Cutting-edge experiments reveal ‘hidden’ details in transforming material

Using SLAC’s LCLS for one of the first studies of its kind, researchers discover surprising behaviors of a complex material that could have important implications for designing faster microelectronic devices.

By Carol Tseng

Phase changes are central to the world around us. Probably the most familiar example is when ice melts into water or water boils into steam, but phase changes also underlie heating systems and even digital memory, such as that used in smartphones.

Triggered by pulses of light or electricity, some materials can switch between two different phases that represent binary code 0s and 1s to store information. Understanding how a material transforms from one state or phase to another is key to tailoring materials with specific properties that could, for instance, increase switching speed or operate at lower energy costs.

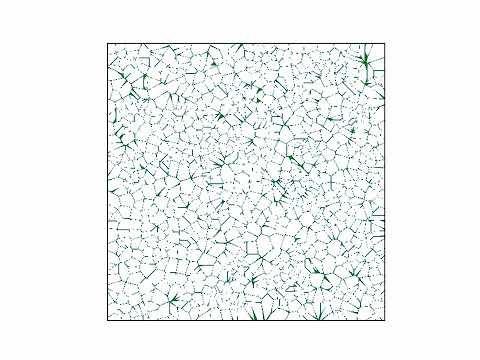

Yet researchers have never been able to directly visualize how these transformations unfold in real time. We often assume materials are perfect and look the same everywhere, but “part of the challenge is that these processes are often heterogeneous, where different parts of the material change in different ways, and involve many different length scales and timescales,” said Aaron Lindenberg, co-author and SLAC and Stanford University professor.

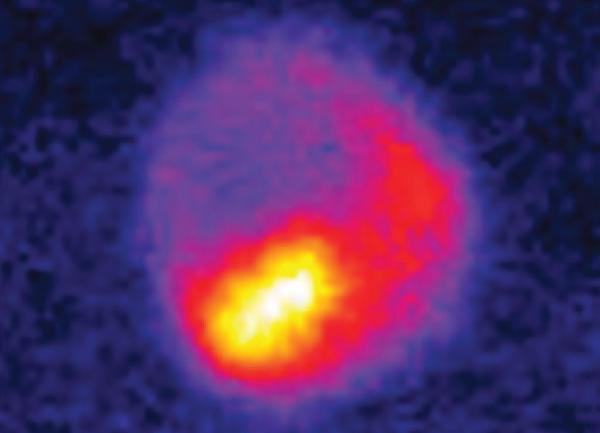

In a groundbreaking study, researchers at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and colleagues used an emerging technique called X-ray photon correlation spectroscopy (XPCS) at the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) to probe phase transformations in a complex structure made up of lead titanate and strontium titanate layers. “This material is poised between multiple states, forming a kind of frustrated system that is highly reconfigurable at the atomic and nanoscale,” said Lindenberg. “A single pulse of light switches it into another crystalline structure known as a ‘supercrystal’.”

What they found challenged conventional wisdom: The time over which the transformation process occurs lasted up to one hundred thousand times longer than previously thought. They also found the transformation proceeded heterogeneously and were able to tie the motion of the boundaries between phases to the much longer transformation timescale.

The research team from SLAC, Stanford University, The Pennsylvania State University, Argonne National Laboratory, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Indian Institute of Science, University of California, Berkeley, and Rice University published their findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

SLAC and Stanford University professorThrough this approach, we could visualize and uncover details that we were blind to when using conventional approaches."

SLAC's high-speed electron camera uncovers a new 'light twisting' behavior in an ultrathin material

Also from Aaron Lindenberg:

SLAC's high-speed electron camera uncovers a new 'light twisting' behavior in an ultrathin material

Using SLAC’s instrument for ultrafast electron diffraction (MeV-UED), researchers discovered how an ultrathin material can circularly polarize light. This discovery sets up a promising approach to manipulate light for applications in optoelectronic devices.

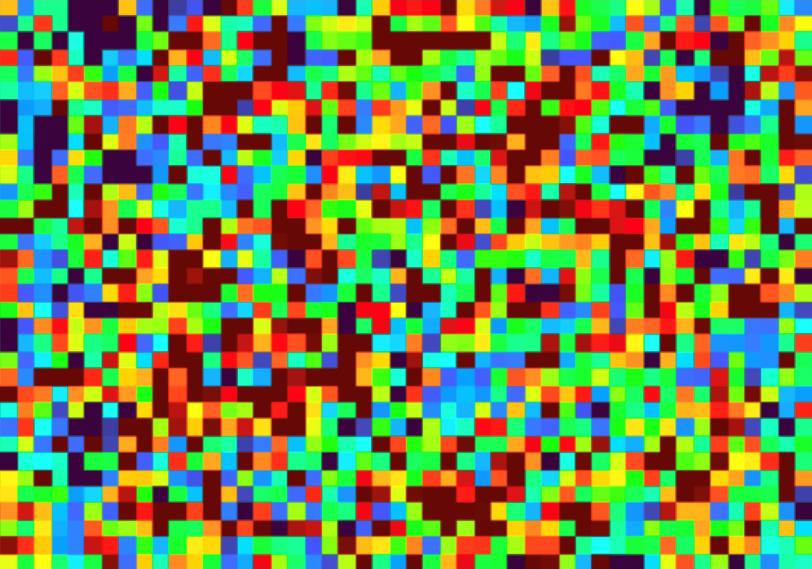

The team initially set out to investigate the possibilities for using XPCS to study in more detail how phases transition from one to the other. The technique involves shooting a single pulse of visible light, called the pump, at a material to trigger a transition and tracking the transformation with subsequent X-ray pulses, called the probe, at various delayed timed intervals. The pattern from the X-ray light scattered by the sample – a speckle pattern – consists of seemingly random regions of bright and dark pixels that encode information about how the sample transforms. The researchers then repeat this “pump-probe" method in other areas around the sample. Compared with previous studies, XPCS paints a more detailed picture – in time and space – of how phase transitions unfold.

Using XPCS, the team was able to examine phase transitions in the material on length scales from the level of individual atoms up to nearly the diameter of a human hair, something not previously possible.

Expecting to find the transformation complete at hundreds of nanoseconds – a nanosecond is a billionth of a second – the team instead discovered that it was only halfway done by that point, and the full process could take tens of milliseconds, nearly one hundred thousand times longer. “This is analogous to Google Maps saying that you have reached your destination, when in fact you are only halfway there, and the other half is going to take a lot longer than you previously thought,” said Venkatraman Gopalan, co-author and professor at The Pennsylvania State University.

New details also emerged about how the phases and their boundaries form, grow and interact with each other and are associated with the heterogeneity of the transformation. These heterogeneous processes, commented Gopalan, are like unanticipated traffic jams that slow you down and then take time to clear.

Animation illustrating phase transformation

“Altogether, our findings show how these materials systems are complex and involve correlated motion at the boundaries of different phases on multiple time- and length-scales,” Lindenberg said. “Through this approach, we could visualize and uncover details that we were blind to when using conventional approaches.”

The successful use of XPCS opens the door for investigations into similar processes for other materials systems and devices. “This advanced technique offers a way to probe and visualize heterogeneous and dynamical processes,” Lindenberg said. “We can apply the knowledge we gained to technologically relevant goals like designing materials for faster switching devices or information storage technologies that operate with lower energy costs.”

The DOE Office of Science (Basic Energy Sciences Materials Sciences and Engineering Division) supported this research. LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

Citation: Anudeep Mangu et al., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 8 January 2025 (10.1073/pnas.2407772122)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact SLAC Strategic Communications & External Affairs at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.