Catching Chemistry in Motion

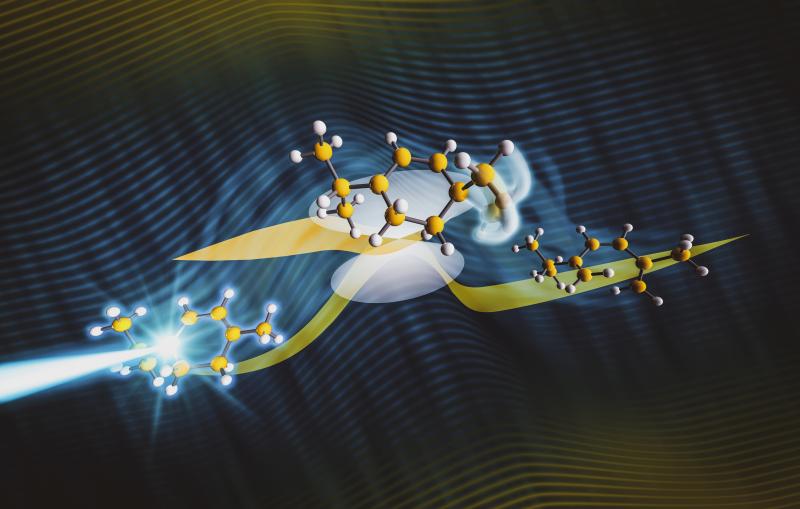

SLAC researchers have developed a laser-timing system that could lead to X-ray snapshots fast enough to reveal the triggers of chemical and material reactions.

Researchers at the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have developed a laser-timing system that could allow scientists to take snapshots of electrons zipping around atoms and molecules. Taking timing to this new extreme of speed and accuracy at the Linac Coherent Light Source X-ray laser, a DOE Office of Science user facility, will make it possible to see the formative stages of chemical reactions.

"Previously, we could see a chemical bond before it's broken and after it's broken," said Ryan Coffee, an LCLS scientist whose team developed this system. "With this tool, we can watch the bond while it is breaking and 'freeze-frame' it."

The success of most LCLS experiments relies on precise timing of the X-ray laser with another laser, a technique known as "pump-probe." Typically, light from an optical laser "pumps" or triggers a specific effect in a sample, and researchers vary the arrival of the X-ray laser pulses, which serve as the "probe" to capture images and other data that allow them to study the effects at different points in time.

Pump-probe experiments at LCLS are used to study a wide range of processes at the atomic or molecular scale, including studies of biological samples and exotic materials like high-temperature superconductors.

But LCLS X-ray pulses are tricky to control. They have inherent jitter that causes them to fluctuate in arrival time, energy, position, duration and the wavelength of their light.

There are several tools and techniques that scientists use to understand and limit the impacts of jitter on experiments, and timing tools counter the arrival-time jitter by offering very precise measurements. These measurements can help scientists to interpret their data by pinpointing the timing of changes they see in samples after they are exposed to the first laser pulse. Some experiments would not be possible without precise timing tools because of the ultrafast scale of the changes they are trying to observe.

Achieving 'Attosecond' Experiments

Timing tools now in place at most LCLS experimental stations can measure the arrival time of the optical and X-ray laser pulses to an accuracy within 10 femtoseconds, or quadrillionths of a second. The new pulse-measuring system, which is highlighted in the July 27 edition of Nature Photonics, builds upon the existing tools and pushes timing to attoseconds, which are quintillionths (billion-billionths) of a second.

Nick Hartmann, an LCLS research associate and doctoral student at the University of Bern in Switzerland who is the lead author of the study detailing the system, said, "An X-ray laser with attosecond timing resolution would open up a new class of experiments on the natural time scale of electron motion."

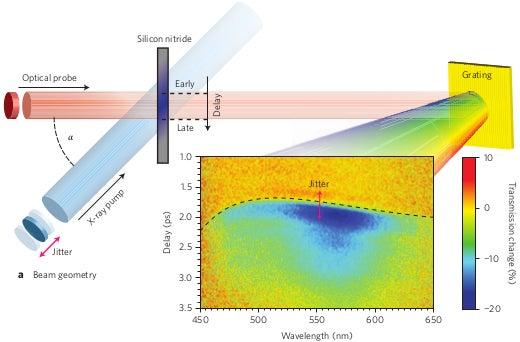

The new system uses a high-resolution spectrograph, a type of camera that records the timing and wavelength of the probe laser pulses. The colorful patterns it displays represent the different wavelengths of light that passed, at slightly different times, through a thin sample of silicon nitride.

This material experiences a cascading reaction in its electrons when it is struck by an X-ray pulse. This effect leaves a brief imprint in the way light passes through the sample, sort of like a temporary interruption of vision following a camera's flash.

This X-ray-caused effect shows up in the way the light from the other laser pulse passes through the silicon nitride – it is seen as a brief dip in the amount of light recorded by the spectrograph, like the after-image of a camera flash. An image-analysis algorithm then precisely calculates, based on the recorded patterns, the relative arrival time of the X-ray pulses.

The new timing system is designed to avoid distortion effects caused by some other timing tools and to work reliably with a variety of focusing and filtering tools. It can provide real-time readouts of laser arrival times and jitter to benefit experiments in progress, and can be added to existing timing setups at LCLS.

Hartmann said additional innovations could expand the applications of the new system: "We are putting the parts together to allow attosecond experiments at LCLS and other X-ray lasers like it."

Citation: N. Hartmann, W. Helml et al. Nature Photonics, 27 July 2014 (10.1038/NPHOTON.2014.164)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.