Radio waves detect particle showers in a block of plastic

A cheap technique could detect neutrinos in polar ice, eventually allowing researchers to expand the energy reach of IceCube without breaking the bank.

By Ali Sundermier

When neutrinos crash into water molecules in the billion-plus tons of ice that make up the detector at the IceCube Neutrino Observatory in Antarctica, more than 5,000 sensors detect the light of subatomic particles produced by the collisions. But as one might expect, these grand-scale experiments don’t come cheap.

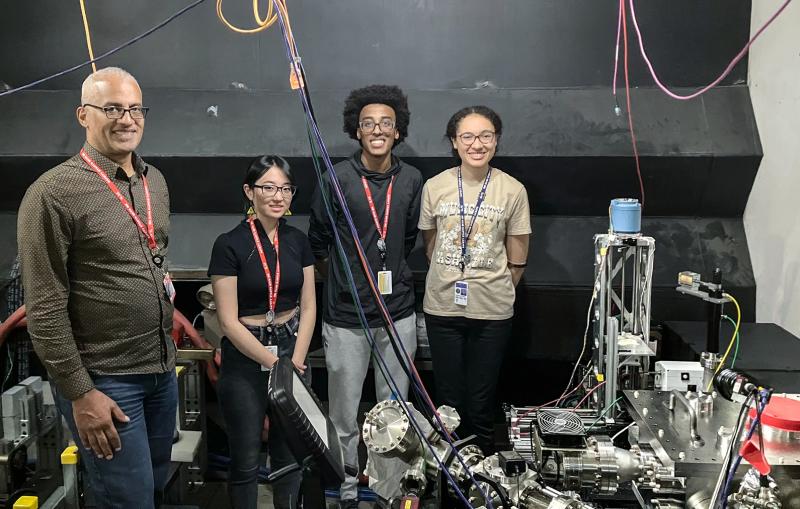

In a paper recently accepted by Physical Review Letters, an international team of physicists working at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory demonstrated an inexpensive way to expand IceCube’s neutrino search.

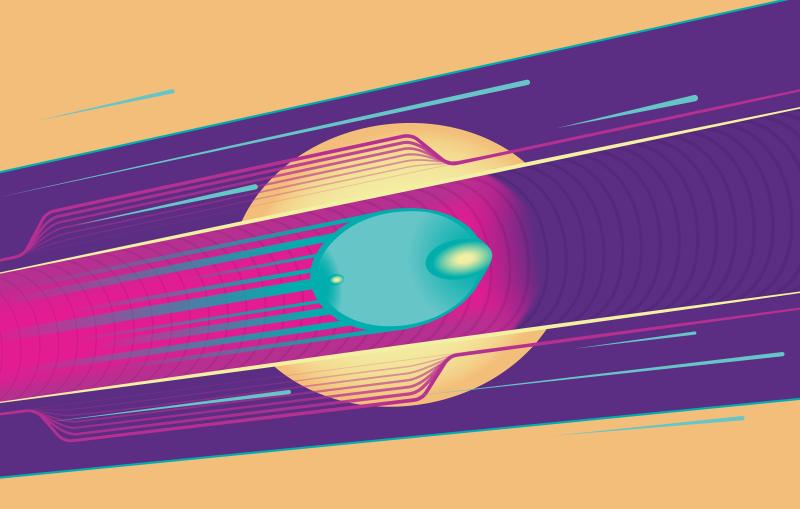

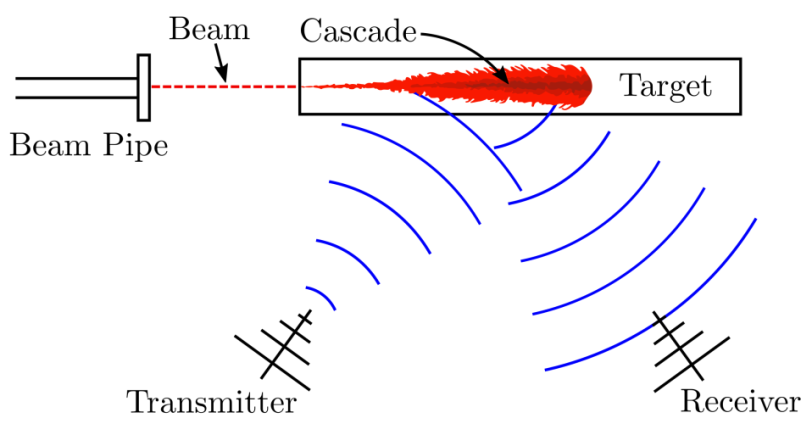

The researchers directed an electron beam diverted from SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) into a large block of plastic to mimic neutrinos colliding with ice. When a neutrino interacts with ice, it produces a cascade of high-energy particles that leave a trail of ionization in their wake. The same is true for electron collisions in the plastic.

To detect those ionization trails, the team used an antenna to bounce radio waves off them. This created radar echoes that were picked up by additional antennas. It was the first time researchers have been able to detect radar echoes from a particle cascade.

These echoes carry information about neutrinos in an energy range that could bridge the gap between the lower-energy neutrinos that IceCube detects and the higher-energy neutrinos detected by other in-ice and balloon-based detectors. To follow up, the researchers hope to use a similar set-up to detect neutrinos with a radio echo in Antarctic ice. If successful, the technique could eventually allow researchers to expand the energy reach of IceCube without breaking the bank.

LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility. The research, carried out at the End Station A test beam (ESTB) at SLAC, was led by Steven Prohira, a postdoctoral scholar at Ohio State University. Carsten Hast, a physicist at SLAC, was instrumental in setting up the experiment. The team also included researchers from the University of Kansas; California Polytechnic State University; the University of Wisconsin-Madison; Vrije Universiteit Brussel in Belgium; National Research Nuclear University, Moscow Engineering Physics Institute in Russia; and National Taiwan University. Major funding came from the DOE Office of Science.

Citation: S. Prohira et al., Physical Review Letters, accepted 17 January 2020

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.