Study Sheds New Light on Why Batteries Go Bad

A comprehensive look at how tiny particles in a lithium ion battery electrode behave shows that rapid-charging the battery and using it to do high-power, rapidly draining work may not be as damaging as researchers had thought – and that the benefits of slow draining and charging may have been overestimated.

Menlo Park, Calif. — A comprehensive look at how tiny particles in a lithium ion battery electrode behave shows that rapid-charging the battery and using it to do high-power, rapidly draining work may not be as damaging as researchers had thought – and that the benefits of slow draining and charging may have been overestimated.

The results challenge the prevailing view that “supercharging” batteries is always harder on battery electrodes than charging at slower rates, according to researchers from Stanford University and the Stanford Institute for Materials & Energy Sciences (SIMES) at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

They also suggest that scientists may be able to modify electrodes or change the way batteries are charged to promote more uniform charging and discharging and extend battery life.

“The fine detail of what happens in an electrode during charging and discharging is just one of many factors that determine battery life, but it’s one that, until this study, was not adequately understood,” said William Chueh of SIMES, an assistant professor at Stanford’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering and senior author of the study. “We have found a new way to think about battery degradation.”

The results, he said, can be directly applied to many oxide and graphite electrodes used in today’s commercial lithium ion batteries and in about half of those under development.

His team described the study September 14, 2014, in Nature Materials. The team included collaborators from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Sandia National Laboratories, Samsung Advanced Institute of Technology America and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Watching Ions in Battery Slices

One important source of battery wear and tear is the swelling and shrinking of the negative and positive electrodes as they absorb and release ions from the electrolyte during charging and discharging.

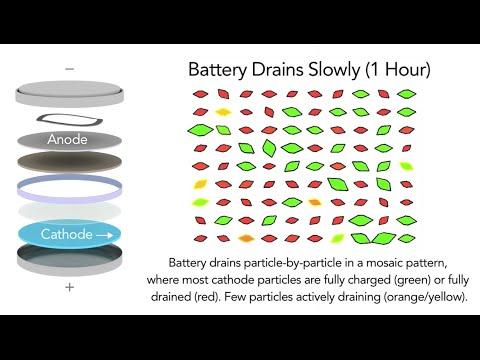

For this study scientists looked at a positive electrode made of billions of nanoparticles of lithium iron phosphate. If most or all of these particles actively participate in charging and discharging, they’ll absorb and release ions more gently and uniformly. But if only a small percentage of particles sop up all the ions, they’re more likely to crack and get ruined, degrading the battery’s performance.

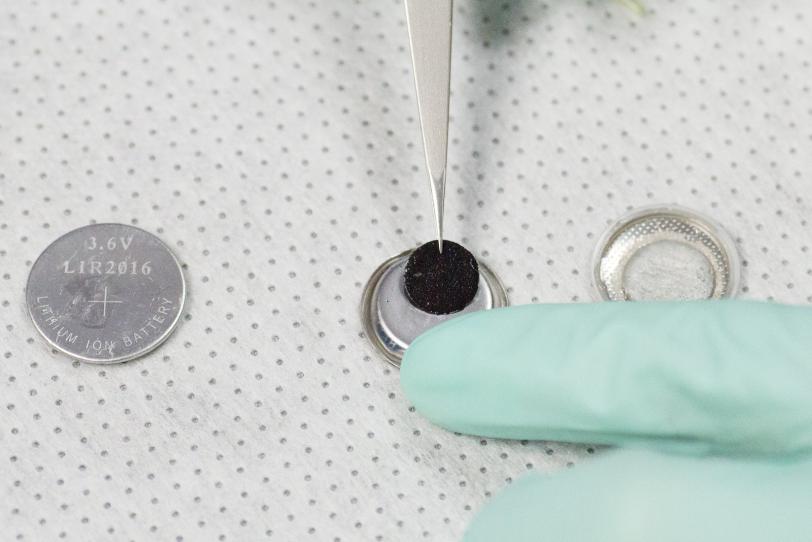

Previous studies produced conflicting views of how the nanoparticles behaved. To probe further, researchers made small coin cell batteries, charged them with different levels of current for various periods of time, quickly took them apart and rinsed the components to stop the charge/discharge process. Then they cut the electrode into extremely thin slices and took them to Berkeley Lab for examination with intense X-rays from the Advanced Light Source synchrotron, a DOE Office of Science User Facility.

