A fast, accurate system for quickly solving stubborn RNA structures from pond scum, the SARS-CoV-2 virus and more

SLAC and Stanford scientists used it to zoom in on an iconic RNA catalyst and a piece of viral RNA that’s a potential target for COVID-19 treatments.

By Glennda Chui

The single-stranded genetic material RNA is best known for guiding the assembly of proteins in our cells and carrying the genetic code for viruses like SARS-CoV-2 and HIV. But 40 years ago, scientists discovered another hidden talent: It can catalyze chemical reactions in the cell, including snipping and joining RNA strands. This gave new momentum to the idea that RNA was the driving force behind the evolution of large molecules that ultimately led to life.

While scientists have learned a lot since then, they haven’t been able to get 3D images of naked RNA molecules in high enough resolution to see all the pockets and folds and other structures that are key to understanding how they function. The molecules are like fidgety kids with floppy arms that won’t hold still for a photo unless they’re part of a larger molecular complex that pins them in place.

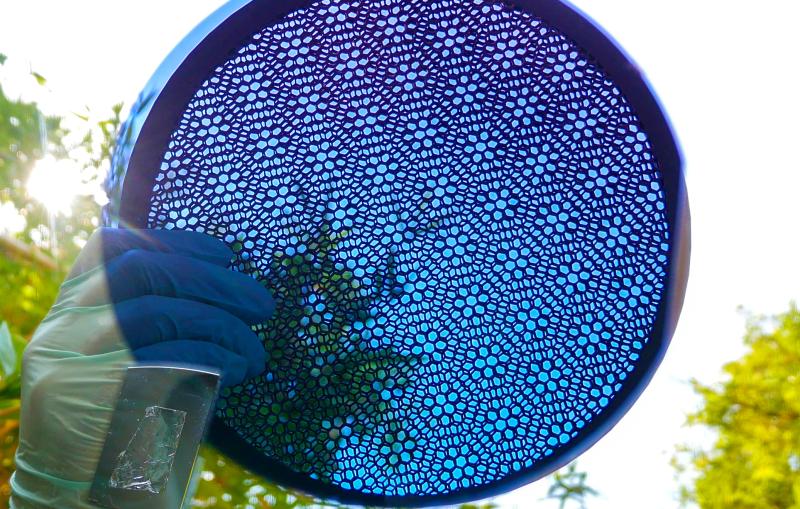

A new system developed at Stanford University and the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory solves that problem. It combines computer software and cryogenic electron microscopy, or cryo-EM, to determine the 3D structures of RNA-only molecules with unprecedented speed, accuracy and resolution.

In two new studies, the research team led by SLAC/Stanford Professor Wah Chiu and Stanford Professor Rhiju Das push the resolution of the technique to as high as 3.1 angstroms – just shy of the point where individual atoms become visible – and apply it to two RNA structures that are of profound interest to scientists.

The first study, published in Nature today, reveals the first full-length, near-atomic structure of a catalytic RNA, or ribozyme, from a one-celled creature called Tetrahymena that lives in pond scum. It was the first ribozyme ever discovered and has served as a sort of lab rat for studying ribozymes ever since.

The second, published in Nature Structural and Molecular Biology, reveals tiny pockets in a bit of RNA from SARS-CoV-2 called the frameshift stimulation element, or FSE. It subtly tricks infected cells into making alternative sets of viral proteins, and plays such an important role in the virus’s ability to replicate that it remains the same even when other parts of the virus mutate to create new variants. This makes it a good potential target for drugs to treat COVID-19, its variants and maybe even other coronaviruses, and a number of research groups have been exploring that possibility.

The FSE study was carried out in 2020, at a time when SLAC and Stanford were shut down due to the pandemic and only essential work related to the coronavirus response was allowed.

Guided by insights from their 3D structure of FSE, Das’s team and collaborators in Professor Jeff Glenn’s lab at Stanford engineered DNA molecules that pair up with a strategic region of the FSE and disrupt its structure.

While researchers are very far from demonstrating that such a molecule could thwart viral infection in humans, the study does identify a potential path for eventually developing a treatment, the scientists said.

