Curiosity Created the Chemist

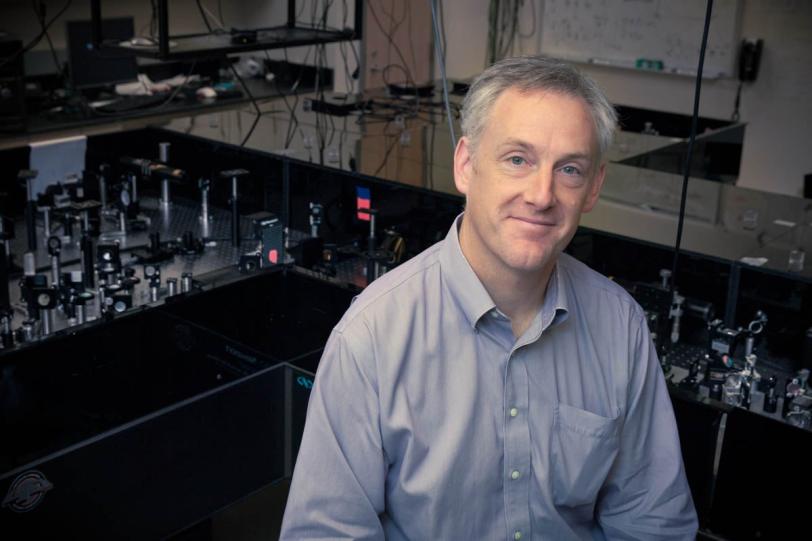

A Sense of Adventure and Intellectual Rigor Led PULSE Chemistry Professor Kelly Gaffney to a Successful Career in Science

By Mike Ross

Looking back at his childhood, SLAC’s Kelly Gaffney recalls the joys of exploring rocky Puget Sound beaches near his Seattle home and engaging in challenging, evidence-driven dinner-table discussions with his parents and older sister.

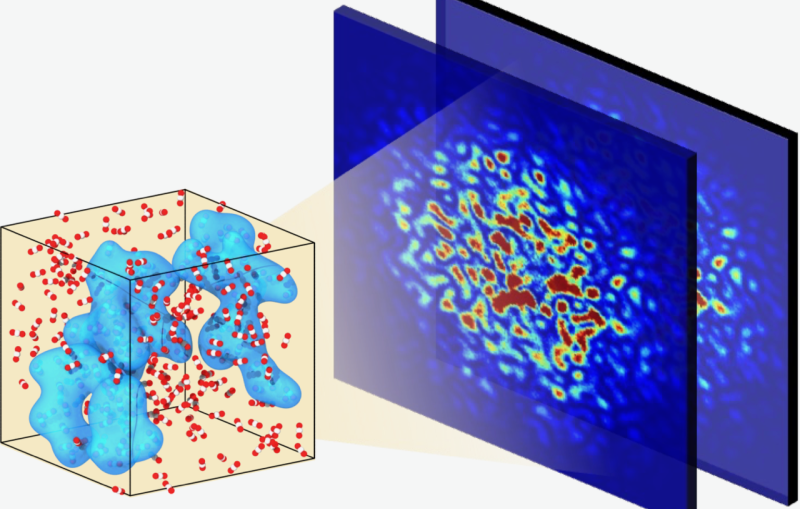

Now he’s enjoying similar explorations and thought-provoking debates as a chemist and associate professor at PULSE, a Stanford/SLAC joint institute for ultrafast energy science. He’s using the ultrashort, intense X-ray pulses from the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) to learn how molecules absorb and store energy and how chemical bonds are created and modified.

In recent years, Gaffney’s group has shown how hydrogen bonds switch between water molecules and resolved questions posed in the 1980s about how important catalysts respond to light and promote chemical reactions.

