First detailed electronic study of new nickelate superconductor

Discovered at SLAC and Stanford, this new class of unconventional superconductors is starting to give up its secrets – including a surprising 3D metallic state.

By Glennda Chui

The discovery last year of the first nickel oxide material that shows clear signs of superconductivity set off a race by scientists around the world to find out more. The crystal structure of the material is similar to copper oxides, or cuprates, which hold the world record for conducting electricity with no loss at relatively high temperatures and normal pressures. But do its electrons behave in the same way?

The answers could help advance the synthesis of new unconventional superconductors and their use for power transmission, transportation and other applications, and also shed light on how the cuprates operate – which is still a mystery after more than 30 years of research.

In a paper published today in Nature Materials, a team led by scientists at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University report the first detailed investigation of the electronic structure of superconducting nickel oxides, or nickelates. The scientists used two techniques, resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS) and X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), to get the first complete picture of the nickelates’ electronic structure – basically the arrangement and behavior of their electrons, which determine a material’s properties.

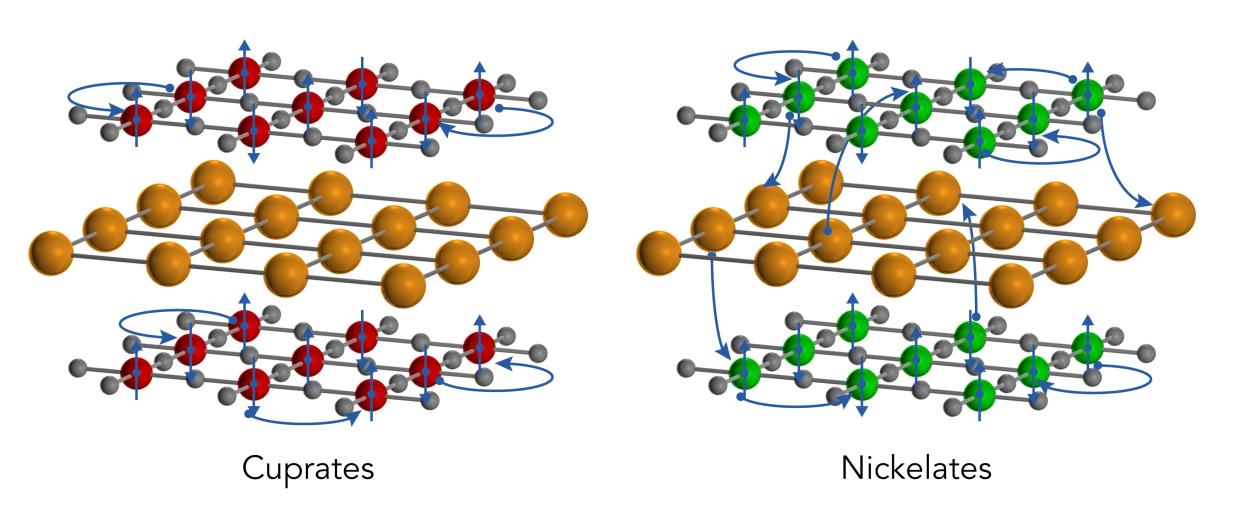

Both cuprates and nickelates come in thin, two-dimensional sheets that are layered with other elements, such as rare-earth ions. These thin sheets become superconducting when they’re cooled below a certain temperature and the density of their free-flowing electrons is adjusted in a process known as “doping.”

Cuprates are insulators in their pre-doped “ground” states, meaning that their electrons are not mobile. After doping the electrons can move freely but they are mostly confined to the cuprate layers, rarely traveling through the intervening rare-earth layers to reach their cuprate neighbors.

But in the nickelates, the team discovered, this is not the case. The undoped compound is a metal with freely flowing electrons. Furthermore, the intervening layers actually contribute electrons to the nickelate sheets, creating a three-dimensional metallic state that is quite different from what’s seen in the cuprates.

This is an entirely new type of ground state for transition metal oxides such as cuprates and nickelates, the researchers said. It opens new directions for experiments and theoretical studies of how superconductivity arises and how it can be optimized in this system and possibly in other compounds.

The study was funded by the DOE Office of Science through the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES) at SLAC. The lead authors of the study were SIMES researchers Matthias Hepting (now at Max Planck Institute in Stuttgart, Germany), Wei-Sheng Lee and Chunjing Jia. The team also included SIMES researcher Danfeng Li, who led the experiments that discovered the new superconducting nickelates, as well as theorists at SIMES and at Leiden University in The Netherlands.

XAS and RIXS measurements were carried out at the Swiss Light Source in Switzerland, the Diamond Light Source in the United Kingdom, NSRRC in Taiwan and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory’s Advanced Light Source, which is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

Citation: M. Hepting et al., Nature Materials, 20 January 2020 (s41563-019-0585-z)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.