Scientists observe ultrafast birth of free radicals in water

What they learned could lead to a better understanding of how ionizing radiation can damage material systems, including cells.

Understanding how ionizing radiation interacts with water—like in water-cooled nuclear reactors and other water-containing systems—requires glimpsing some of the fastest chemical reactions ever observed.

In a new study conducted at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, researchers have witnessed for the first time the ultrafast proton transfer reaction following ionization of liquid water. The findings, published today in Science, are the result of a world-wide collaboration led by scientists at the DOE’s Argonne National Laboratory, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore) and the German research center DESY.

The proton transfer reaction is a process of great significance to a wide range of fields, including nuclear engineering, space travel and environmental remediation. This observation was made possible by the availability of ultrafast X-ray free electron laser pulses, and is basically unobservable by other ultrafast methods. While studying the fastest chemical reactions is interesting in its own right, this observation of water also has important practical implications.

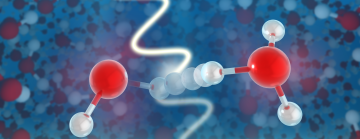

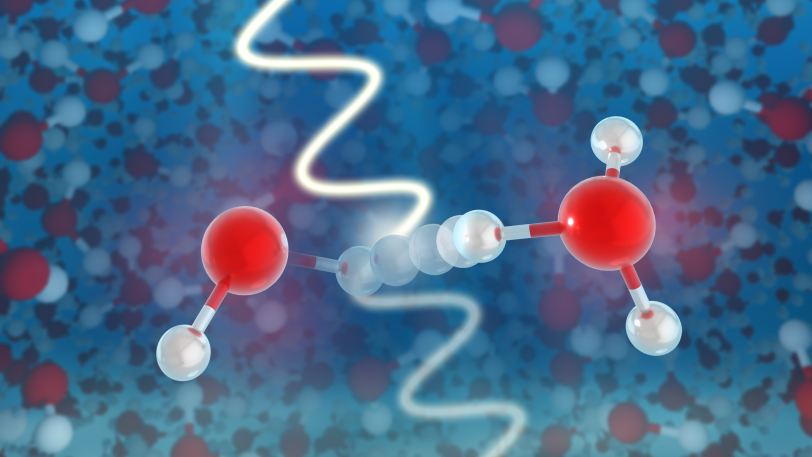

“The truly exciting thing is that we’ve witnessed the fastest chemical reaction in ionized water, which leads to the birth of the hydroxyl radical,” said Argonne distinguished fellow Linda Young, the senior corresponding author of the study. “The hydroxyl radical is itself of considerable importance, as it can diffuse through an organism, including our bodies, and damage virtually any macromolecule including DNA, RNA and proteins.”

By understanding the time scale for the formation of the chemically aggressive hydroxyl radical, and thereby gaining a deeper mechanistic understanding of the radiolysis of water, it may ultimately become possible to develop strategies to suppress this key step which can lead to radiation damage.

Electron ejection

When radiation with sufficient energy hits a water molecule, it triggers a set of virtually instantaneous reactions. First, the radiation ejects an electron, leaving a positively charged water molecule (H2O+) in its wake. H2O+ is extremely short-lived—so short-lived, in fact, that it is virtually impossible to see directly in experiments. Within a fraction of a trillionth of a second, H2O+ gives up a proton to another water molecule, creating hydronium (H3O+) and a hydroxyl (OH) radical.

Scientists had long known of this reaction, with a first sighting in the 1960s when scientists at Argonne first detected the electron ejected from water by radiolysis. However, without a sufficiently fast X-ray probe like that provided by the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) at SLAC, a DOE Office of Science user facility, researchers had no way to observe the residual positively charged ion, the other half of the reaction pair.

“The key to capturing the water in action is the ultrashort X-ray pulses at LCLS. By adjusting the ‘color’ of these X-ray pulses, we can distinguish between the specific ions and molecules that participate,” said SLAC instrument scientist Bill Schlotter, who with Young led the conceptual design of the experiment. “Being part of this highly collaborative and world-class group was just as exciting as watching water molecules dance in slow motion following ionization.”

Freeze-frame technology

The “freeze-frame” technology offered by LCLS gave researchers the first opportunity to watch the time evolution of the hydroxyl radical. While according to Young, the researchers would have liked to isolate the spectroscopic signature of the H2O+ radical cation as well, its lifetime is so short that its presence was only inferred from the OH spectroscopy measurements.

The ultrafast proton transfer that creates the hydroxyl radical gives rise to a special spectroscopic signature that indicates the rise of the hydroxyl radical and is a “time stamp” for the initial creation of the H2O+. According to Young, the spectra of both species are accessible because they exist in a “water window” where liquid water does not absorb light.

“The major accomplishment here is the development of a method to watch elementary proton transfer reactions in water and to have a clean probe for the hydroxyl radical,” Young said. “No one knew the time scale of proton transfer, so now we’ve measured it. No one had a way to follow the hydroxyl radical in complex systems on ultrafast timescales, and now we have a way to do that as well.”

Understanding the formation of the hydroxyl radical could be of particular interest in aqueous environments containing salts or other minerals that might, in turn, react with ionized water or its byproducts. Such environments could include nuclear waste repositories or other places in need of environmental remediation.

The development of the theory behind the experiment was led by Robin Santra of the Center for Free-Electron Laser Science at DESY in Germany. Santra showed that through ultrafast X-ray absorption, scientists could detect the structural dynamics—both in terms of electron and nuclear motion—near the ionization and proton transfer site.

Argonne’s Center for Nanoscale Materials, a DOE Office of Science user facility, was used to characterize the water jet before the experiment at LCLS. In addition to Argonne, DESY, SLAC and NTU Singapore, several other institutions collaborated on the study. They included Uppsala University in Sweden, the Technical University of Denmark, and France’s CNRS. The Argonne and SLAC portions of the research were funded by DOE’s Office of Science.

This article is based on a press release from Argonne. See also stories by DESY and NTU.

Citation: Z.H. Loh et al., Science, 10 January 2020 (10.1126/science.aaz4740)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.