Study at SLAC Explains Atomic Action in High-Temperature Superconductors

Results are First to Suggest How to Engineer Even Warmer Superconductors with Atom-by-Atom Control

Menlo Park, Calif. — A study at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory suggests for the first time how scientists might deliberately engineer superconductors that work at higher temperatures.

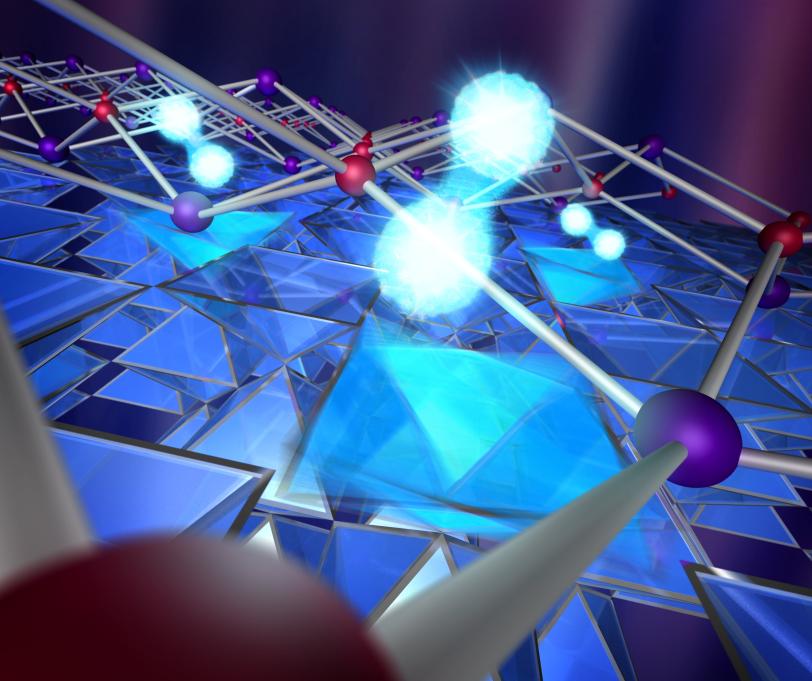

In their report, a team led by SLAC and Stanford University researchers explains why a thin layer of iron selenide superconducts -- carries electricity with 100 percent efficiency -- at much higher temperatures when placed atop another material, which is called STO for its main ingredients strontium, titanium and oxygen.

These findings, described today in the journal Nature, open a new chapter in the 30-year quest to develop superconductors that operate at room temperature, which could revolutionize society by making virtually everything that runs on electricity much more efficient. Although today’s high-temperature superconductors operate at much warmer temperatures than conventional superconductors do, they still work only when chilled to minus 135 degrees Celsius or below.

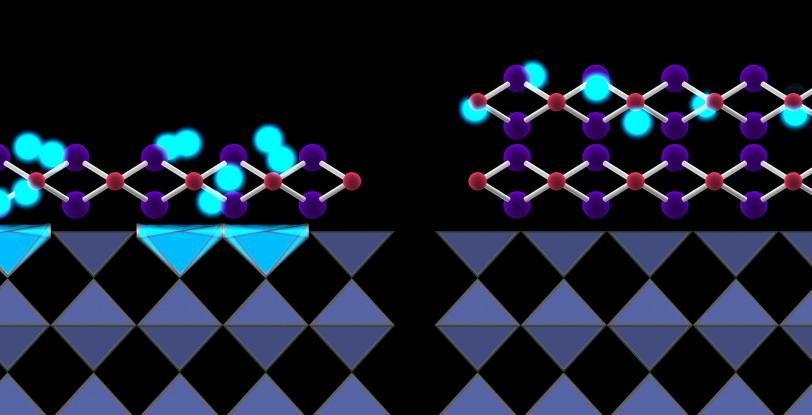

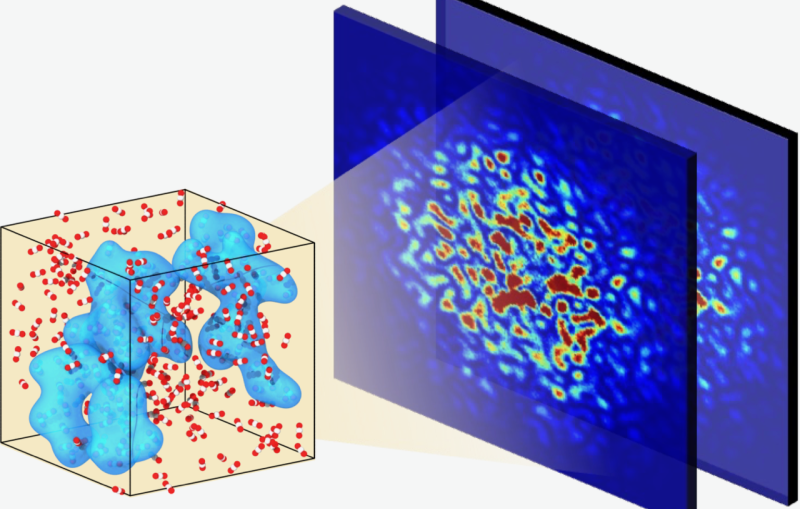

In the new study, the scientists concluded that natural trillion-times-per-second vibrations in the STO travel up into the iron selenide film in distinct packets, like volleys of water droplets shaken off by a wet dog. These vibrations give electrons the energy they need to pair up and superconduct at higher temperatures than they would on their own.

