In brief: Researchers home in on extremely rare nuclear process

The complete data from the EXO-200 experiment provide new information on neutrinoless double beta decay and set the stage for future experiments that will search for the hypothetical process.

By Manuel Gnida

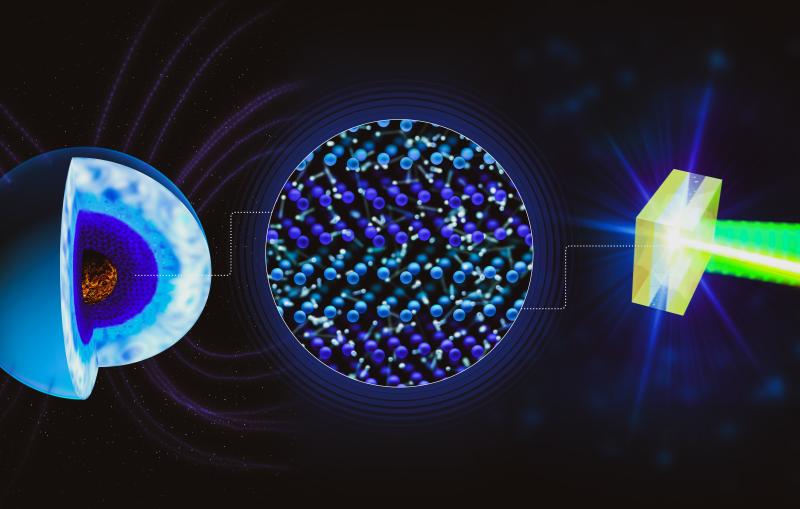

A hypothetical nuclear process known as neutrinoless double beta decay ought to be among the least likely events in the universe. Now the international EXO-200 collaboration, which includes researchers from the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, has determined just how unlikely it is: In a given volume of a certain xenon isotope, it would take more than 35 trillion trillion years for half of its nuclei to decay through this process – an eternity compared to the age of the universe, which is “only” 13 billion years old.

If discovered, neutrinoless double beta decay would prove that neutrinos – highly abundant elementary particles with extremely small mass – are their own antiparticles. That information would help researchers determine how heavy neutrinos actually are and how they acquire their mass. Although the EXO-200 experiment did not observe the decay, its complete data set, published on the arXiv repository and accepted for publication in Physical Review Letters, defined some of the strongest limits yet for the decay’s half-life and for the mass neutrinos may have.

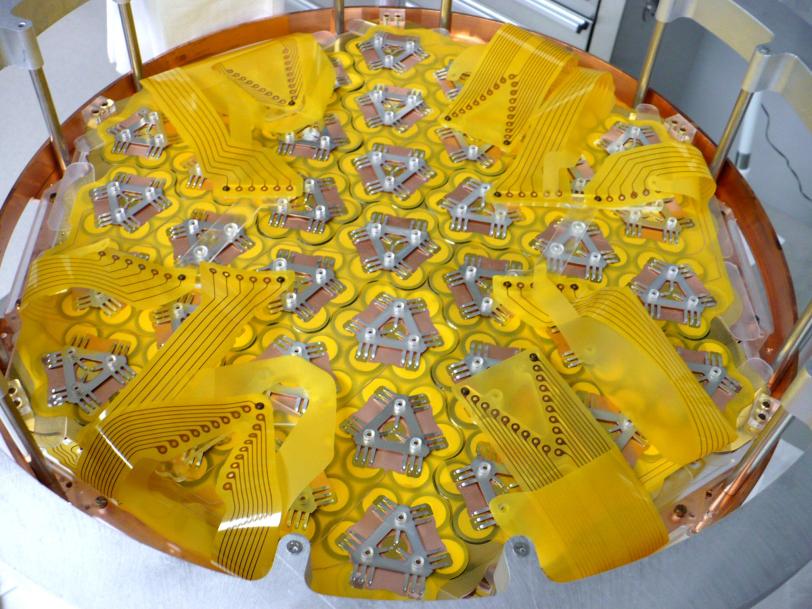

EXO-200 operated at the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) in New Mexico from 2011 to 2018. Within its first months of operations, it discovered another rare process: the two-neutrino double beta decay of the same xenon isotope. EXO-200 was an important precursor for next-generation experiments, such as the proposed nEXO, that would have a much better chance of discovering the neutrinoless decay.

U.S. funding for EXO-200 comes from the DOE Office of Science and the National Science Foundation. The data analysis was partially done using resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), a DOE Office of Science user facility. Martin Breidenbach is the principal investigator of SLAC’s EXO-200 team.

Citation: EXO-200 Collaboration, accepted in Physical Review Letters (arXiv:1906.02723v2)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit energy.gov/science.