X-ray Laser Reveals How Bacterial Protein Morphs in Response to Light

A Series of Super-Sharp Snapshots Demonstrates a New Tool for Tracking Life's Chemistry

Human biology is a massive collection of chemical reactions, from the intricate signaling network that powers our brain activity to the body’s immune response to viruses and the way our eyes adjust to sunlight. All involve proteins, known as the molecules of life; and scientists have been steadily moving toward their ultimate goal of following these life-essential reactions step by step in real time, at the scale of atoms and electrons.

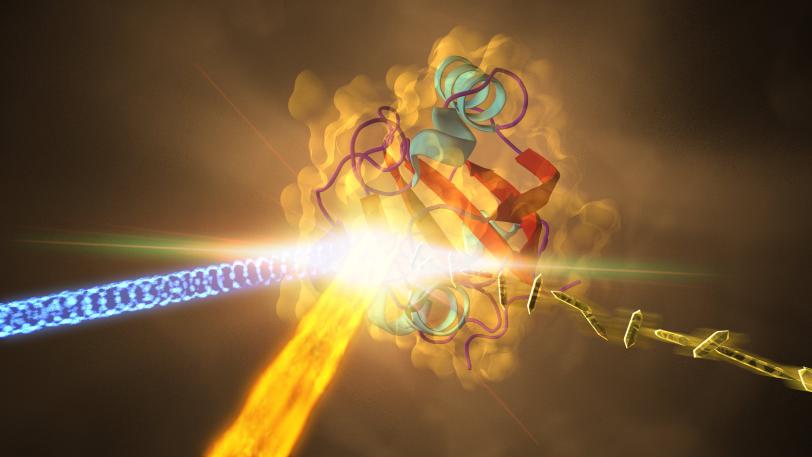

Now, researchers have captured the highest-resolution snapshots ever taken with an X-ray laser that show changes in a protein’s structure over time, revealing how a key protein in a photosynthetic bacterium changes shape when hit by light. They achieved a resolution of 1.6 angstroms, equivalent to the radius of a single tin atom.

"These results establish that we can use this same method with all kinds of biological molecules, including medically and pharmaceutically important proteins," said Marius Schmidt, a biophysicist at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee who led the experiment at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. There is particular interest in exploring the fastest steps of chemical reactions driven by enzymes -- proteins that act as the body's natural catalysts, he said: "We are on the verge of opening up a whole new unexplored territory in biology, where we can study small but important reactions at ultrafast timescales.”

The results, detailed in a report published online Dec. 4 in Science, have exciting implications for research on some of the most pressing challenges in life sciences, which include understanding biology at its smallest scale and making movies that show biological molecules in motion.

A New Way to Study Shape-shifting Proteins

The experiment took place at SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), a DOE Office of Science User Facility. LCLS’s X-ray laser pulses, which are about a billion times brighter than X-rays from synchrotrons, allowed researchers to see atomic-scale details of how the bacterial protein changes within millionths of a second after it’s exposed to light.

"This experiment marks the first time LCLS has been used to directly observe a protein’s structural change as it happens. It opens the door to reaching even faster time scales," said Sébastien Boutet, a SLAC staff scientist who oversees the experimental station used in the study. LCLS's pulses, measured in quadrillionths of a second, work like a super-speed camera to record ultrafast changes, and snapshots taken at different points in time can be compiled into detailed movies.

The protein the researchers studied, found in purple bacteria and known as PYP for "photoactive yellow protein," functions much like a bacterial eye in sensing blue light. The mechanism is very similar to that of other receptors in biology, including receptors in the human eye. "Though the chemicals are different, it's the same kind of reaction," said Schmidt, who has studied PYP since 2001. Proving the technique works with a well-studied protein like PYP sets the stage to study more complex and biologically important molecules at LCLS, he said.

Chemistry on the Fly

In the LCLS experiment, researchers prepared crystallized samples of the protein, and exposed the crystals, each about 2 millionths of a meter long, to blue laser light before jetting them into the LCLS X-ray beam.

The X-rays produced patterns as they struck the crystals, which were used to reconstruct the 3-D structures of the proteins. Researchers compared the structures of the proteins that had been exposed to light to those that had not to identify light-induced structural changes.

"In the future we plan to study all sorts of enzymes and other proteins using this same technique," Schmidt said. "This study shows that the molecular details of life’s chemistry can be followed using X-ray laser crystallography, which puts some of biology’s most sought-after goals within reach.”

Researchers from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and SLAC were joined by researchers from Arizona State University; Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory; University of Hamburg and DESY in Hamburg, Germany; State University of New York, Buffalo; University of Chicago; and Imperial College in London. The work was supported by the National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Health and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

Citation: Jason Tenboer, Shibom Basu, et al., Science, 5 December 2014 (10.1126/science.1259357).

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.