To Get More Oomph from an Electron Gun, Tip it With Diamondoids

Scientists Discover that a Single Layer of Tiny Diamonds Increases Electron Emission 13,000-fold

They sound like futuristic weapons, but electron guns are actually workhorse tools for research and industry: They emit streams of electrons for electron microscopes, semiconductor patterning equipment and particle accelerators, to name a few important uses.

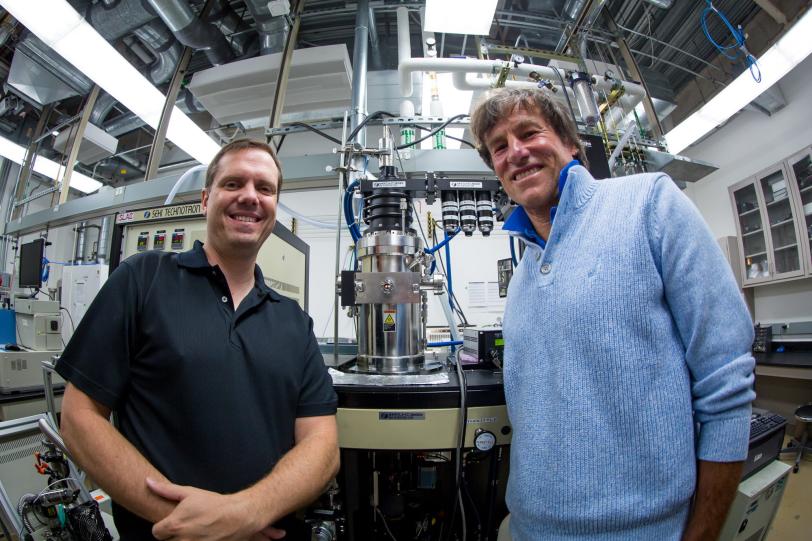

Now scientists at Stanford University and the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have figured out how to increase these electron flows 13,000-fold by applying a single layer of diamondoids – tiny, perfect diamond cages – to an electron gun’s sharp gold tip.

The results, published today in Nature Nanotechnology, suggest a whole new approach for increasing the power of these devices. They also provide an avenue for designing other types of electron emitters with atom-by-atom precision, said Nick Melosh, an associate professor at SLAC and Stanford who led the study.

