X-ray Laser Maps Important Drug Target

Researchers have used one of the brightest X-ray sources on the planet to map the 3-D structure of an important cellular gatekeeper known as a G protein-coupled receptor, or GPCR, in a more natural state than possible before.

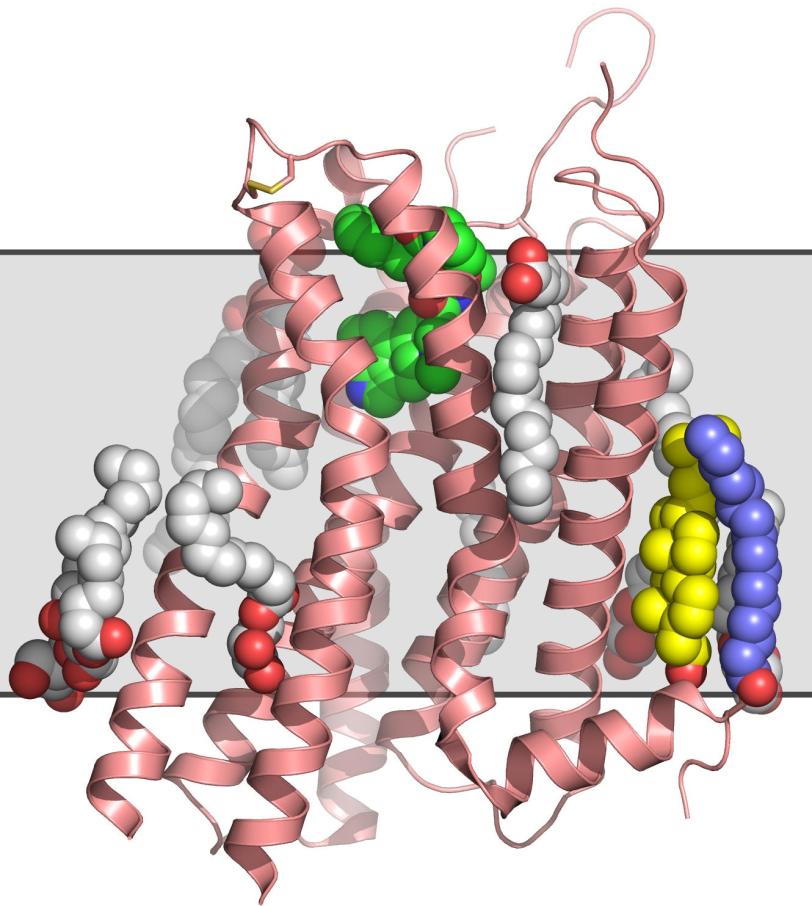

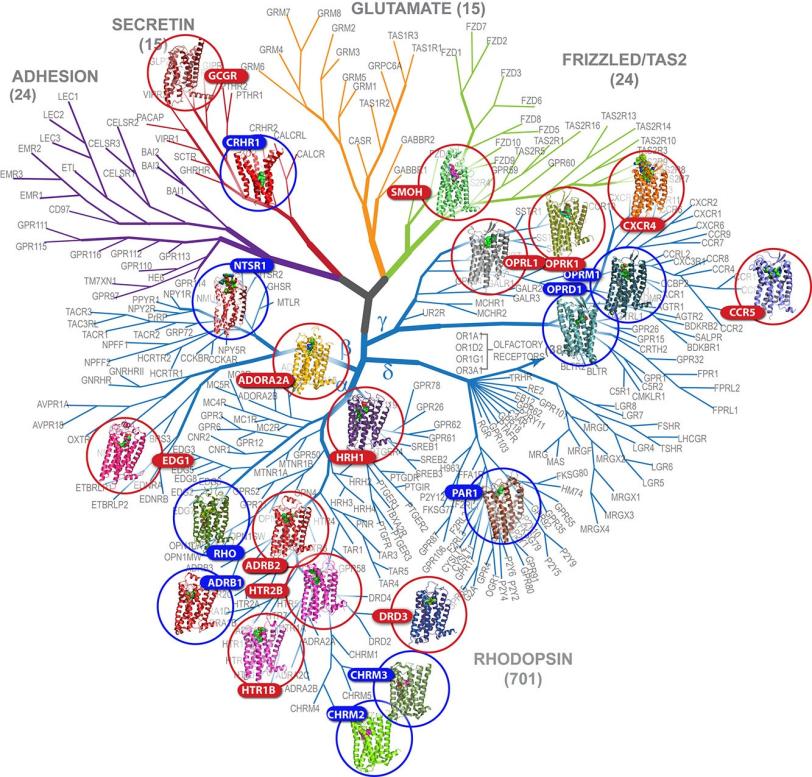

Menlo Park, Calif. — Researchers have used one of the brightest X-ray sources on the planet to map the 3-D structure of an important cellular gatekeeper known as a G protein-coupled receptor, or GPCR, in a more natural state than possible before. The new technique is a major advance in exploring GPCRs, a vast, hard-to-study family of proteins that plays a key role in human health and is targeted by an estimated 40 percent of modern medicines.

