Looping X-rays to produce higher quality laser pulses

A proposed device could expand the reach of X-ray lasers, opening new experimental avenues in biology, chemistry, materials science and physics.

Ever since 1960, when Theodore Maiman built the world’s first infrared laser, physicists dreamed of producing X-ray laser pulses that are capable of probing the ultrashort and ultrafast scales of atoms and molecules.

This dream was finally realized in 2009, when the world’s first hard X-ray free-electron laser (XFEL), the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, produced its first light. One limitation of LCLS and other XFELs in their normal mode of operation is that each pulse has a slightly different wavelength distribution, and there can be variability in the pulse length and intensity. Various methods exist to address this limitation, including ‘seeding’ the laser at a particular wavelength, but these still fall short of the wavelength purity of conventional lasers.

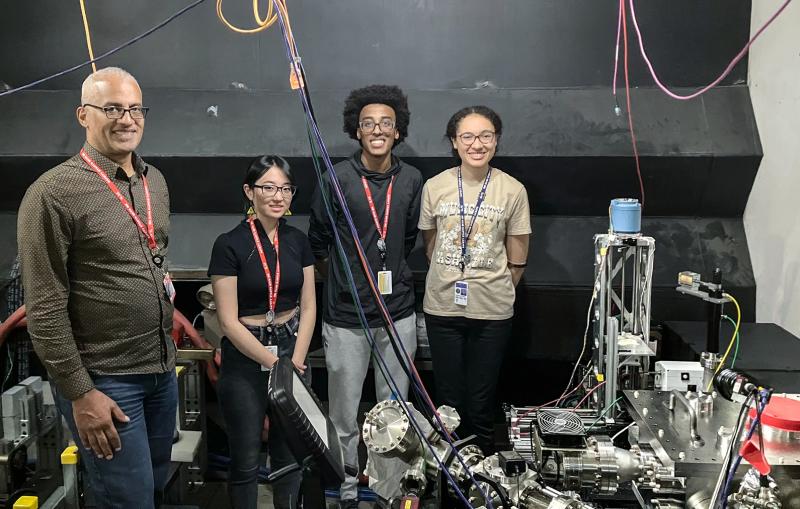

Now, SLAC researchers are developing a compact device that could create higher quality X-ray pulses at LCLS with an approach inspired by optical lasers. The new instrument could expand the reach of X-ray lasers, opening new experimental avenues in areas such as biology, chemistry, materials science and physics. Their recent findings were published last week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“As X-ray science continues to advance over the next decades, we need to start thinking about better technologies,” says co-author Claudio Pellegrini, a distinguished professor emeritus of physics at UCLA and adjunct professor at SLAC whose work laid the scientific groundwork for the development of LCLS. “The current quality of our X-ray pulses might work for now, but in order to keep moving forward in the field we have to continuously imagine new and better ways of creating better X-ray pulses.”

In the loop

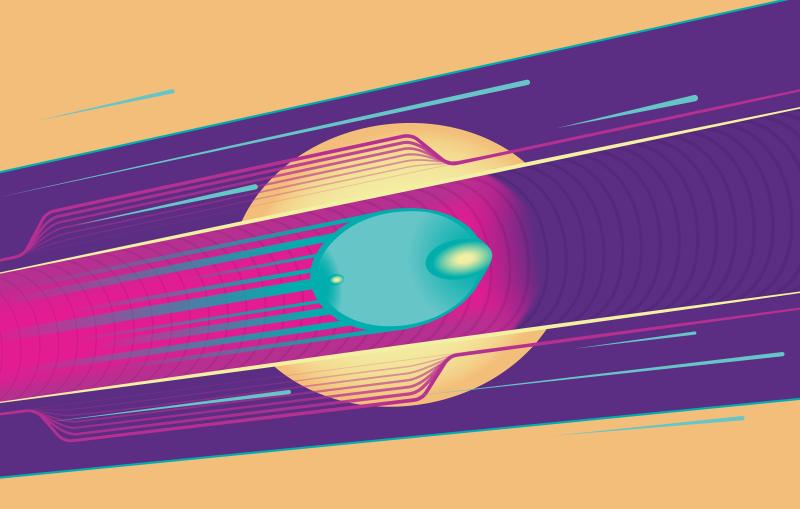

At the heart of almost every optical laser lies an oscillator, which ushers photons through a series of mirror reflections surrounding what is known as the gain medium, a material used to amplify the light, producing an ever more intense beam at each loop. Eventually, a monochromatic, or single color, fully coherent laser beam is released. The goal is to design a laser oscillator that would work with X-rays, a longstanding challenge in the laser field.

In this proposed device, the researchers begin by sending an initial X-ray pulse from LCLS down the beamline. This pulse passes through a liquid jet, where it creates excited atoms that produce a small amount of emitted radiation in one distinct color moving in the same direction. This laser pulse is reflected through a series of mirrors arranged in a loop. After completing the loop, the pulse joins up with a second X-ray pulse from LCLS producing an even brighter laser pulse, which then takes the same loop. The process is repeated several times, and with each loop the laser pulse intensifies and becomes more coherent. During the last loop, one of the mirrors is quickly switched allowing this laser pulse to exit.

“The result will be a fully coherent X-ray laser pulse that is brighter and cleaner than that created with an XFEL alone,” says lead author and SLAC research associate Alex Halavanau.

Small but mighty

The project is part of a three-year effort that recently received DOE funding. As the team continues to develop the device, they will begin testing it at LCLS in the upcoming experimental run.

“The goal is to build a compact instrument at LCLS that provides the highest quality X-ray laser pulses for probing matter at the level of atoms and molecules with unprecedented precision,” says co-author Uwe Bergmann, a distinguished staff scientist at SLAC.

“There are two other ongoing projects at LCLS, XFELO and RAFEL, that aim to provide precision X-ray laser pulses with an oscillator,” Pellegrini adds, referring to projects that are under development in collaboration with the DOE's Argonne National Laboratory and industrial partners through DOE funding. “Our compact device will complement these much larger instruments and their properties. This research will provide exciting opportunities at LCLS for the coming decades.”

LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility. This research was supported by the Office of Science.

Citation: A. Halavanau et al., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 22 June 2020 (10.1073/pnas.2005360117)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.