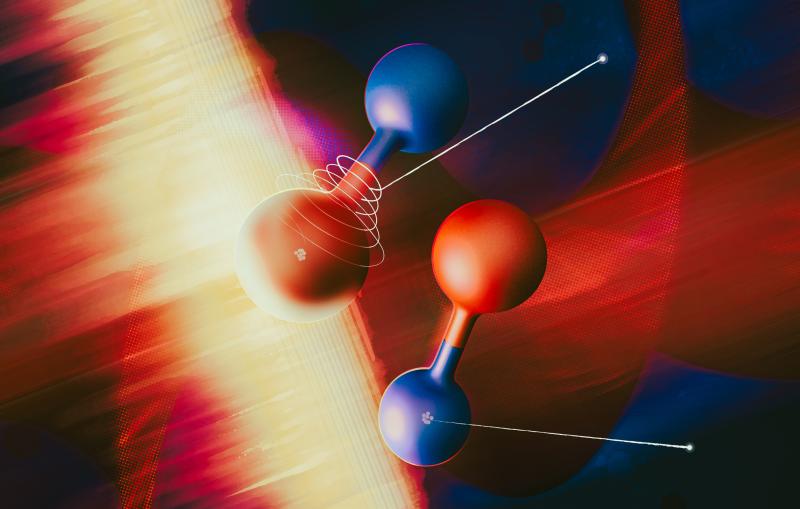

“A classic example is ruthenium,” Gaffney said. When light hits a ruthenium atom, the added energy stays with the atom for a relatively long time – long enough for many beneficial reactions to use that extra energy. This is called an "excited-state lifetime."

The problem with ruthenium is that it’s rare and expensive. But sitting just above ruthenium in the periodic table is iron – an extremely common and inexpensive material.

“We’d love to use iron instead of ruthenium in solar-energy catalysts,” Gaffney said. “That could enable a host of solar-driven chemical processes to become economical, which is a major goal of Department of Energy research.”

However, iron’s excited-state lifetime is more than 10 million times shorter than ruthenium's – not nearly long enough for many chemical reactions to occur.

“We’re trying to learn why there’s such a big difference and what we could do to increase iron’s lifetime,” Gaffney said. “LCLS is an ideal tool for this problem because its short, intense pulses can excite many atoms at once, allowing us to see their behavior more clearly.”

Chemistry wasn’t on his mind when he attended Evergreen State College, which shunned many standard education practices, such as grades, in its quest for multidisciplinary instruction. "In my sophomore year, I took the team-taught science course called 'Matter in Motion' and realized that I liked its chemistry sections,” Gaffney said. He was admitted to the University of California-Berkeley’s chemistry graduate school in 1995.

“Kelly had a terrific understanding of chemistry and physics,” said his adviser, Professor Charles Harris. “I was most impressed with his complete independence when he took over projects. He brought creativity and imagination to the problems he looked at – he was always thinking out of the box.”

At Berkeley, Gaffney learned how to use short ultraviolet light pulses to probe the formation of chemical bonds and the progress of chemical reactions, research that resulted in two papers in Science.

“What made chemistry interesting to me was that it's dynamic,” Gaffney said. “I wanted to learn how reactions changed things at the level of the atoms.”

After two years’ postdoctoral research at Stanford, Gaffney was hired in April 2003 by SLAC, which was creating new research teams in anticipation of LCLS’s operation. That August, he was chosen for a new assistant professor faculty position.

Before LCLS, Gaffney’s group did its first X-ray science experiments with David Reis, Phil Bucksbaum and Aaron Lindenberg at the Sub-Picosecond Pulse Source, located then at the end of the two-mile-long SLAC linear accelerator.

“Those experiments were a big part of my growth,” Gaffney said. “With X-rays, you can see directly where the atoms are and gain a deeper understanding of why molecules do what they do.”

Introducing Gaffney at a SLAC Colloquium last year, Uwe Bergmann, interim associate director for LCLS and a collaborator on some of Gaffney’s research, said, “Kelly is the type of scientist for which we built LCLS.” He adds, “Kelly is also one of the nicest, most thoughtful and most interesting people you will meet at SLAC.”

Since getting tenure last summer, Gaffney has been planning ways to expand his reach. “I'm hoping to help make the SLAC science results even better by mentoring younger scientists and staff, who have many good ideas,” he said.

Gaffney’s also initiated an effort to develop a lab-wide strategy and five-year roadmap for SLAC’s ultrafast chemical science research.

The new and important problems awaiting him seem as numerous and inviting as the pebbles on the Puget Sound beaches of his childhood.

“The joy of my job is that I get to learn for a living, pursuing my curiosity,” Gaffney said. “I haven't lost that.”

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, California, SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science.

The Stanford PULSE Institute is a joint institute of SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University. PULSE seeks to advance the frontiers of ultrafast science, with particular emphasis on research using SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS). For more information, please visit www.stanford.edu/group/pulse_institute.

SLAC’s LCLS is the world’s most powerful X-ray free-electron laser. A DOE Office of Science national user facility, its highly focused beam shines a billion times brighter than previous X-ray sources to shed light on fundamental processes of chemistry, materials and energy science, technology and life itself. For more information, visit lcls.slac.stanford.edu.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.