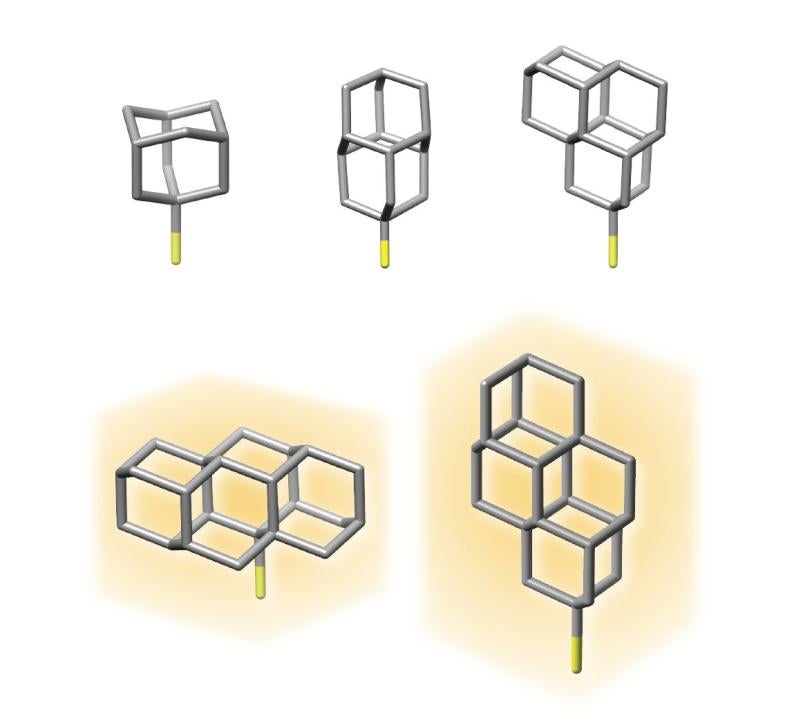

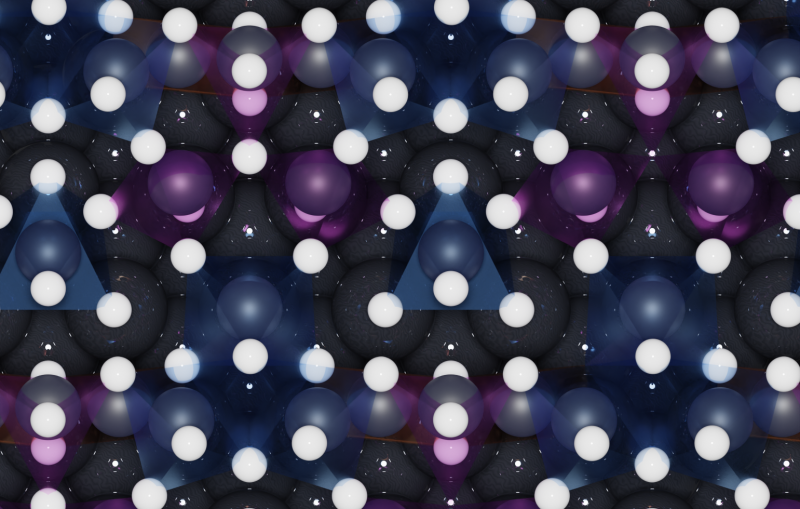

Diamondoids are interlocking cages made of carbon and hydrogen atoms. They’re the smallest possible bits of diamond, each weighing less than a billionth of a billionth of a carat. That small size, along with their rigid, sturdy structure and high chemical purity, give them useful properties that larger diamonds lack.

SLAC and Stanford have become one of the world’s leading centers for diamondoid research. Studies are carried out through SIMES, the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences, and a lab at SLAC is devoted to extracting diamondoids from petroleum.

In 2007, a team led by many of the same SIMES researchers showed that a single layer of diamondoids on a metal surface could emit and focus electrons into a tiny beam with a very narrow range of energies.

The new study looked at whether a diamondoid coating could also improve emissions from electron guns.

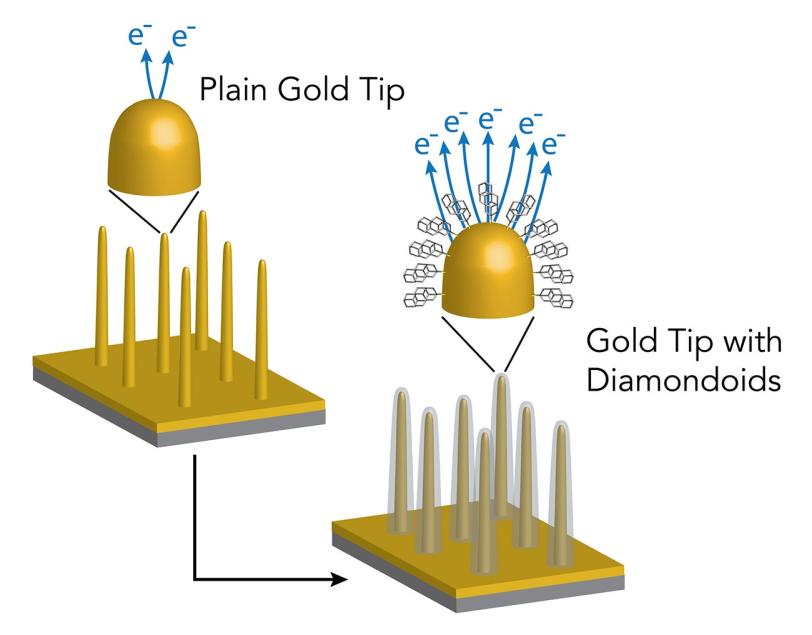

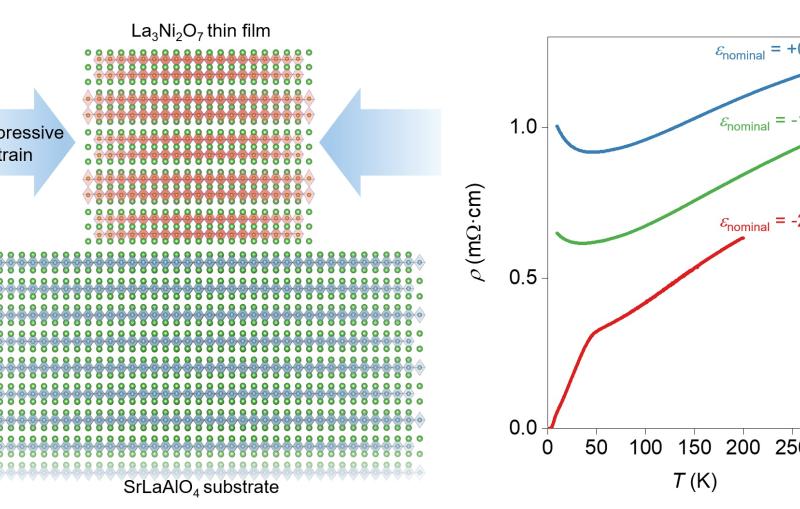

One way to increase the power of an electron gun is to make the tip really sharp, which makes it easier to get the electrons out, Melosh said. But these sharp tips are unstable; even tiny irregularities can affect their performance. Researchers have tried to get around this by coating the tips with chemicals that boost electron emission, but this can be problematic because some of the most effective ones burst into flames when exposed to air.

