Researchers tease out the unique chemical fingerprint of the most aggressive free radical in living things

The technique they used will offer insight into many different chemical reactions.

Free radicals – atoms and molecules with unpaired electrons – can wreak havoc on the body. They are like jilted paramours, destined to wander about in search of another electron, leaving broken cells, proteins and DNA in their wakes.

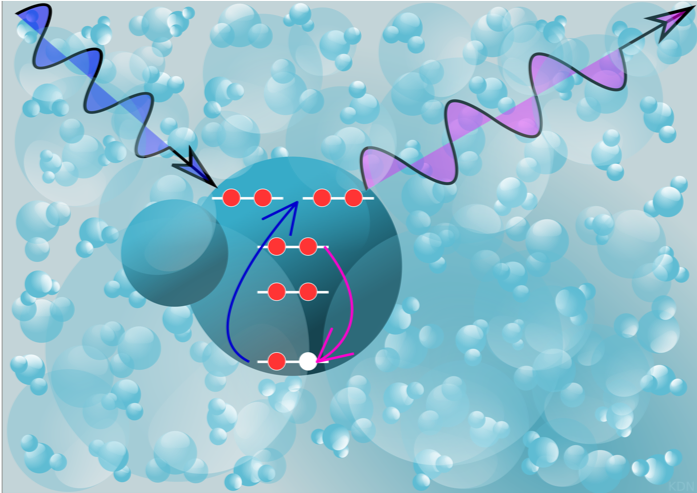

Hydroxyl radicals are the most chemically aggressive of the free radicals, surviving for only trillionths of a second. They form when water, the most abundant molecule in cells, is hit with radiation, causing it to lose an electron. In previous research, a team led by Linda Young, a scientist at the Department of Energy’s Argonne National Laboratory, observed the ultrafast birth of these free radicals, a process with great significance in fields such as sunlight-induced biological damage, environmental remediation, nuclear engineering, and space travel.

Now her team, including researchers from DOE’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, has teased out a unique chemical fingerprint of the hydroxyl, which will help scientists track chemical reactions it instigates in complex biological environments. They published their results in Physical Review Letters in June.

At SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) free-electron laser, the scientists probed the incredibly short-lived hydroxyl radicals with X-ray pulses that last just millionths of a billionth of a second. They illuminated a thin jet of laser-ionized water with X-rays that had the precise energy to excite electrons deep inside the radicals so they jumped up into a specific higher orbit. When the electrons settled back down into their original orbits, a tiny fraction of them emitted X-rays that carried the radical’s unique signature, or spectrum. The team used new theoretical tools to accurately compute these X-ray spectra and decipher the message they contained.

To follow up, the team will investigate what happens in the first moments ionizing radiation breaks apart water with higher time resolution to learn more about the process. Down the road, they hope to study similar processes in alkaline environments that are of interest both fundamentally and for pressing applications such nuclear waste remediation, which requires an understanding of the complex chemistry happening in tanks undergoing constant radiation bombardment.

LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility. This research was funded by the Office of Science. The team also included researchers from the University of Southern California; Northwestern Universityand the University of Chicago in Illinois; Uppsala University in Sweden; Nanyang Technological University in Singapore; DESY, the Hamburg Centre for Ultrafast Imaging and the University of Hamburg in Germany; the Technical University of Denmark; and Sorbonne University and the French National Centre for Scientific Research in France.

Citation: L. Kjellsson et al., Physical Review Letters, 12 June 2020 (10.1103/PhysRevLett.124.236001)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.