“We don’t know what the next pandemic virus will be,” Das said, “but we’re pretty confident it will be a single-strand RNA virus transmitted from animals to humans, and it will likely have a few bits of RNA that resist mutation. With this accelerated system we’ve developed, it now seems feasible to study viruses found in humans or animals, look for those conserved bits, quickly determine their 3D RNA structures and develop antivirals against them.”

A passionate pursuit of RNA

The two scientists started collaborating in 2017 after Das heard Chiu give a talk on using cryo-EM to solve the structure of RNA molecules.

“It blew me away,” Das recalled. “I had fallen in love with RNA in 2001. I thought it was the most important molecule of life. The first RNA molecule I looked at was this Tetrahymena ribozyme. Many, many people had worked on it – it was a bit of a cult molecule – and I spent five years of my PhD work trying to understand how it folds. So after hearing Wah’s talk I suggested that we work together to determine its structure.”

As far as scientists can tell, the ribozyme has no biological function in Tetrahymena, Das said: “It’s an inconsequential molecule in what some might consider an inconsequential organism.” But 40 years ago, when Thomas Cech discovered that this tiny piece of RNA could cut itself out of a Tetrahymena RNA strand, paste the two loose ends together and float away, “it was this magical thing that no one expected an RNA strand to do on its own,” Das said. “They immediately realized that this piece of RNA must be a little multistep machine – a catalyst.” Cech shared the 1989 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery.

Chiu had begun a similar love affair with cryo-EM as a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley in the 1970s. Now the founding co-director of the Stanford-SLAC Cryo-EM Facilities, where the imaging for these studies was done, he has devoted his career to honing the technique and using it to examine cells and the molecular machines inside them in finer and finer detail – not just to see smaller things but to understand how they function and interact with each other.

“It’s been a dream of mine to use cryo-EM to study RNA in all its forms,” Chiu said. “I consider getting these RNA structures one of my top accomplishments. If we can do this with one molecule, in theory we can do it with many others.”

Developing an RNA pipeline

Das and Chiu’s work builds on Ribosolve, a pipeline their groups developed in the two years prior to the pandemic that allows them to quickly solve the structures of RNAs one right after another, more reliably and in much more detail than before. It combines computational tools developed by Stanford PhD student Kalli Kappel with chemical mapping tools from the Das lab and cryo-EM imaging advances from postdoctoral researchers Kaiming Zhang and Zhaoming Su.

In a paper in Nature Methods last year, the team reported using the new approach to determine the 3D structures of the Tetrahymena ribozyme and 10 other RNA molecules with better than 10 angstrom resolution.

“Each of these 11 new structures turned out to provide biological or biochemical insights,” wrote Jane S. Richardson, a professor of biochemistry at Duke University, in a commentary that accompanied the report. She called the approach a “groundbreaking new method” that produces fast and reliable structures of RNA-only molecules that were not considered feasible before, and added that increasing the resolution to 2-4 angstroms would be a desirable demonstration of its usefulness for both RNA and proteins.

In their new Nature paper, the team reports that it has now achieved that higher resolution for the Tetrahymena ribozyme and is hoping to push toward it for FSE, with the ultimate goal of producing atomic-resolution structures for these and potentially thousands of other RNAs.

“I do think the Ribosolve pipeline has the potential to transform our understanding of these molecules, and maybe our ability to develop medicines, too,” Das said. “This couldn’t have happened anywhere else. Having access to world-class cryo-EM instruments was key, along with meeting someone like Wah who shared our intuition that this could be important.”

Citations:

Zhaoming Su et al., Nature, 11 August 2021 (10.1038/s41586-021-03803-w)

Kaiming Zhang et al., Nature Structural and Molecular Biology, 23 August 2021 (10.1038/s41594-021-00653-y)

Work on the Tetrahymena ribozyme was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

Researchers from the University of North Carolina and Harvard University also contributed to the work on the SARS-CoV-2 FSE. It was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the DOE Office of Science through the National Virtual Biotechnology Laboratory, a consortium of DOE national laboratories focused on response to COVID-19, with funding provided by the Coronavirus CARES Act.

Editor's note: This article was updated Aug. 23 to include links to the paper in Nature Structural and Molecular Biology.

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.