X-Ray Laser Scientists Develop a New Way to Watch Bacteria Attack Antibiotics

The researchers observed how an enzyme from drug-resistant tuberculosis bacteria damages an antibiotic molecule. The new technique provides a powerful tool to examine changes in biological molecules as they happen.

By Amanda Solliday

Tuberculosis, a lung disease that spreads in the air through coughs or sneezes, now kills more people worldwide than any other infectious agent, according to the World Health Organization’s latest global tuberculosis report. And in hundreds of thousands of cases each year, treatment fails because the bacteria that cause Tb have become resistant to antibiotics.

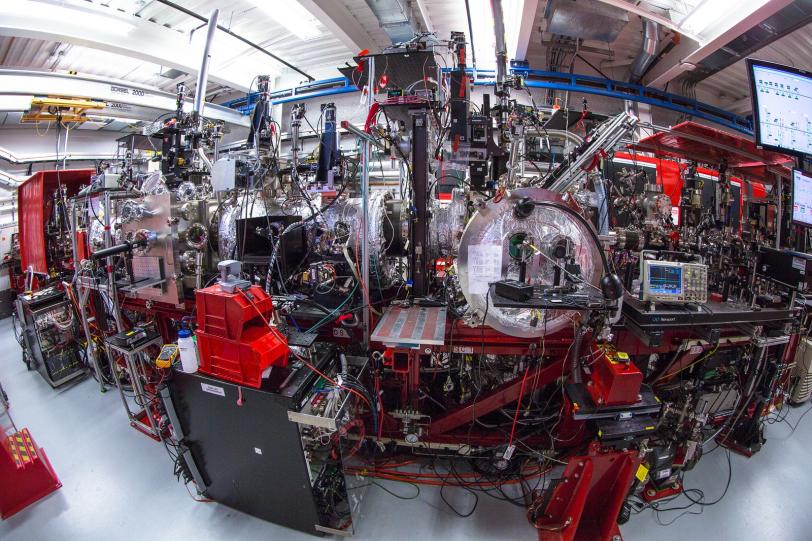

Now an international team of researchers has found a new way to investigate how Tb bacteria inactivate an important family of antibiotics: They watched the process in action for the first time using an X-ray free-electron laser, or XFEL.

In experiments at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, they mixed an antibiotic with an enzyme called beta-lactamase that Tb bacteria use, and then watched in real time as the enzyme attacked the antibiotic to deactivate it.

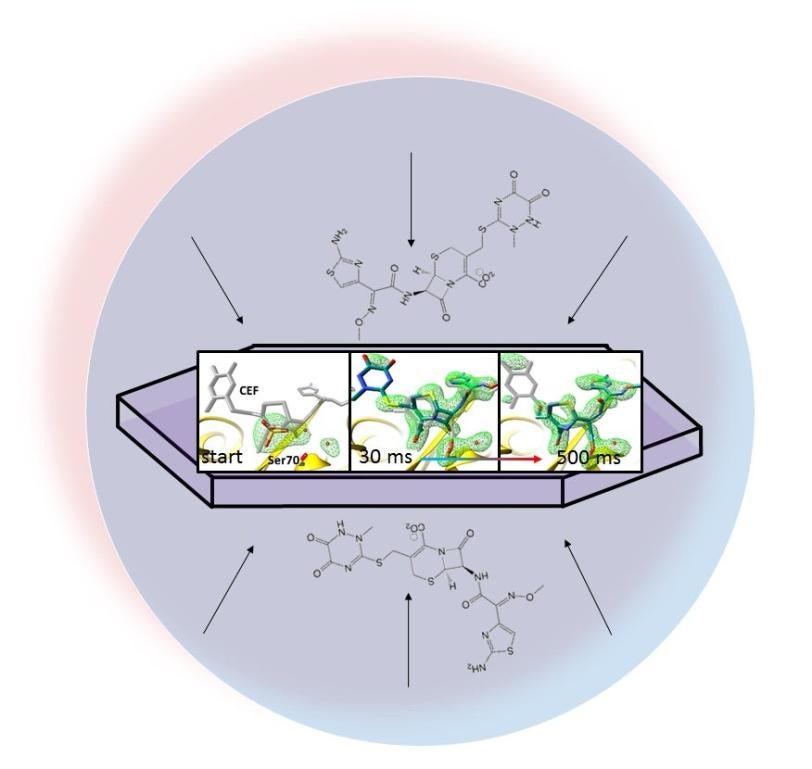

The researchers’ method, called mix-and-inject serial crystallography, takes advantage of the brilliant, ultrafast pulses produced by SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS). X-ray snapshots taken 30 milliseconds to 2 seconds after the reaction began showed lactamase binding to the antibiotic, ceftriaxone, and bursting one of its chemical bonds.