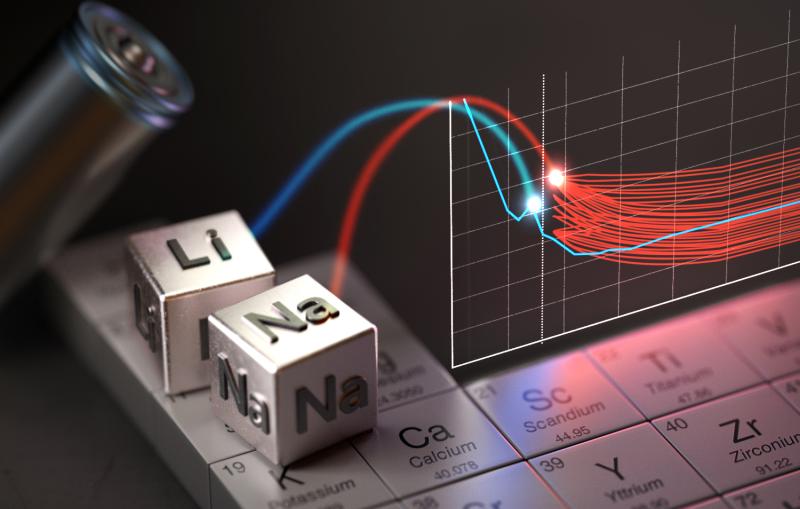

“Our simulations indicate that this approach – using natural vibrations in one material to boost superconductivity in another – could be used to raise the operating temperature of iron-based superconductors by at least 50 percent,” said Zhi-Xun Shen, a professor at SLAC and Stanford University and senior author of the study.

While that’s still nowhere close to room temperature, he added, “We now have the first example of a mechanism that could be used to engineer high-temperature superconductors with atom-by-atom control and make them better.”

Spying on Electrons

The study probed a happy combination of materials developed two years ago by scientists in China. They discovered that when a single layer of iron selenide film is placed atop STO, its maximum superconducting temperature shoots up from 8 degrees to nearly 77 degrees above absolute zero (minus 196 degrees Celsius).

While this was a huge and welcome leap, it would be hard to build on this advance without understanding what, exactly, was going on.

In the new study, SLAC Staff Scientist Rob Moore and Stanford graduate student J.J. Lee and postdoctoral researcher Felix Schmitt built a system for growing iron selenide films just one layer thick on a base of STO.

The team examined the combined material at SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, a DOE Office of Science User Facility. They used an exquisitely sensitive technique called ARPES to measure the energies and momenta of electrons ejected from samples hit with X-ray light. This tells scientists how the electrons inside the sample are behaving; in superconductors they pair up to conduct electricity without resistance. The researchers also got help from theorists who did simulations to help explain what they were seeing.

A Promising New Direction

“This is a very impressive experiment, one that would have been very difficult to impossible to do anywhere else,” said Andrew Millis, a theoretical condensed matter physicist at Columbia University, who was not involved in the study. “And it’s clearly telling us something important about why putting one thin layer of iron selenide on this substrate, which everyone thought was inert and boring, changes things so dramatically. It opens lots of interesting questions, and it will definitely stimulate a lot of research.”

Scientists still don’t know what holds electron pairs together so they can effortlessly carry current in high-temperature superconductors. With no way to deliberately invent new high-temperature superconductors or improve old ones, progress has been slow.

The new results “point to a new direction that people have not considered before,” Moore said. “They have the potential to really break records in high-temperature superconductivity and give us a new understanding of things we’ve been struggling with for years.”

He added that SLAC is developing a new X-ray beamline at SSRL with a more advanced ARPES system to create and study these and other exotic materials. “This paper predicts a new pathway to engineering superconductivity in these materials,” Moore said, “and we’re building the tools to do just that.”

In addition to researchers from SLAC’s Materials Science Division and from Stanford, scientists from the University of British Columbia, the University of Tennessee, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the University of California, Berkeley contributed to this study. The work was funded by the DOE Office of Science.

Citation: J.J. Lee et al., Nature, 13 November 2014 (10.1038/nature13894)

Press Office Contact: Manuel Gnida, mgnida@slac.stanford.edu, 415-308-7832

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, California, SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.