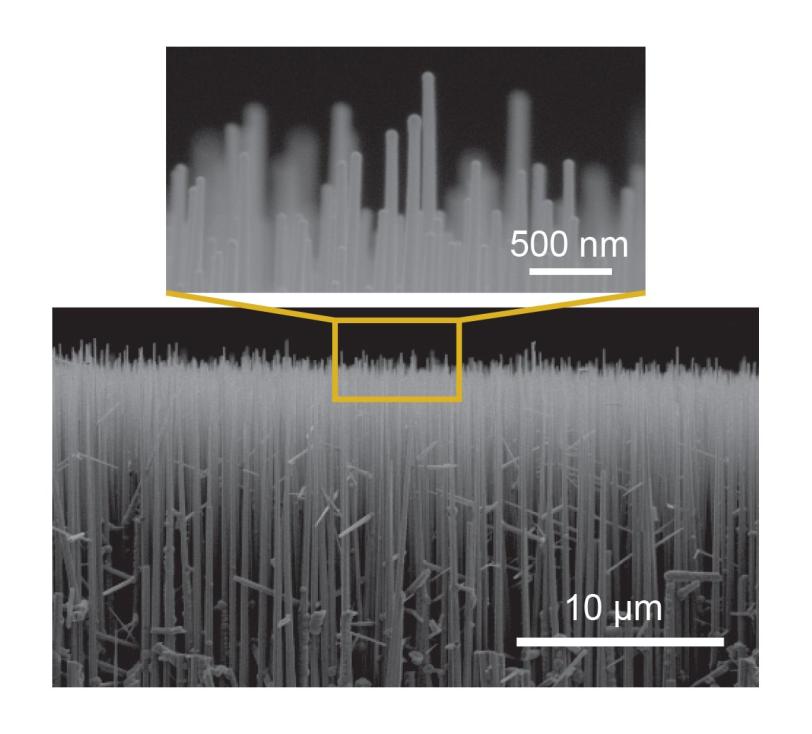

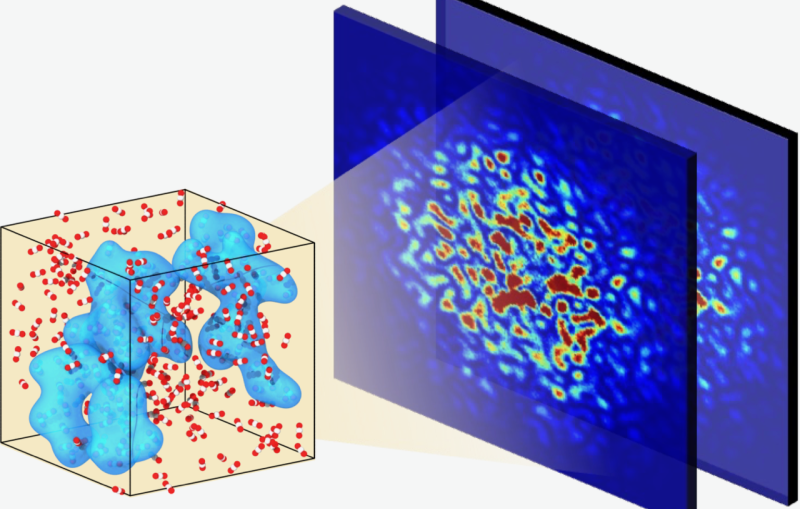

For this study, the scientists used tiny nanopillars of germanium wire as stand-ins for electron gun tips. They coated the wires with gold and then with diamondoids of various sizes.

When the scientists applied a voltage to the nanowires to stimulate the release of electrons from the tips, they found they got the best results from tips coated with diamondoids that consist of four “cages.” These released a whopping 13,000 times more electrons than bare gold tips.

Further tests and computer simulations suggest that the increase was not due to changes in the shape of the tip or in the underlying gold surface. Instead, it looks like some of the diamondoid molecules in the tip lost a single electron – it’s not clear exactly how. This created a positive charge that attracted electrons from the underlying surface and made it easier for them to flow out of the tip, Melosh said.

“Most other molecules would not be stable if you removed an electron; they’d fall apart,” he said. “But the cage-like nature of the diamondoid makes it unusually stable, and that’s why this process works. Now that we understand what’s going on, we may be able to use that knowledge to engineer other materials that are really good at emitting electrons.”

In addition to SLAC and Stanford, the research team included scientists from Justus-Liebig University, Giessen in Germany and Kiev Polytechnic Institute in Ukraine. The research was funded by the DOE Office of Science.

Citation: K. Narasimha et al, Nature Nanotechnology, 7 December 2015 (10.1038/nnano.2015.277)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.