Study shows single atoms can make more efficient catalysts

Detailed observations of iridium atoms at work could help make catalysts that drive chemical reactions smaller, cheaper and more efficient.

By Glennda Chui

Catalysts are chemical matchmakers: They bring other chemicals close together, increasing the chance that they’ll react with each other and produce something people want, like fuel or fertilizer.

Since some of the best catalyst materials are also quite expensive, like the platinum in a car’s catalytic converter, scientists have been looking for ways to shrink the amount they have to use.

Now scientists have their first direct, detailed look at how a single atom catalyzes a chemical reaction. The reaction is the same one that strips poisonous carbon monoxide out of car exhaust, and individual atoms of iridium did the job up to 25 times more efficiently than the iridium nanoparticles containing 50 to 100 atoms that are used today.

The research team, led by Ayman M. Karim of Virginia Tech, reported the results in Nature Catalysis.

“These single-atom catalysts are very much a hot topic right now,” said Simon R. Bare, a co-author of the study and distinguished staff scientist at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, where key parts of the work took place. “This gives us a new lens to look at reactions through, and new insights into how they work.”

Karim added, “To our knowledge, this is the first paper to identify the chemical environment that makes a single atom catalytically active, directly determine how active it is compared to a nanoparticle, and show that there are very fundamental differences – entirely different mechanisms – in the way they react.”

Is smaller really better?

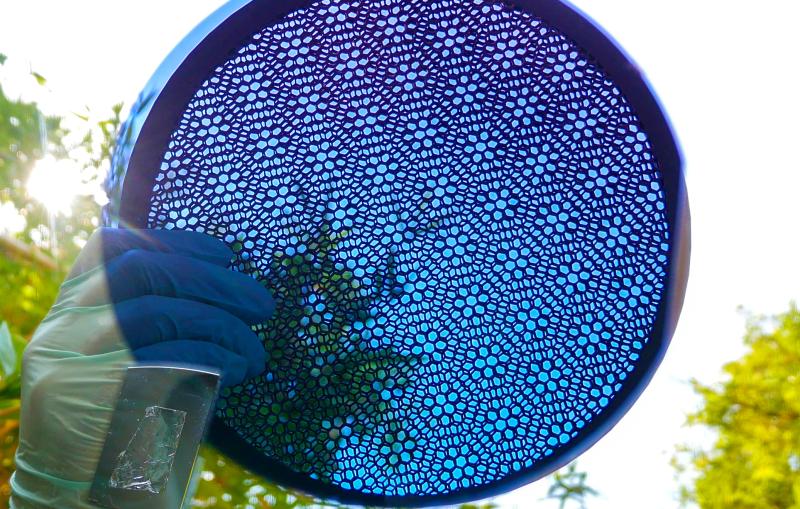

Catalysts are the backbone of the chemical industry and essential to oil refining, where they help break crude oil into gasoline and other products. Today’s catalysts often come in the form of nanoparticles attached to a surface that’s porous like a sponge – so full of tiny holes that a single gram of it, unfolded, might cover a basketball court. This creates an enormous area where millions of reactions can take place at once. When gas or liquid flows over and through the spongy surface, chemicals attach to the nanoparticles, react with each other and float away. Each catalyst is designed to promote one specific reaction over and over again.

But catalytic reactions take place only on the surfaces of nanoparticles, Bare said, “and even though they are very small particles, the expensive metal on the inside of the nanoparticle is wasted.”

Individual atoms, on the other hand, could offer the ultimate in efficiency. Each and every atom could act as a catalyst, grabbing chemical reactants and holding them close together until they bond. You could fit a lot more of them in a given space, and not a speck of precious metal would go to waste.

Single atoms have another advantage: Unlike clusters of atoms, which are bound to each other, single atoms are attached only to the surface, so they have more potential binding sites available to perform chemical tricks – which in this case came in very handy.

Research on single-atom catalysts has exploded over the past few years, Karim said, but until now no one has been able to study how they function in enough detail to see all the fleeting intermediate steps along the way.

Grabbing some help

To get more information, the team looked at a simple reaction where single atoms of iridium split oxygen molecules in two, and the oxygen atoms then react with carbon monoxide to create carbon dioxide.

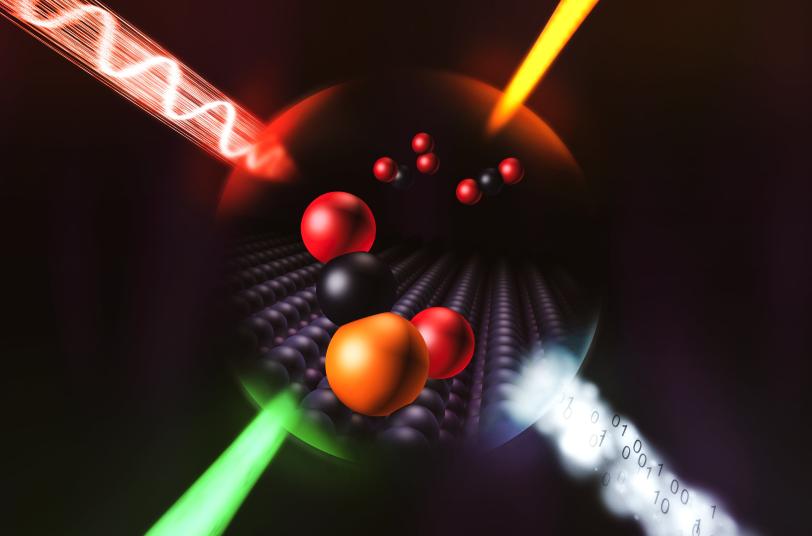

They used four approaches – infrared spectroscopy, electron microscopy, theoretical calculations and X-ray spectroscopy with beams from SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) – to attack the problem from different angles, and this was crucial for getting a complete picture.

“It’s never just one thing that gives you the full answer,” Bare said. “It’s always multiple pieces of the jigsaw puzzle coming together.”

The team discovered that each iridium atom does, in fact, perform a chemical trick that enhances its performance. It grabs a single carbon monoxide molecule out of the passing flow of gas and holds onto it, like a person tucking a package under their arm. The formation of this bond triggers tiny shifts in the configuration of the iridium atom’s electrons that help it split oxygen, so it can react with the remaining carbon monoxide gas and convert it to carbon dioxide much more efficiently.

More questions lie ahead: Will this same mechanism work in other catalytic reactions, allowing them to run more efficiently or at lower temperatures? How do the nature of the single-atom catalyst and the surface it sits on affect its binding with carbon monoxide and the way the reaction proceeds?

The team plans to return to SSRL in January to continue the work.

SSRL is a DOE Office of Science user facility. Scientists from Stanford University, SUNCAT Center for Interface Science and Catalysis and DOE’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory also contributed to the study, which was funded by the Army Research Office.

Citation: Lu et al., Nature Catalysis, 31 December 2018 (10.1038/s41929-018-0192-4)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.