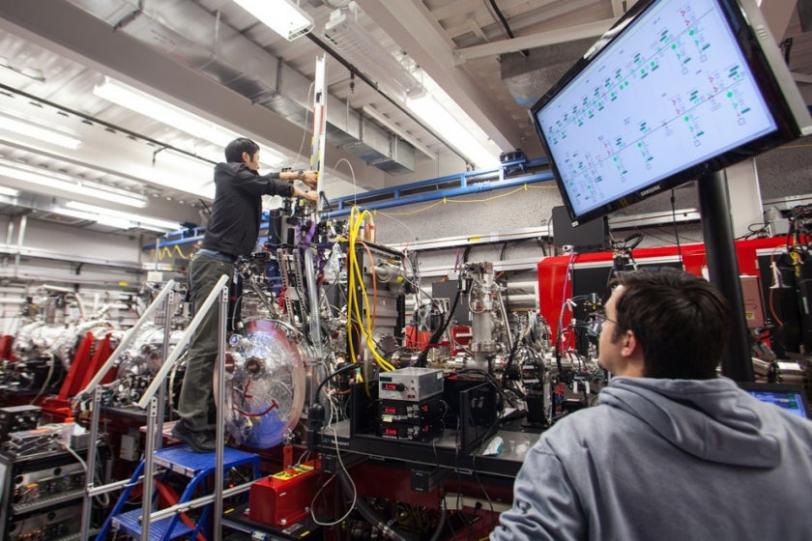

The research, performed at the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray laser at the Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is also a leap forward for structural biology experiments at LCLS, which has opened up many new avenues for exploring the molecular world since its launch in 2009.

“For the first time we have a room-temperature, high-resolution structure of one of the most difficult to study but medically important families of membrane proteins,” said Vadim Cherezov, a pioneer in GPCR research at The Scripps Research Institute who led the experiment. “And we have validated this new method so that it can be confidently used for solving new structures.”