The results of the experiment were published today in BMC Biology.

“This proof-of-concept study shows that we’re able to see the shape and intermediate stages of the molecules during the process,” says Marius Schmidt, a University of Wisconsin Milwaukee professor who led the experiment. “After decades of trying other techniques in the field of crystallography, the technology is here.”

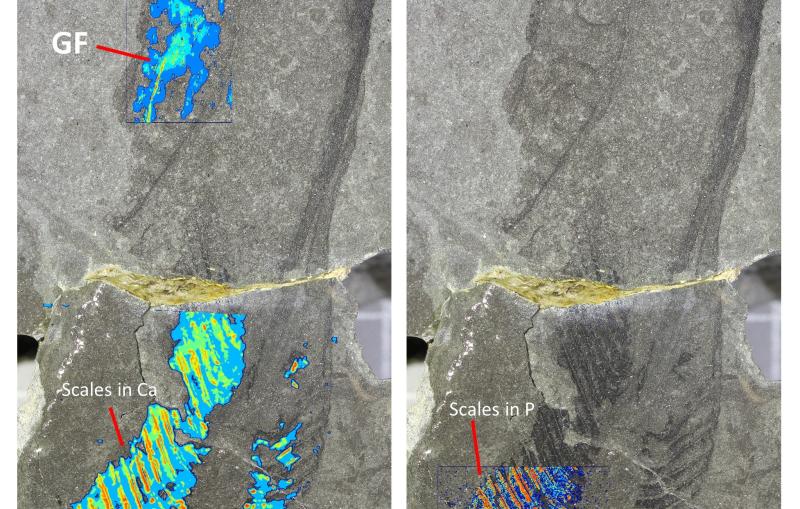

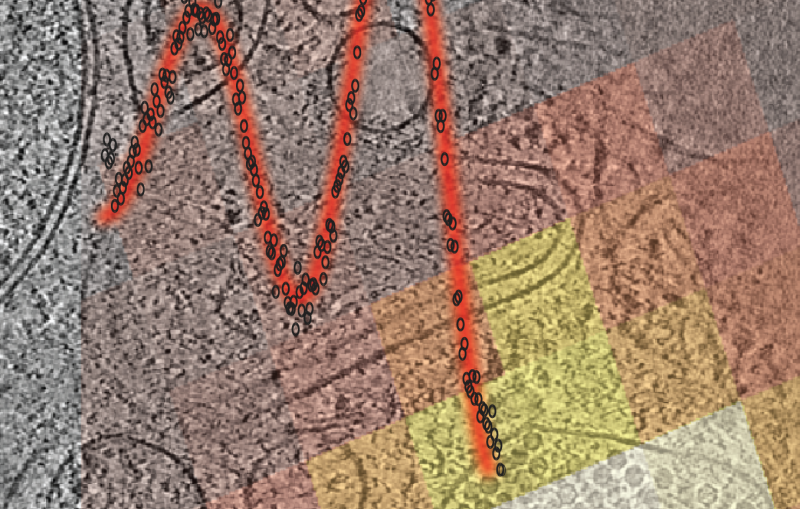

In crystallography, scientists form a crystal from many copies of a protein and hit the crystal with X-rays to produce a diffraction pattern on a detector, which reveals the protein’s atomic structure. This structure is key to understanding how enzymes and other proteins function.

In the past this only worked with relatively large crystals, which have limited value in this method because the solution containing the antibiotic would take a long time to diffuse into the crystal and react with the enzyme. It is important that the diffusion is faster than the reaction, so that the many protein molecules in the crystal start the chemical process together.

But LCLS and other XFELs have such intense beams that they can capture diffraction patterns from much tinier crystals, a millionth of a meter across or less, Schmidt said, so the antibiotic can get to the enzyme quickly, and the reaction can be recorded with X-rays.

