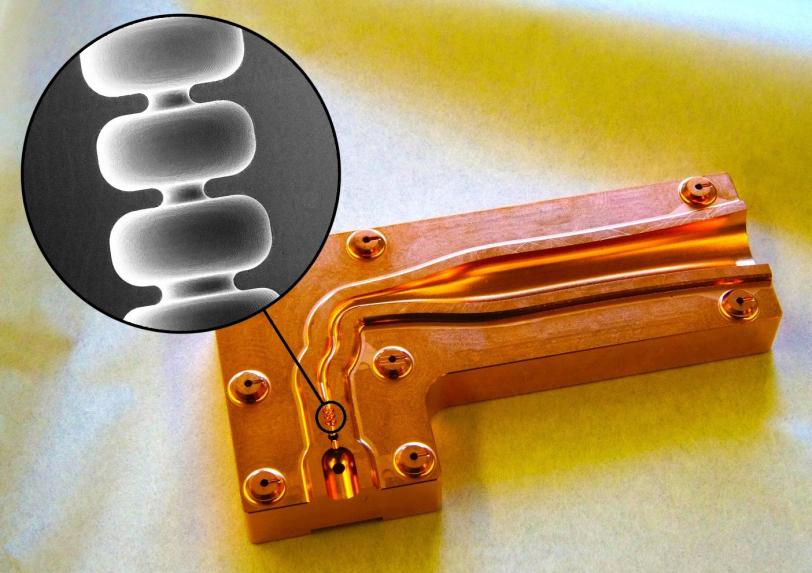

Terahertz and radio waves are both electromagnetic radiation; they differ in their respective wavelengths. Because terahertz waves are 10 times shorter than radio waves, cavities in a terahertz accelerator can also be much smaller. In fact, the one invented in this study was only 0.2 inches long.

One major challenge to building these tiny cavity structures is to machine them very precisely. Over the past few years, SLAC teams developed a way to do just that. Instead of using the traditional process of stacking many layers of copper on top of each other, they built the minute structure by machining two halves and bonding them together.

The new structure also produces particle pulses a thousand times shorter than those coming out of conventional copper structures, which could be used to produce beams that pulse at a higher rate and unleash more power over a given time period.

Next, the researchers are planning to turn the invention into an electron gun – a device that could produce incredibly bright beams of electrons for discovery science, including next-generation X-ray lasers and electron microscopes that would allow us to see in real time how nature works on the atomic level. These beams could also be used for cancer treatment.

Delivering on this potential also requires further development of sources of terahertz radiation and their integration with advanced accelerators, such as the one described in this study. Because terahertz radiation has such a short wavelength, its sources are particularly challenging to develop, and there is little technology available at present. SLAC researchers are pursuing both electron beam and laser-based terahertz generation to provide the high peak powers needed to turn their accelerator research into future real-world applications.

The project was led by SLAC’s Mohamed Othman and Emilio Nanni. The accelerator structure was designed and built at SLAC and tested using a special terahertz radiation source from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Other contributions came from the National Institute for Nuclear Physics (INFN) in Italy. The project was funded by DOE’s Office of Science, including a DOE Office of Science Early Career Research Program award to Nanni, and the National Science Foundation.

Citation: M. Othman et al., Applied Physics Letters, 18 August 2020 (10.1063/5.0011397)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.