In brief: Record-shattering underwater sound

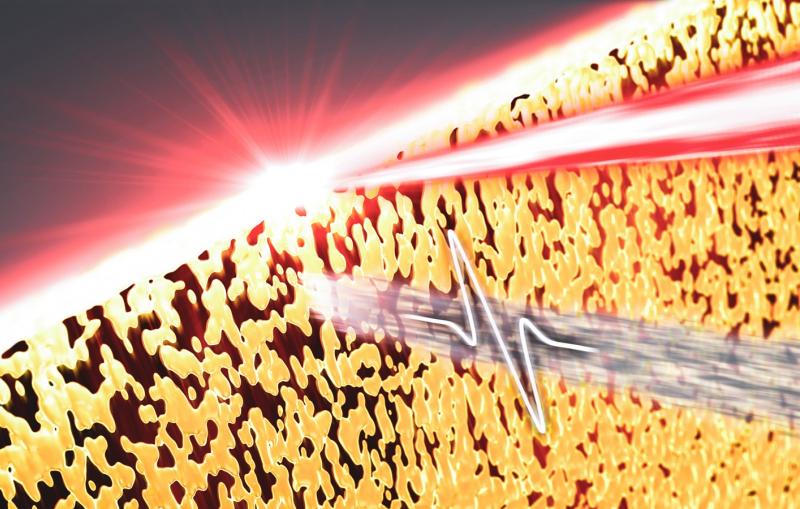

Researchers produced an underwater sound with an intensity that eclipses that of a rocket launch while investigating what happens when they blast tiny jets of water with X-ray laser pulses.

A team of researchers has produced a record-shattering underwater sound with an intensity that eclipses that of a rocket launch. The intensity was equivalent to directing the electrical power of an entire city onto a single square meter, resulting in sound pressures above 270 decibels. The team, which included researchers from the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, published their findings on April 10 in Physical Review Fluids.

Using the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), SLAC’s X-ray laser, the researchers blasted tiny jets of water with short pulses of powerful X-rays. They learned that when the X-ray laser hit the jet, it vaporized the water around it and produced a shockwave. As this shockwave traveled through the jet, it created copies of itself, which formed a “shockwave train” that alternated between high and low pressures. Once the intensity of underwater sound crosses a certain threshold, the water breaks apart into small vapor-filled bubbles that immediately collapse. The pressure created by the shockwaves was just below this breaking point, suggesting it was at the limit of how loud sound can get underwater.

A better understanding of these trains is essential to creating new techniques that ward off damage in miniature samples that are suspended in water jets to allow their atomic-scale structure to be measured. This could advance research in areas such as biology and materials science, leading to more effective drugs and more efficient materials.

The team was led by Gabriel Blaj, a staff scientist at SLAC and Stanford University, and Claudiu Stan, at Rutgers University Newark. It also included researchers from the Stanford PULSE Institute and the Paul Scherrer Institute in Switzerland. LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility. This work was supported by the Department of Energy’s Office of Science and Chemical Sciences, Geosciences and Biosciences Division.

Citation: Gabriel Blaj et al., Physical Review Fluids, 10 April 2019 (10.1103/PhysRevFluids.4.043401)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.