“While there have been elegant studies to observe protein motions with light-induced changes, our work illustrates that a larger class of proteins, namely enzymes, can be investigated in a time-resolved fashion at LCLS and other XFELs,” says Jose Olmos, a doctoral student at Rice University who is one of the principal authors of the publication.

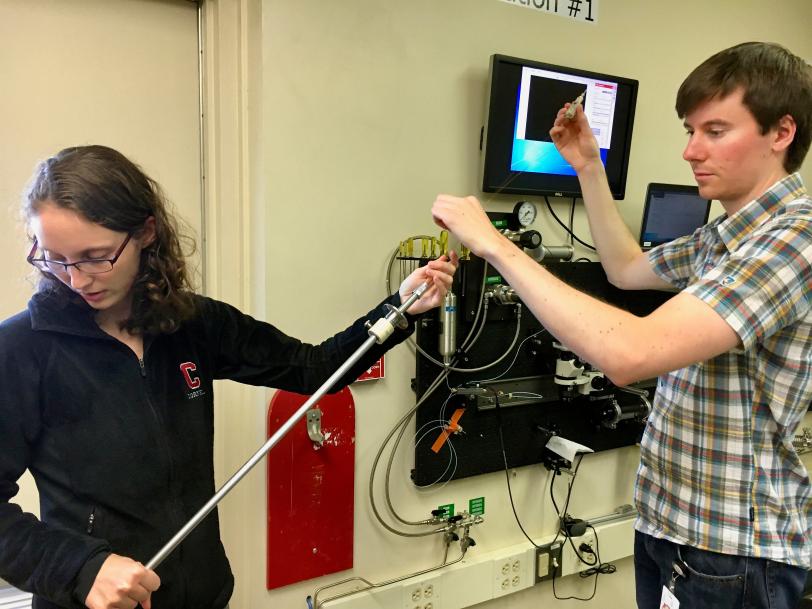

In this study, the research team delivered tiny crystals of beta-lactamase while mixing them with the antibiotic just fractions of a second before they were hit with X-ray pulses.

The team took millions of X-ray snapshots during the reaction and stitched them together to create a map that shows changes in the three-dimensional structure of the antibiotic as it interacts with the enzyme at room temperature.

“For structural biologists, this is how we learn exactly how biology functions,” says Mark Hunter, staff scientist at SLAC and co-author on the study. “We decipher a molecule’s structure at a certain point in time, and it gives us a better idea of how the molecule works.”

In future experiments, taking even more snapshots during the course of the reaction could provide greater detail of the structure and chemical behavior of lactamase. With more information scientists could manipulate the design of antibiotics to prevent such attacks. The experimental method could also be applied to learn the fine details of other types of biological processes where enzymes initiate or steer reactions.

“There’s a large amount of excitement building over this method, because it opens up this new time realm for structural biologists,” Hunter says. Previous work using this technique captured the flipping of an RNA “switch,” important for studies into retroviruses and cancer.

The scientists plan to use the method to look at additional antibiotics. They also intend to take advantage of higher repetition rates – more rapid firing of X-ray pulses – expected at a future upgrade to LCLS and at the recently opened European XFEL. This will allow scientists to capture the data they need in just minutes, compared to days. They could also take more closely spaced snapshots of the reactions, which could give an even more complete picture of the swift chemistry as it happens.

LCLS is a DOE Office of Science User Facility.

The National Science Foundation’s Biology with X-ray Lasers (BioXFEL) Science and Technology Center provided the collaborative framework for this research. In addition to SLAC and the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, the project included scientists from Arizona State University, Cornell University, Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY), GlaxoSmithKline, Hamburg Center for Ultrafast Imaging, DOE’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Max Planck Institute for Biochemistry, Milwaukee School of Engineering, Rice University, Seoul National University, University of Hamburg, University of New York Buffalo and 4Marbles, Inc.

Funding for this work came from the DOE Office of Science, Biodesign Center for Applied Structural Discovery at Arizona State University, Helmholtz Association, National Institutes of Health, and the National Science Foundation.

Citation: Olmos et al., BMC Biology, 31 May 2018 (10.1186/s12915-018-0524-5)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.