Scientists See Molecules ‘Breathe’ in Remarkable Detail

The research team was able to watch energy from light flow through atomic ripples in a molecule. Such insights may provide new ways to develop a class of materials that improve efficiency and reduce the size of solar cells and memory storage devices.

By Amanda Solliday

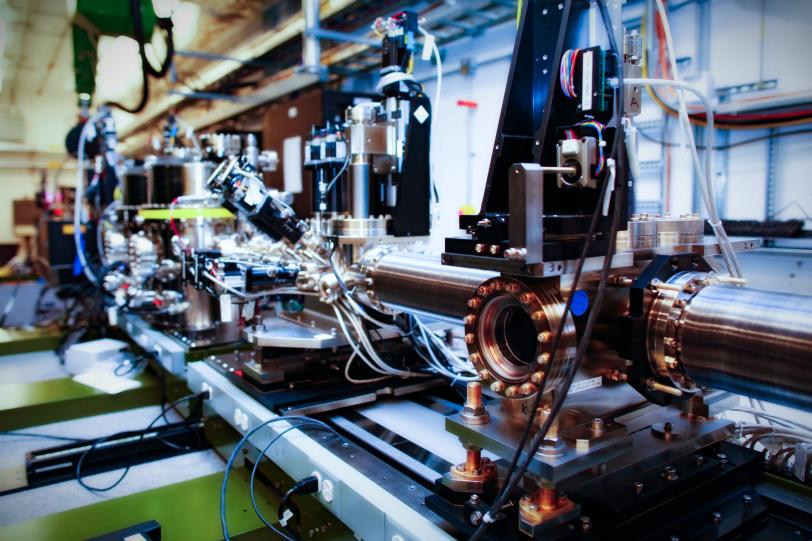

In a milestone for studying a class of chemical reactions relevant to novel solar cells and memory storage devices, an international team of researchers working at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory used an X-ray laser to watch “molecular breathing” – waves of subtle in-and-out motions of atoms – in real time and unprecedented detail.

These ripples of motion, seen with SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), allowed the team to study how energy is exchanged between light and electrons and leads to tension and eventually motion of atoms in an iron-based molecule that’s a model for transforming light to electric energy and switchable tiny molecular magnets.

In a paper published in Nature Communications, the research team said these high fidelity, real-time measurements of ultrafast energy redistribution can provide key information to understand the function of many chemical, physical and biological light-induced phenomena.

“It’s a significant leap in experiment sensitivity that now allows us to see more of what’s happening,” says Diling Zhu, staff scientist at SLAC. “We’re zooming into the details of molecules as we achieve better and better resolution in both space and time.”

The molecule they studied consists of a central iron atom attached to three double-ringed structures known as bipyridines.

To see it “breathe,” the scientists first hit the molecule with laser light and immediately followed up with an X-ray laser pulse to examine any changes that took place.

The laser light excited an electron in the central iron atom, which was transferred to one of the attached bipyridine structures. When the electron returned to the iron atom 100 femtoseconds, or quadrillionths of a second, later, it flipped the magnetism of the iron. This caused the molecule to expand, setting off a breath-like oscillation through the entire structure.

Previous measurements in experiments with optical lasers had indirectly revealed these motions, and it was suspected that bending of the bipyridine attachments contributed to the molecular motion.

But this experiment using more direct signals from X-rays showed that this explanation was incorrect. With each X-ray pulse lasting just 50 femtoseconds, the team could observe the electronic excitation by light and the following breathing process at much shorter intervals than ever before and obtain a more complete picture in real time.

Researchers hope that gained insights from molecular breathing will help them improve technologies such as dye-sensitized solar cells and memory storage.

Sensitized solar cells are a promising future alternative for cheap but efficient devices, but their light absorbing dyes often contain expensive rare metals like ruthenium. Scientists would like to use cheaper iron-based compounds instead, but magnetic switching that induces the molecular breathing stops the flow of electrical current across a solar cell.

“We see two competing processes in the molecule and their relation to molecular structure. With this information, we may find ways to change the molecular structure in order to favor the usable process for potential technical applications,” says Henrik Lemke, formerly a staff scientist at SLAC and now at SwissFEL’s Paul Scherrer Institute in Switzerland. Lemke is lead author of the study, which also included researchers from Sweden, Denmark, Italy, and France, as well as from SLAC.

“For other applications, the switch is actually desirable, so we could create a molecular memory system,” Lemke adds. “In memory storage devices, a reversible process could enable us to write and store data with the material.”

The experiment marks a significant step forward in the capability to visualize molecular dynamics at LCLS's X-ray Pump Probe instrument, which was first commissioned in 2010. To generate sharper images of the molecular motion, scientists at LCLS have developed new methods for delivering samples into the path of the X-ray laser beam, as well as special data analysis techniques to account for various fluctuations that can blur the experiment.

The improvements also mean researchers are now able to collect higher quality data in less time. Scientists at LCLS can now acquire information that may have taken weeks to collect before in just a few minutes.

LCLS is a DOE Office of Science User Facility.

Citation: Lemke et al., Nature Communications, 24 May 2017 (10.1038/ncomms15342)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.