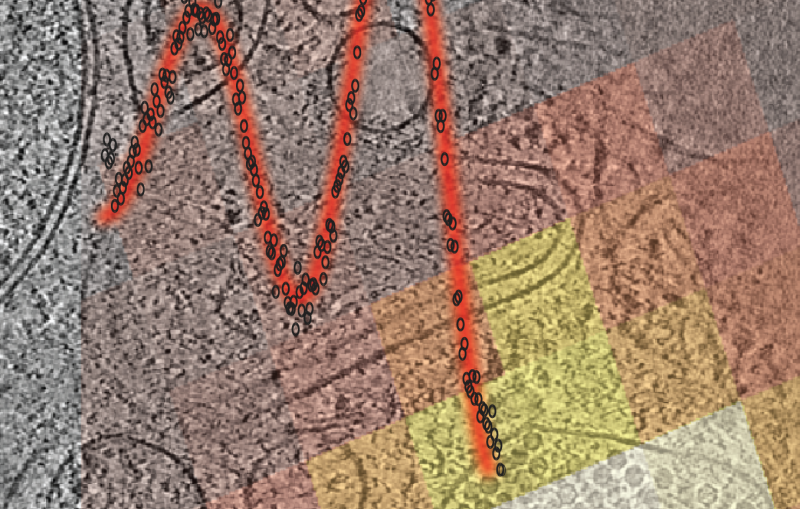

In the experiment, published in the Dec. 20 issue of Science, researchers examined the human serotonin receptor, which plays a role in learning, mood and sleep and is the target of drugs that combat obesity, depression and migraines. The scientists prepared crystallized samples of the receptor in a fatty gel that mimics its environment in the cell. With a newly designed injection system, they streamed the gel into the path of the LCLS X-ray pulses, which hit the crystals and produced patterns used to reconstruct a high-resolution, 3-D model of the receptor.

The method eliminates one of the biggest hurdles in the study of GPCRs: They are notoriously difficult to crystallize in the large sizes needed for conventional X-ray studies at synchrotrons. Because LCLS is millions of times brighter than the most powerful synchrotrons and produces ultrafast snapshots, it allows researchers to use tiny crystals and collect data in the instant before any damage sets in. As a bonus, the samples do not have to be frozen to protect them from X-ray damage, and can be examined in a more natural state.

“This is one of the niches that LCLS is perfect for,” said SLAC Staff Scientist Sébastien Boutet, a co-author of the report. “With really challenging proteins like this you often need years to develop crystals that are large enough to study at synchrotron X-ray facilities.”

Celebrating Crystallography - An animated adventure

Cherezov said that even after samples of a GPCR are crystallized and imaged, it can take several months to optimize the crystal size and collect enough synchrotron X-ray data to produce structural information. This study demonstrates that an LCLS experiment using smaller crystals can potentially condense that timeline to a matter of days.

Disorders linked to GPCRs include hypertension, asthma, schizophrenia and Parkinson's disease. Because of their vital role in regulating cells' signaling and response mechanisms and their importance to human health, advances in receptor-related research garnered the 2012 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

So far, scientists have been able to map the structures of fewer than two dozen of the estimated 800 GPCRs in humans. Although the human serotonin structure had been determined earlier with conventional methods, that effort took much longer and showed the receptor in a less realistic environment. The more accurate the structure, the better scientists can use it to tailor effective drug treatments without side effects. Thus, this new technology could eventually lead to an efficient platform for designing drugs based on GPCR structures.

“I view these recent experiments as just the beginning,” Cherezov said, “Now it is time to start making a serious impact on the field of structural biology of G protein-coupled receptors and other challenging membrane proteins and complexes. The pace of structural studies in this field is breathtaking, and there is still a lot unknown.”

The team has also studied two other GPCRs and a membrane enzyme at LCLS and is returning for follow-up research in January.

Additional contributors included researchers from SLAC; the Center for Free Electron Laser Science, University of Hamburg and Center for Ultrafast Imaging in Germany; Arizona State University; Trinity College in Ireland; and Uppsala University in Sweden. The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health Common Fund in Structural Biology, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and the National Science Foundation, with additional support from the Helmholz Association, the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, and Science Foundation Ireland.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, California, SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science. To learn more, please visit www.slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC's LCLS is the world's most powerful X-ray free-electron laser. A DOE Office of Science national user facility, its highly focused beam shines a billion times brighter than previous X-ray sources to shed light on fundamental processes of chemistry, materials and energy science, technology and life itself. For more information, visit lcls.slac.stanford.edu.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Citation

Wei Liu, et al., Science, 20 December 2013 (10.1126/science.1244142).

Press Office Contact

Angela Anderson, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory: angelaa@slac.stanford.edu, (650) 926-3505.

Scientist Contacts

Vadim Cherezov, The Scripps Research Institute: vcherezo@scripps.edu, (858) 784-7307 or (857) 353-5584.

Sébastien Boutet, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory: sboutet@slac.stanford.edu.