First report of superconductivity in a nickel oxide material

Made with ‘Jenga chemistry,’ the discovery could help crack the mystery of how high-temperature superconductors work.

By Glennda Chui

Menlo Park, Calif. — Scientists at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University have made the first nickel oxide material that shows clear signs of superconductivity – the ability to transmit electrical current with no loss.

Also known as a nickelate, it’s the first in a potential new family of unconventional superconductors that’s very similar to the copper oxides, or cuprates, whose discovery in 1986 raised hopes that superconductors could someday operate at close to room temperature and revolutionize electronic devices, power transmission and other technologies. Those similarities have scientists wondering if nickelates could also superconduct at relatively high temperatures.

At the same time, the new material seems different from the cuprates in fundamental ways – for instance, it may not contain a type of magnetism that all the superconducting cuprates have – and this could overturn leading theories of how these unconventional superconductors work. After more than three decades of research, no one has pinned that down.

The experiments were led by Danfeng Li, a postdoctoral researcher with the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES) at SLAC, and described today in Nature.

“This is a very important discovery that requires us to rethink the details of the electronic structure and possible mechanisms of superconductivity in these materials,” said George Sawatzky, a professor of physics and chemistry at the University of British Columbia who was not involved in the study but wrote a commentary that accompanied the paper in Nature. “This is going to cause an awful lot of people to jump into investigating this new class of materials, and all sorts of experimental and theoretical work will be done.”

A difficult path

Ever since the cuprate superconductors were discovered, scientists have dreamed of making similar oxide materials based on nickel, which is right next to copper on the periodic table of the elements.

But making nickelates with an atomic structure that’s conducive to superconductivity turned out to be unexpectedly hard.

“As far as we know, the nickelate we were trying to make is not stable at the very high temperatures – about 600 degrees Celsius – where these materials are normally grown,” Li said. “So we needed to start out with something we can stably grow at high temperatures and then transform it at lower temperatures into the form we wanted.”

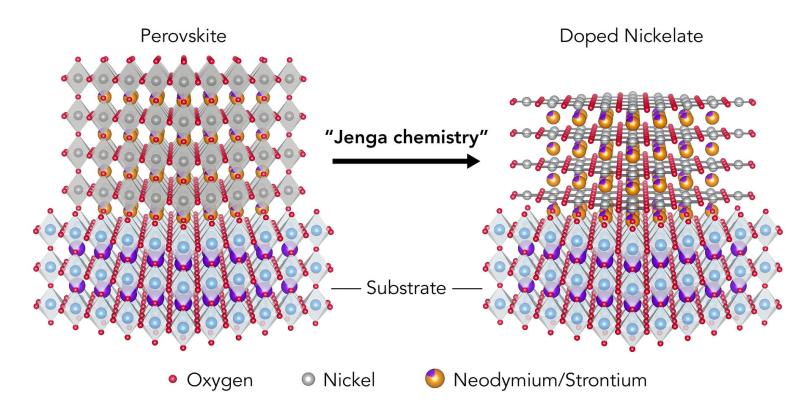

He started with a perovskite – a material defined by its unique, double-pyramid atomic structure – that contained neodymium, nickel and oxygen. Then he doped the perovskite by adding strontium; this is a common process that adds chemicals to a material to make more of its electrons flow freely.

This stole electrons away from nickel atoms, leaving vacant “holes,” and the nickel atoms were not happy about it, Li said. The material was now unstable, making the next step – growing a thin film of it on a surface – really challenging; it took him half a year to get it to work.

‘Jenga chemistry’

Once that was done, Li cut the film into tiny pieces, loosely wrapped it in aluminum foil and sealed it in a test tube with a chemical that neatly snatched away a layer of its oxygen atoms – much like removing a stick from a wobbly tower of Jenga blocks. This flipped the film into an entirely new atomic structure – a strontium-doped nickelate.

Jenga Chemistry

“Each of these steps had been demonstrated before,” Li said, “but not in this combination.”

He remembers the exact moment in the laboratory, around 2 a.m., when tests indicated that the doped nickelate might be superconducting. Li was so excited that he stayed up all night, and in the morning co-opted the regular meeting of his research group to show them what he’d found. Soon, many of the group members joined him in a round-the-clock effort to improve and study this material.

Further testing would reveal that the nickelate was indeed superconducting in a temperature range from 9-15 kelvins – incredibly cold, but a first start, with possibilities of higher temperatures ahead.

More work ahead

Research on the new material is in a “very, very early stage, and there’s a lot of work ahead,” cautioned Harold Hwang, a SIMES investigator, professor at SLAC and Stanford and senior author of the report. “We have just seen the first basic experiments, and now we need to do the whole battery of investigations that are still going on with cuprates.”

Among other things, he said, scientists will want to dope the nickelate material in various ways to see how this affects its superconductivity across a range of temperatures, and determine whether other nickelates can become superconducting. Other studies will explore the material’s magnetic structure and its relationship to superconductivity.

SIMES researchers from the Stanford departments of Physics, Applied Physics and Materials Science and Engineering also contributed to the study, which was funded by the DOE Office of Science and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation’s Emergent Phenomena in Quantum Systems Initiative.

Citation: D. Li et al., Nature, 28 August 2019 (10.1038/s41586-019-1496-5)

Press Office Contact: Glennda Chui, glennda@slac.stanford.edu, (650) 926-4897.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.