New Insights on Faster Discharging

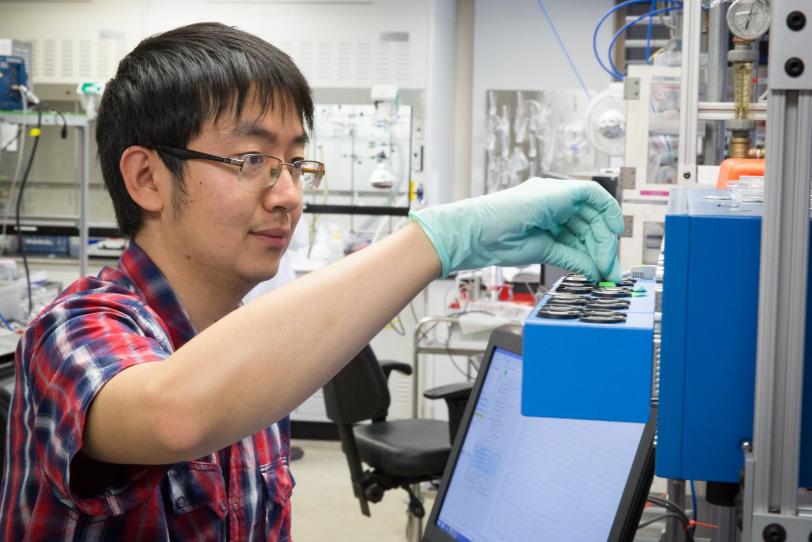

“We were able to look at thousands of electrode nanoparticles at a time and get snapshots of them at different stages during charging and discharging,” said Stanford graduate student Yiyang Li, lead author of the report. “This study is the first to do that comprehensively, under many charging and discharging conditions.”

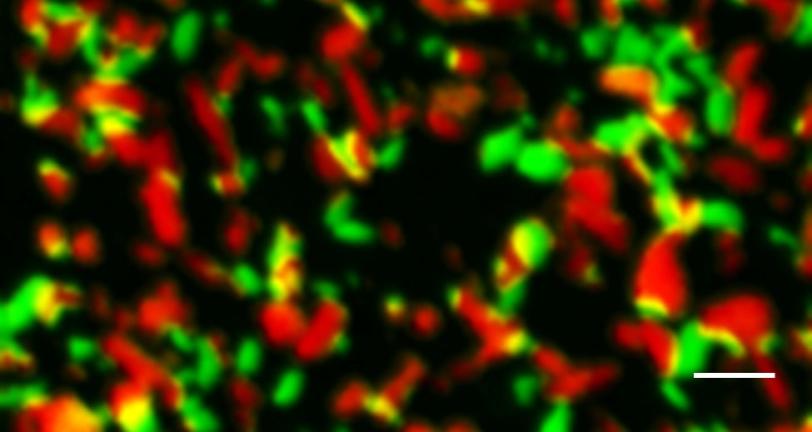

Analyzing the data using a sophisticated model developed at MIT, the researchers discovered that only a small percentage of nanoparticles absorbed and released ions during charging, even when it was done very rapidly. But when the batteries discharged, an interesting thing happened: As the discharge rate increased above a certain threshold, more and more particles started to absorb ions simultaneously, switching to a more uniform and less damaging mode. This suggests that scientists may be able to tweak the electrode material or the process to get faster rates of charging and discharging while maintaining long battery life.

Battery Particle Simulation

The next step, Li said, is to run the battery electrodes through hundreds to thousands of cycles to mimic real-world performance. The scientists also hope to take snapshots of the battery while it’s charging and discharging, rather than stopping the process and taking it apart. This should yield a more realistic view, and can be done at synchrotrons such as ALS or SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, a DOE Office of Science User Facility. Li said the group has also been working with industry to see how these findings might apply in the transportation and consumer electronics sectors.

Research funding came from the Samsung Advanced Institute of Technology Global Research Outreach Program; the School of Engineering and Precourt Institute for Energy at Stanford; the Samsung-MIT Program for Materials Design in Energy Applications; and the U.S. Department of Energy.

Citation: W. Chueh et al., Nature Materials, 14 September 2014 (10.1038/NMAT4084)

Press Office Contact: Manuel Gnida, mgnida@slac.stanford.edu, 415-308-7832

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, California, SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science.

The Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES) is a joint institute of SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University. SIMES studies the nature, properties and synthesis of complex and novel materials in the effort to create clean, renewable energy technologies. For more information, please visit simes.slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.