Theorists probe the relationship between ‘strange metals’ and high-temperature superconductors

Computer simulations yield a much more accurate picture of these states of matter.

By Glennda Chui

Strange metals make interesting bedfellows for a phenomenon known as high-temperature superconductivity, which allows materials to carry electricity with zero loss.

Both are rule-breakers. Strange metals don’t behave like regular metals, whose electrons act independently; instead their electrons behave in some unusual collective manner. For their part, high-temperature superconductors operate at much higher temperatures than conventional superconductors; how they do this is still unknown.

In many high-temperature superconductors, changing the temperature or the number of free-flowing electrons in the material can flip it from a superconducting state to a strange metal state or vice versa. Scientists are trying to find out how these states are related, part of a 30-year quest to understand how high-temperature superconductors work so they can be developed for a host of potential applications, from maglev trains to perfectly efficient power transmission lines.

In a paper published today in Science, theorists with the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES) at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory report that they have observed strange metallicity in the Hubbard model. This is a longstanding model for simulating and describing the behavior of materials with strongly correlated electrons, meaning that the electrons join forces to produce unexpected phenomena rather than acting independently.

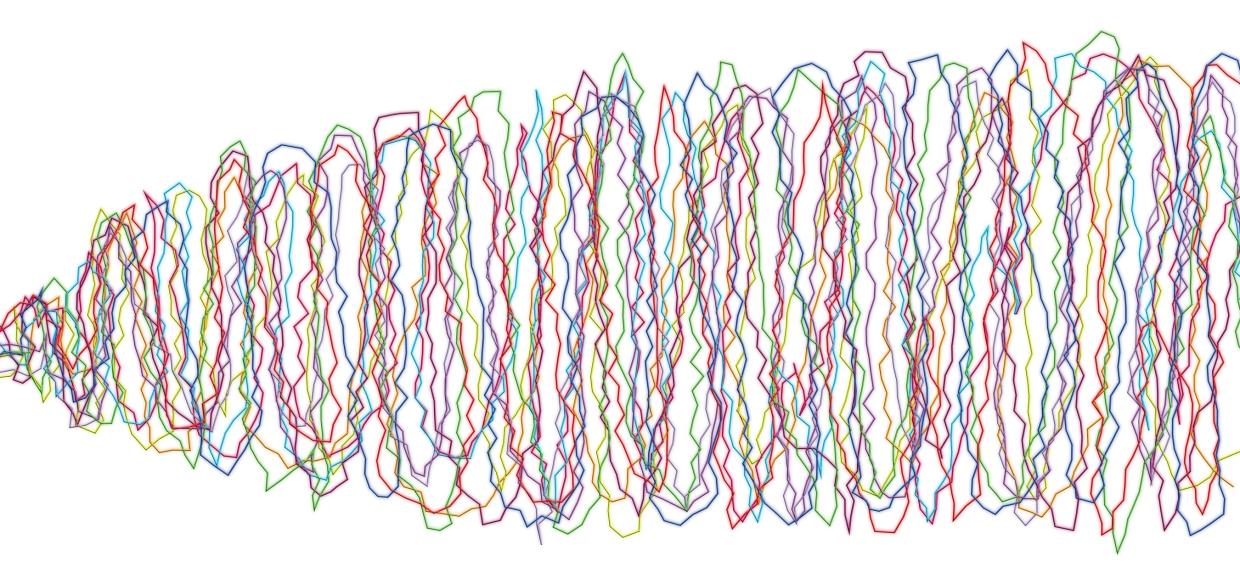

Although the Hubbard model has been studied for decades, with some hints of strange metallic behavior, this was the first time strange metallicity had been seen in Monte Carlo simulations, in which billions of separate and slightly different calculations are averaged to produce an unbiased result. This is important because the physics of these systems can change drastically and without warning if any approximations are introduced.

The SIMES team was also able to observe strange metallicity at the lowest temperatures ever explored with an unbiased method – temperatures at which the conclusions from their simulations are much more relevant for experiments.

The scientists said their work provides a foundation for connecting theories of strange metals to models of superconductors and other strongly correlated materials.

The research was led by Edwin Huang, a Stanford University PhD student in the group of SIMES Director and study co-author Thomas Devereaux. SIMES researcher Brian Moritz and Stanford physics student Ryan Sheppard also contributed to the study, which was funded by the DOE Office of Science. Computational work was performed on Stanford’s Sherlock computing cluster and on resources of the DOE’s National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center.

Citation: Edwin Huang et al., Science, 22 November 2019 (10.1126/science.aau7063)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.